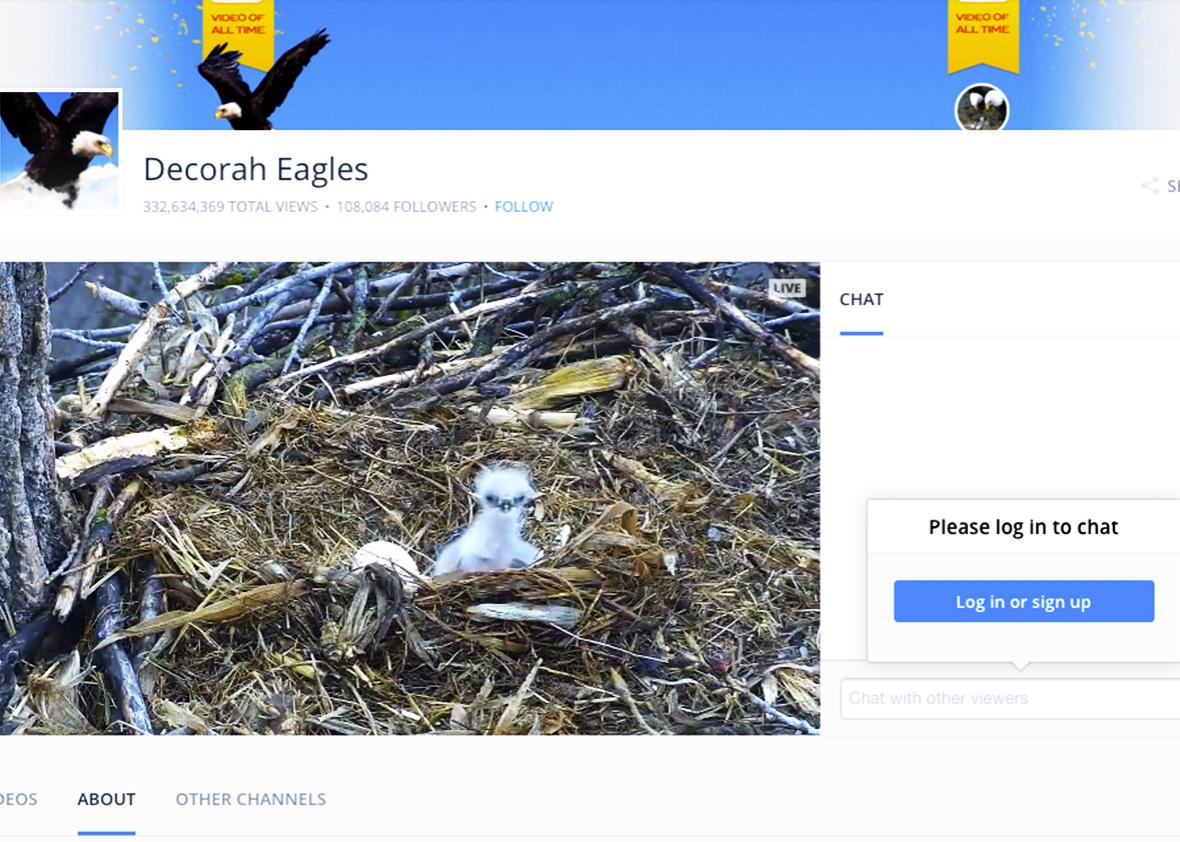

There are three main topics of conversation you can have with my grandfather: 1) college sports, 2) Iowa weather, and 3) the Decorah Eagles.

The Decorah Eagles, a bald-eagle pair and their offspring who nest in Decorah, Iowa, every spring and summer, became an Internet phenomenon in 2011. That year more than 200 million people tuned in to live-stream footage of the eagles raising their eaglets from eggs to young adults. Since the cam’s 2007 installation, the birds have become a pop culture sensation. PBS featured them in a 2008 Nature documentary, “American Eagle,” and the eagles were the focus of Wired Science’s most popular post of 2011, which received so much traffic the website crashed. The Decorah Eagles have even inspired a question on Jeopardy! in the category “webcams.”

Grandpa Harry didn’t jump on the bandwagon until 2014, but since then he’s mentioned the eagles in approximately 90 percent of our conversations. It was less than a week after he started tuning in (daily!) that he started to keep detailed notes on behavior, eaglet growth, and of course, the weather. Grandpa has long had a fascination with birds, and with nature in general. He maintains an urban garden in a nearby plot, and he owns an impressive collection of nature guides and bird feeders. At 83 years old, it’s increasingly difficult for him to enjoy a walk in the woods, hunting mushrooms and bird watching. The Decorah Eagles cam brings a welcome wilderness experience, right into his cozy computer room.

But can webcams and other technologies threaten the traditional, pristine wilderness experience? In the March 13 edition of the New York Times Sunday Review, writer and outdoor enthusiast Daniel Duane critiqued the world of conservation technology. Species preservation has become a tech-heavy business, complete with GPS, radio collars, DNA sequencing, and even drones. But, Duane wonders, “if technology helps us save the wilderness, will the wilderness still be wild?” He argues that using technology to protect species leads to the hubristic belief that humans possess all the know-how needed to manipulate and even build ecosystems. And part of being wild is remaining unmanipulated. Duane laments the loss of untouched landscapes: “The best strategy is still just to avoid destroying habitat in the first place, and sometimes to let developed places become wild again.”

Duane’s concerns are not unusual. In 2014, the director of the National Park Service, Jonathan Jarvis, banned drones from national parks, in large part to prevent potential wildlife disturbance. That’s reasonable: Drones can pose annoyance and even danger to animals. A University of Minnesota research team found that bears become stressed in the presence of drones, with heart rates spiking upon encounters. Apparently more than annoyed, some birds actually attack drones. Thus far it seems the drones tend to lose in bird vs. drone matches, but the Audubon Society reports that as drones becomes more common and more robust, future encounters could yield injury to birds who boldly confront unmanned aircraft.

But if deployed thoughtfully, technology doesn’t have to alter nature in destructive ways. Nor does tech necessarily have to interfere with the human experience of nature; it can enhance it and even protect it.

Duane highlighted the uses of technology to save endangered species within parks. Though he is wistful for the sight of a bighorn sheep sans radio tag, he admits, “surveillance and manipulation of the wild sure beats doing nothing, especially when technology can make conservation easier.” In addition to bolstering efforts to preserve individual species in protected areas, technology is also being used to save the parks themselves by keeping them relevant to a new generation of stewards and explorers. The National Park Service is struggling to attract millennials, as Jarvis mentioned in a speech celebrating the park services’ centennial this year. Certain technologies can help the park service reach out to the younger population they are desperate to attract. Live-stream cams, for example, can be used in educational and promotional materials distributed to schools, allowing students to observe wild animals in real-time, real-life environments. And Instagram and Twitter accounts linked to the live-stream cams via hashtags help parks appeal to potential visitors who are social-media–savvy.

For instance, Katmai National Park in Alaska has partnered with Explore, a nonprofit organization specializing in wildlife photography and filming, to launch a live-stream of brown bears fishing and swimming in the Brooks River. Nature enthusiasts can observe one of the park’s most popular species and tweet about their experience using the hashtag #bearcam. The nation’s original national park, Yellowstone, also hosts a series of webcams that provide live-stream footage of the park’s most popular spots, including Mammoth Hot Springs, Mount Washburn, and Old Faithful.

Recently, the park service established a WebRangers program, another way for children to experience the parks in their homes and classrooms. On the website, students can build a customized ranger station and hike the virtual trails on electronic field trips. The program is intended to invite and inspire online explorers to become outdoors explorers in the national parks.

Though the park service as a whole is having trouble attracting younger visitors, the more internationally popular parks like the Grand Canyon are experiencing overvisitation, the “loving our parks to death” scenario. NPR reports that more than 305 million people visited the parks last year. Of course, I was one of those 305 million people, and I find it encouraging to see surging interest in our nation’s premier protected lands. But it is undeniable that more people bring more cars, more trash, and more noise.

In the past, the park service has tried to counter the negative effects of high visitation with the development of visitor facilities, roads, and trails. Such development is a “necessary evil” that contains human impacts and forms a buffer between humans and the landscapes. But considering the limited space and funds in the national parks, there should be a cap to increasing development within them. Webcams and other online tools present an opportunity to set a buffer between humans and the wild without the space and money required to construct roads, fences, and restrooms.

When used in combination with visitor restrictions on particular areas of the parks, webcams can allow the overflowing number of nature enthusiasts to witness the wild without disturbing the wild. For example, webcams at Yosemite National Park offer visitors access to Half Dome, Yosemite Falls, and El Capitan, without leaving any footprints on the Yosemite Valley floor. The Grand Canyon could follow suit. I admit that few tourists would allow a webcam to entirely replace travel to a world-renowned “bucket-list” destination. But the park can at least restrict overvisitation to developed locations in the park (the South Rim), while live-stream webcams display areas of limited public access. Grand Canyon National Park already restricts entry into backcountry zones. Why not open those areas up to live-stream viewing, increasing educational opportunities and inspiring environmental stewardship in people unable to obtain a permit (or those sitting on the waiting list)?

The trick is ensuring that online tools are seen as portals to the park. A younger me would have felt that live-streaming was a cheap tech trick that could never replace the full experience of the wild—which requires facing one’s fears, challenging survival skills, and encountering the sublime beauty (and ugly reality) of nature.

But live-stream broadcasts can be breathtaking. I have watched webcams installed in locations that I have traveled to, from Costa Rica to California. I still get shivers of exhilaration watching a shark approach me via webcam, though it is much easier to recover from the adrenaline rush when I know he is swimming more than 2,000 miles from me and my laptop.

The Internet connection should be the entry point, not the endgame. Webcams cannot replace the wild, but they can enhance our experience of it. Few people can escape to nature on a regular basis, whether because they’re far away or because they have limited mobility. Sitting at home on a rainy day watching the Decorah Eagles with my grandfather sure beats an episode of reality TV. And when we tune in, we feel inspired, awakened to beauty and complexity of an eagle’s life. Grandpa Harry’s passion for eagles has grown beyond the computer room. He relishes moments in which he gets to teach his grandchildren about eagles. And on a clear, sunny day, when he’s feeling well, Grandpa Harry never misses an opportunity to head down to the riverbank to see the wild eagles with his own two eyes, no webcam necessary.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.