Every industry has a few bad eggs. For the egg industry, it was DeCoster Egg Farms. In 2010, DeCoster was harboring foul cages full of sick hens. Those hens laid 550 million eggs tainted with a toxic strain of Salmonella enteritidis, which in turn ended up on grocery store shelves. The eggs were broken into skillets, whisked into mayonnaise, and ended up sickening as many as 6,200 Americans in what would become the largest egg recall in U.S. history. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration quickly passed laws to reform egg safety—but not before consumers had seen the crack in the industry’s veneer.

Eggs vex us. They’re touted as the pinnacle of nourishment, the best friend of the paleo practitioner, and the centerpiece of the classic American breakfast. “Eggs are nature’s form of portion control … an all-natural, high-quality protein powerhouse,” says the Egg Nutrition Center, an entity run by the American Egg Board. At the same time, news reports tell of deadly salmonella outbreaks and egg recalls. Plus, in the post-Pollan era, buying a carton of eggs means wrestling with questions of chicken cruelty.

So what’s an omelet-loving yuppie to do?

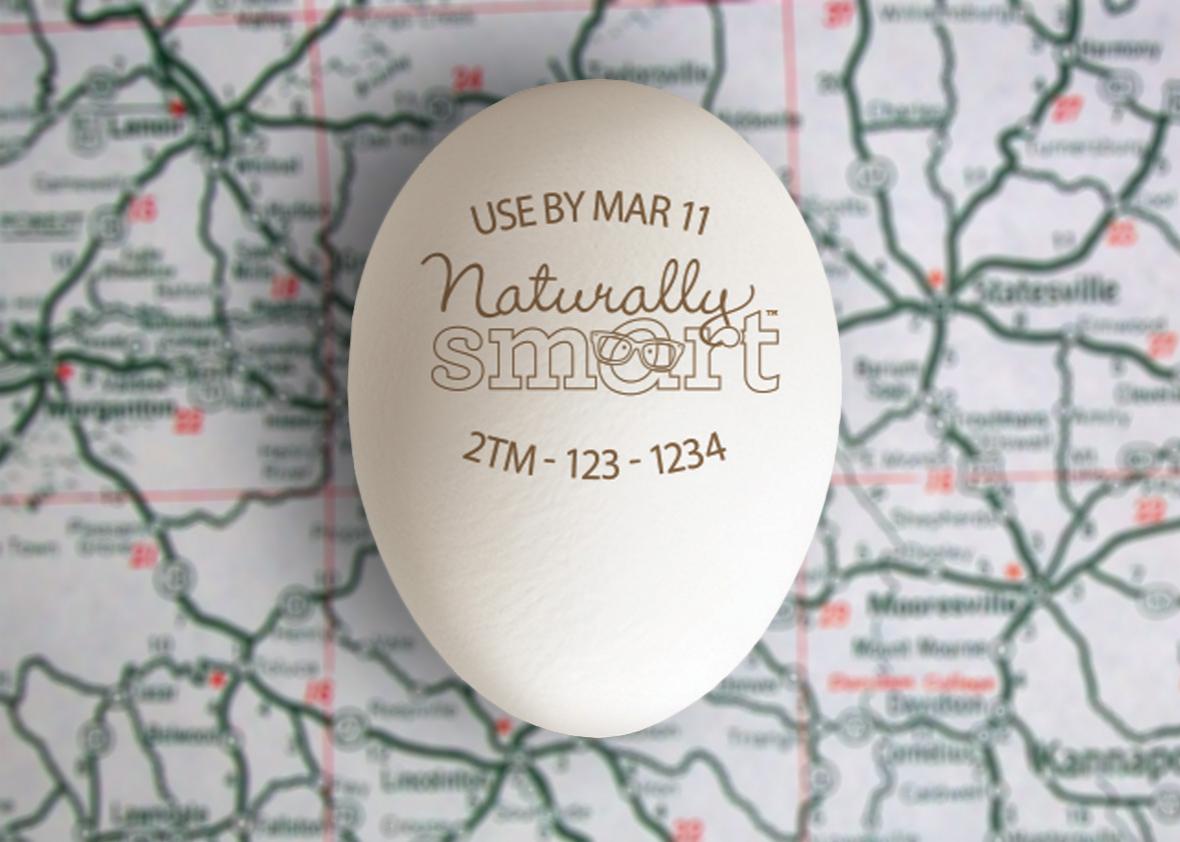

Enter TEN Ag Tech, a Southern California–based startup that aims to take the existential crisis out of your egg purchase. The tech company seeks to keep the egg industry accountable in two ways. First, it offers mobile-based apps that increase transparency on farms by monitoring human behavior—i.e., keeping track of who enters and leaves a hen house. Second, it engraves each individual egg with its own (nontoxic, naturally) gold laser barcode. Input that barcode onto the Naturally Smart Egg website, and you’ll instantly know everything about that egg’s origins: the breed of hen that laid it, the production method that spawned it (cage-free, traditional caged production, or free-range), and the moment it was packed within 180 seconds.

TEN Ag Tech

If this is all beginning to sound like a certain Portlandia skit—you know, that one where the couple interrogate their waitress about Colin, the chicken they will be enjoying—then you’re on the right track. It’s that, plus data. TEN Ag Tech seeks to “reconnect consumers to the farms that feed them,” according to its website. Since last July, consumers have been buying the company’s Naturally Smart eggs on the shelves of Chicago’s high-end Mariano’s grocery stores, a division of Kroger.

TEN Ag Tech’s vision is not limited to eggs: In February, the company will debut its traceable technology for coffee and meat. The goal is to prevent foodborne illness debacles like the recent outbreaks at fast-casual chain Chipotle. “As monoculture grows, companies like Chipotle are creating alternative realities, fresh food, local foods coming from local places,” says Jonathan Phillips, the company’s president and CEO. “The question is: When you’re dealing with 40,000 farms, how on Earth do you ensure that they’re all producing food for you safely? Our tech begins to solve that problem.”

Well, maybe. Trace-back technology does offer some concrete benefits. In our industrialized food system, fresh food travels thousands of miles, switching hands myriad times before making it onto your plate. When foodborne illness strikes, it can take about 30 days for the FDA to trace an egg back to its source, and 45 to 60 days for other foods, says Kevin Keener, a food scientist who focuses on egg safety at Iowa State University. By the time the trace-back is done, that outbreak could have spread to a different state or dissipated entirely—rendering a USDA announcement of little good to the public. “If traceability goes back to farm and links it to certain egg, that would facilitate a much more rapid response,” says Keener, who works with the American Egg Board.

But when it comes to helping us avoid outbreaks in the first place, this kind of data may be useless, says Ken Anderson, a poultry-extension specialist at North Carolina State University who focuses on egg processing, production, and safety. That’s because in most cases, contamination takes place after the production process, whether in a grocery store, a restaurant, or in your own kitchen. “It’s workers at a grocery store. It’s consumers opening up the egg cartons. It’s people transferring eggs to plastic cartons in their fridge,” says Anderson. “Those little things all add up and add a potential for contamination totally separate from how the eggs were produced.”

Ultimately, a product like TEN Ag Tech’s may be less about food safety than consumer fears. The trace-back technology, which Phillips says was directly inspired by the Great Egg Scare of 2010, appeals to lingering concerns around eggs and foodborne illness. The company’s promotional video asks: “What happens when this system is compromised? How do you ensure you won’t be affected? How do you keep your family safe?” This is followed by the foreboding: “Remember 2010?” From the company’s perspective, this is a smart strategy. Media hype has people terrified of foodborne illness, and individuals and businesses will both do a lot to avoid it—including shell out cash. While Naturally Smart eggs currently sell at Mariano’s at the same price as regular ones—around $1.89 per dozen—Phillips imagines them ultimately selling for about 40 cents more per dozen.

But from the consumer’s perspective, fear always a bad place from which to make rational decisions. The 2010 outbreak was horrifying, but it was an anomaly: Massive salmonella outbreaks from eggs are exceedingly rare, writes Slate’s L.V. Anderson. According to the USDA, in total, about 1 out of every 20,000 eggs is infected, which means that the average person will consume a single contaminated egg in a 78-year lifetime. Eggs cause far fewer illnesses than meat, seafood, dairy, or fruits and vegetables. You shouldn’t have to worry, as long as you handle your eggs properly: That is, cooking them at 160 degrees Fahrenheit (which instantly kills all salmonella bacteria), and keeping them refrigerated up until that point (which makes bacteria easier to kill).

Given those odds, something like TEN Ag Tech is an “overreaction,” says Ken Anderson. “Today, I believe that eggs are as safe or safer than anything you can buy at the grocery store,” says Anderson, who has received funding from the American Egg Board, USDA, FDA, and industry.

Yes, the risk is small. But it’s there. Americans eat a lot of eggs—about 250 per person per year. And, to poach a phrase from sex education, the only way to avoid all risk is to abstain completely. (If you want to do that, your options are better than ever; consider eggless mayonnaise product Just Mayo or vegan egg-yolk replacement the Vegg.) TEN Ag Tech relies on the premise that, if only we had enough data, we could live a life with zero risk. Sorry to break it to you, but that’s fantasy. People will always get sick. Cracks will lurk in the system. “The best of practices will never give you a guarantee,” says Keener. “For any food you can never get to zero. You can only reduce risk.”

But there’s still one population that could certainly benefit from TEN Ag Tech: animals. Today’s consumers want more than food that won’t kill them. They’re rightfully bothered to think of “hens who spend their lives with six or seven others in cages the size of an open newspaper, their droppings carried away by one conveyer belt while the eggs are whisked off by another,” as the New York Times put it. “The challenge reflects a strange mix of consumer nostalgia and entitlement,” Jennifer Chaussee wrote in a smart piece for Wired. “We want it all—eggs raised humanely at scale—and at a price we can still afford.”

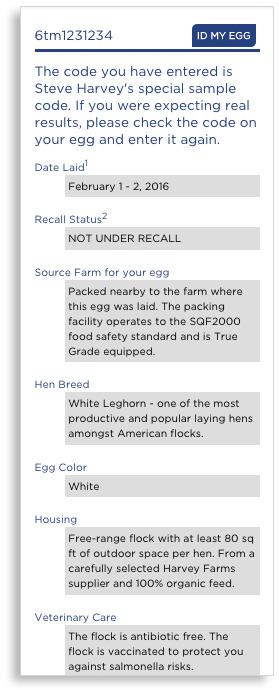

Under pressure from consumer demands, big companies like McDonald’s are embracing the cage-free egg—but the tough part is keeping them accountable. After all, who is to say that the eggs in your cage-free carton are actually cage-free? Like “organic,” the definitions for the term “cage-free” run the gamut—and you can bet that some companies will take advantage of the imprecision. Ag Tech can help (assuming consumers can get their hands on an egg to check the source). From a sample egg ID on its website: “Free-range flock with at least 80 sq ft of outdoor space per hen … 100% organic feed … The flock is antibiotic free.”

So yes, if you care about Colin’s well-being and are willing to pay the extra price, individual egg sourcing may be for you. But if you’re looking for a guarantee that the raw eggs in your cookie dough won’t poison you, you’re probably in the wrong aisle.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, follow us on Twitter and sign up for our weekly newsletter.