The Internet has always been weird. It’s weird because it encourages us to pursue increasingly fragmentary slivers of experience, and weirder still because it allows us to share those shavings with others like us. In this regard, at least, 2015 may not have been unusual, but it was still thick with a surreal slurry all its own. This was, after all, the year when Jon Hendren, a Twitter personality who goes by the handle @fart, trolled an HLN interviewer by responding to questions about Edward Snowden as if he’d been asked about Edward Scissorhands instead. And that wasn’t even the silliest Snowden-specific prank of the season.

Because the weirdness of the weird Internet is mostly environmental, trying to list its greatest hits in order, or even to list them at all, would mostly miss the point. As Hendren’s jape demonstrates, the weirdness of the Internet often has more to do with actively making things strange than it does with the mere fact of strangeness—not just weird, but weirding. What follows, then, is a non-chronological list of (some of) the weird Internet’s best moments of the year, an attempt to make sense of why they worked without undoing what made them great.

That approach is necessary in part because the Internet’s oddities often linger: Despite the inherent peculiarity of the Web, we sometimes go out of our way to make it more peculiar, as did those of us who installed a Chrome extension that changes every appearance of the word millennial on a page to snake person, enlivening even the dullest articles with a grace note of the bizarre. Changing millennials to snake people calls attention to the strange (and fetishistic) language the old(er) use to discuss the young. Ultimately, then, its real function may be to point out the weirdness of what we’re already doing. Here at Slate, we attempted something similar after Google made the terrible decision to rename itself Alphabet. Pushing back against what Lowen Liu called a “semiotic land grab,” we released a Chrome extension of our own that changes the word alphabet to Google, whether or not it refers to the company.

Just as Chrome extensions can serve critical functions, the Internet’s best weird inventions are often interventions, serving particular ends, not just peculiar ones. In November, when Belgian authorities placed Brussels on lockdown, they requested that citizens refrain from tweeting about police activities, lest they disrupt counterterrorism efforts. Civilians did their part by posting a steady stream of cat pictures instead, seeking to baffle any who might seek to gather information from the social media site.

Such collective activities speak to the communal quality of almost all weird Internet phenomena, which work best when they play out for audiences that involve themselves in the unfolding. This may be why parody podcasts such as Hello From the Magic Tavern work so well. Podcasts generate an illusion of friendly intimacy by allowing their audiences to cultivate a regular—and frequently banal—familiarity with the grain of their hosts’ voices. Magic Tavern, which premiered in March, achieves something similar by presenting itself as an ordinary panel conversation podcast (not unlike a few you might listen to) that just happens to take place in a magical kingdom called Foon. Pokerfaced in its commitment to genre conventions, and madcap in its world building, it manages to involve listeners in the lives of its characters, despite the profound goofiness of everything that comes out of their mouths.

Nothing, however, exemplifies the collective character of the Internet’s weirdness better than Reddit’s countless “subreddit” communities. The ideal representation of the site’s inclination to the strange arrived this year in the form of the button. Announced on April 1, the button both was and was not a joke: A clock counting down from 60, it reset itself every time a registered user pressed it, but no user was allowed to press it more than once. In the months after its initial release, countless subcommunities sprung up around the button, sects of those who had activated it at specific times, as well as those who refused to press it at all. Those who participated—and they were many—were both silly and serious, weaving bizarre explanatory myths in the absence of official information.

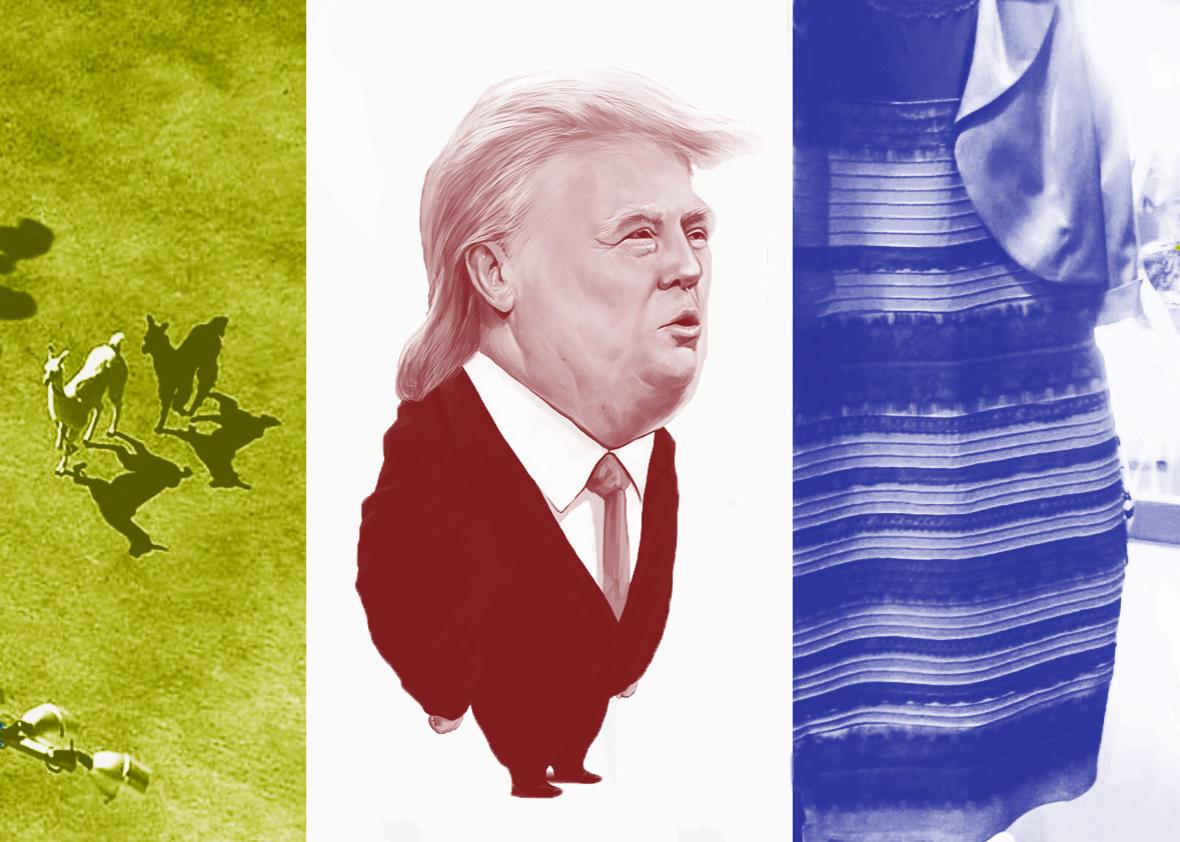

In late February, a different—and differently weird—phenomenon also showed how disagreement can bring the entire Internet together, a dress that some saw as blue-and-black and others as white-and-gold. In Slate, Amanda Hess described it as “the perfect meme,” and it was, partly because it was so simple that it couldn’t “degrade or mutate as it jumped between platforms and social networks.” For most, its central mystery was as inexplicable as its near-universal popularity, and that may have been the secret to its charm. We couldn’t agree about its color, and some weren’t sure whether this was the sort of thing responsible news outlets should be covering, but everyone seemed to be invested asking these questions.

This may be the paradox of Internet weirdness, that the greatest oddball outliers sometimes bring us together best. Just before the dress took over the Web, two escaped llamas briefly captivated countless eyeballs as they galloped through the streets of Sun City, Arizona. The stakes couldn’t have been lower, and that’s what made it essential watching. For a few short, delightful hours, we were able to collectively pretend that these errant camelids mattered to us, and in so doing were able to temporarily lessen the burdens that really mattered, joyfully neglecting all those things that weighed on us more individually.

There are, however, instances of Internet weirdness that create burdens of their own, often because they’re so damn creepy. Just in time for Halloween, Slate’s Lily Hay Newman wrote up an enigmatic and haunting video that had been making the rounds. While I can’t vouch for your safety if you watch it, you should absolutely read her article, in which she explores some of the efforts Internet users (especially on Reddit—surprise!) have put into making sense of it. Here again, the very act of grappling with strangeness is itself strange. Who would want anyone to dwell on something this eerie?

In review, 2015 shows that weirdness is both a coping mechanism and the condition with which we’re coping. Naturally, it’s the year’s avatar, walking comb-over Donald Trump, who demonstrates this best. Much as it’s often difficult to tell whether the weird Internet’s greatest creations are put-ons, it’s impossible to discern whether Trump takes himself seriously. That may be why the best responses to his ongoing candidacy—like this awesomely amateurish attack ad—simultaneously are and are not jokes. In Trump’s squinting eyes, we glimpse both our reflection and our fate: Only the weird can save us from the weird.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.