To the extent that they cross our minds at all, we generally think of patents as good things: rewards for meritorious inventors. It might seem, then, that stronger patents would lead only to good things for inventors and for society overall. Indeed, many of those debating patent reform in Congress take that very tack to the issue.

But too much of a good thing isn’t always better, as anyone who has ever had an ice cream headache can attest. Patent rights, when too strong, can be a liability rather than an asset.

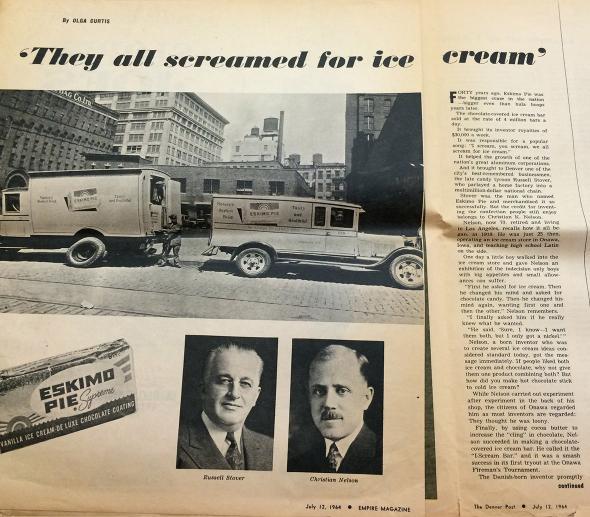

The history of the Eskimo Pie is a classic tale of American innovation, of an enterprising young inventor who built a national company out of a hometown confectionery. But it is also the story of a too-expansive patent that would drag down that national company along with an entire industry. It is that less-known story, which I have reconstructed from court decisions and corporate record archives, that should inform modern debates over patent reform.

* * *

The creator of the Eskimo Pie was a World War I veteran, high school teacher, and ice cream store owner named Christian Kent Nelson. As Nelson himself told the story to the Denver Post’s Empire Magazine: Around 1920, a young boy walked into his store and couldn’t decide between getting an ice cream and getting a chocolate bar. Nelson wondered whether he could give that boy both the chocolate and the ice cream in one product and set out to make an ice cream bar coated in chocolate. Apparently this was a difficult proposition, and he spent weeks trying to find a formula for sticking chocolate to ice cream.

Finally, after consulting with one of his store’s suppliers, he learned that chocolate candy makers would add cocoa butter to the chocolate coating. Nelson tried this technique with his ice cream bars, and by the fall of 1920 he had the perfect recipe for chocolate-coated ice cream bars. He sold out a batch of 300 “I-Scream Bars” in a local test at a firemen’s tournament. Convinced that his product could make it big, Nelson sought out a business partner to bring his idea to a national market. On July 13, 1921, Nelson found that business partner in a then-unknown young entrepreneur named Russell Stover.

The ice cream bar, now renamed the Eskimo Pie, was an instant success. Newspapers (perhaps exaggerating) called Nelson a millionaire and reported that he was making royalties of $30,000 a week. In 1925, the song “I Scream, You Scream, We All Scream for Ice Cream” glorified the novelty confection. Nelson and the Eskimo Pie were well on their way to success and fame.

And that’s where the patent got in the way.

* * *

Soon after he devised the perfect formula for chocolate-covered ice cream bars, Christian Nelson applied for a patent. He was thus obtaining patents for exactly the reason that patents are meant to serve: to protect inventors who put in hard work and research to create something new and useful. That protection is a right to exclude competitors from making, using, or selling the invention. But there was a problem. The Eskimo Pie patent described an invention altogether different from what Nelson had actually invented.

A patent’s exclusive right can be drawn narrowly to cover only a specific invention. Or it can be drawn broadly, to block a wide range of products sharing certain basic features. A broad patent is obviously more valuable to the owner. But a patent cannot be so broad as to cover old ideas, those in the “prior art” to use patent law terminology. It would make little sense, after all, to grant someone the powerful exclusionary patent right on an idea already known to the world.

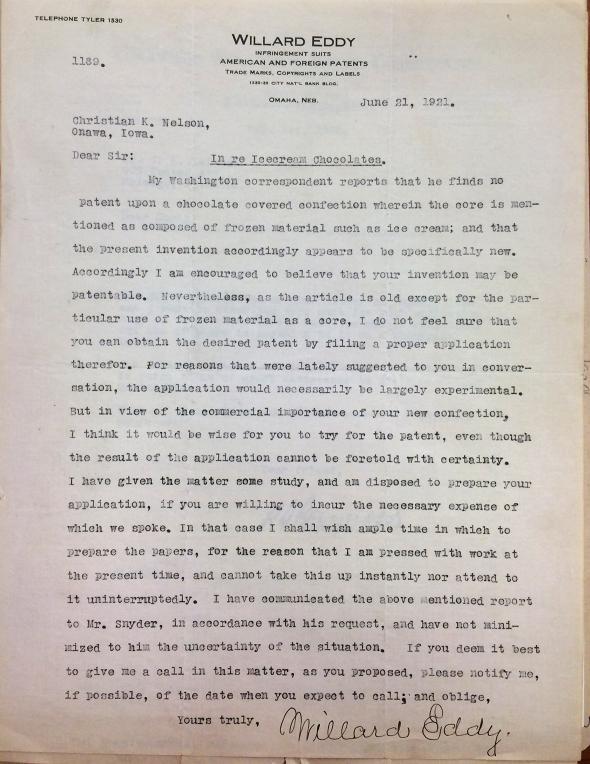

In the case of the Eskimo Pie, patent breadth would be the central problem. From the start, it was unclear whether a patent could be obtained at all, as one attorney explained to Nelson in a letter:

[A]s the article is old except for the particular use of frozen material as a core, I do not feel sure that you can obtain the desired patent by filing a proper application therefor. For reasons that were lately suggested to you in conversation, the application would necessarily be largely experimental.

Letter from the patent attorney to Christian Nelson, June 21, 1921.

Image via Public Domain

Nelson went ahead and applied for the patent anyway, and on Jan. 24, 1922, he was issued U.S. Patent No. 1,404,539.

The difficulty of making the Eskimo Pie lay in the formula for the chocolate coating. So one would imagine that the patent would have described precise specifications for making that coating. Precise ratios of cocoa butter to chocolate, temperatures for heating and cooling, or the number of seconds to dip, for example.

The patent contains none of that. Running a scant page and a half of text, the patent merely describes “a core consisting of a block or brick of ice cream, of general rectangular configuration,” that is “sealed within a shell … of edible material which may be like that employed in coating chocolate candies, although preferably modified to harden at a lower temperature.” There is no description of how the coating’s composition or how it is to be “modified.”

Instead, the patent focuses on features that seem irrelevant or tangential to the actual inventive discovery. The “claims” of the patent are supposed to identify an invention’s key features. But instead the Eskimo Pie patent identifies embarrassingly obvious features: “normally liquid material frozen to a substantially solid state” (i.e., ice cream), an “edible, sustaining and form retaining casing” (i.e., hard chocolate), and a “bar-like contour” (i.e., shaped like a rectangle).

The patent was not intended to protect Nelson’s actual discovery of a formula to make a chocolate coating that can work with ice cream. Instead, it appears the patent was intended to monopolize the entire market of coated ice cream bars. Indeed, according to an internal report by the company, the Eskimo Pie offices apparently celebrated on the day that the patent issued because it was such a “broad and basic patent, covering not only the chocolate-covered ice cream bar, but almost every conceivable variation of it.”

The expansive quality of the Eskimo Pie patent is strongly reminiscent of many of the problematic patents in force today. There are plenty of recent stories of patents on calorie-counting meal planning, showing advertisements before videos, and playing card games over the Internet. The Electronic Frontier Foundation maintains a whole list of these too-broad patents on basic ideas.

An ongoing patent case illustrates perfectly the alignment between 1920s Eskimo Pies and modern software. In McRo Inc. v. Bandai Namco Games America, an animator named Maury Rosenfeld developed an advanced technology for synchronizing lip movements of animated characters. Major animation studios called the software “revolutionary.” But Rosenfeld’s patent, which was filed in 2001, doesn’t cover the specific algorithms or parameters behind the technology. Rather, as I read them, the claims of the patent describe a generic process of 1) receiving some unspecified rules about how to animate lips, 2) receiving data about the words spoken, 3) applying the rules and some unspecified mathematical formula to that data, and 4) using the output of the formula to animate characters. Other than being specific to animated lip synchronization, this patent claim essentially boils down to “receive data, process it, and use the results.” That is basically how every single computer program works.

It is thus no surprise that the trial court judge found last year that the patent invalid because it was too generalized. The judge specifically noted that the patent “illustrates the danger that exists when the novel portions of an invention are claimed too broadly.” Much like Nelson’s attempt to patent an entire field of coated frozen treats, Rosenfeld’s attempt to patent a large chunk of computerized animation led his patent into dark waters.

As the Supreme Court has explained numerous times, patents are intended to benefit the public by disclosing inventions that might otherwise be kept secret or not even made. The patent system is an exchange of knowledge for monopoly rights. But for both the Eskimo Pie and the animation patents, the heart of the invention, the really difficult part, was still secret. The actual formula for the chocolate coating is found nowhere in the Eskimo Pie patent, and the complete list of lip synchronization parameters is not in Rosenfeld’s patent.

* * *

Though the Eskimo Pie appears to have been the first chocolate-covered ice cream bar on the market, competition arose quickly. This was probably in part due to the popularity of the Eskimo Pie itself, but it was likely also just the result of growing market interest in ice cream. Industrialization in the early 1900s brought new safety standards, packaging machinery, and manufacturing technology to the ice cream industry, rapidly increasing the dessert’s popularity. So it seems likely that at least some of this competition was not mere copying of the Eskimo Pie, but simply coincidental independent invention.

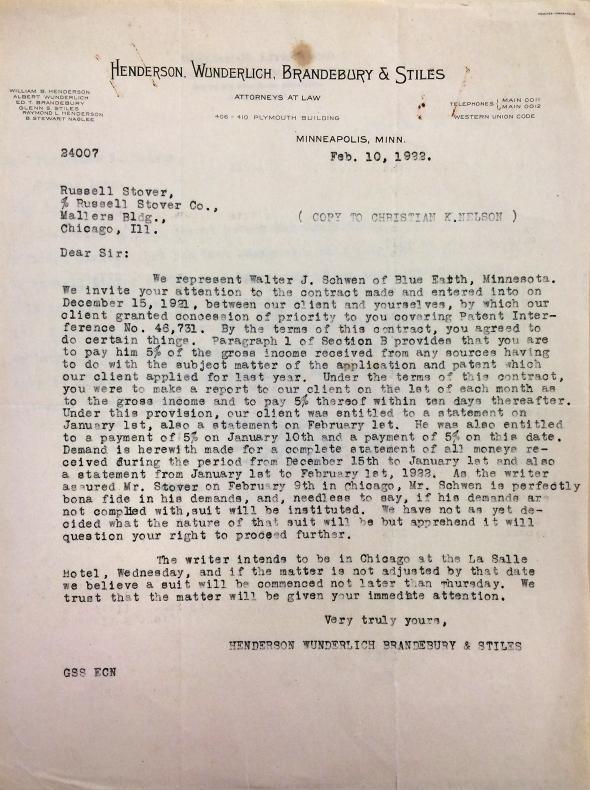

Indeed, there were even competing claims of who invented the first chocolate-covered ice cream bar. Walter J. Schwen of Blue Earth, Minnesota, claimed to have invented the chocolate-dipped ice cream bar, triggering an “interference” dispute at the Patent Office over who was the first inventor. Apparently, the Eskimo Pie Corp. ultimately agreed to pay Schwen a 5 percent royalty to settle the interference.

Image via Public Domain

So the Eskimo Pie faced plenty of competing ice cream novelties, but Americans still bought lots of Eskimo Pies—1 million pies a day by spring of 1922. What made the Eskimo Pie so successful? It’s hard to believe that the patent caused the success, considering that the patent had just been issued in January of that year. Instead, the Eskimo Pie’s success seems to be the result of a desirable product and Russell Stover’s business acumen with franchising.

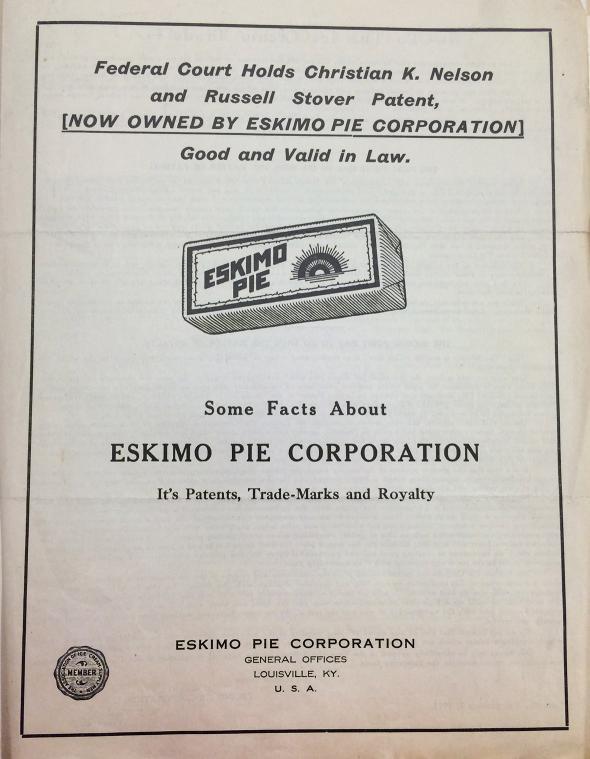

Nevertheless, the Eskimo Pie Corp. wanted to use its patent, so it sued competitors—at least one of which quickly gave in. On June 5, 1923, the company stipulated to a court order against the Sundae-ette Co., with that competitor agreeing to refrain from “trespass upon or infringement of plaintiffs’ said patent.” The Eskimo Pie Corp. trumpeted the court order, printing up a pamphlet titled “Federal Court Holds Christian K. Nelson and Russell Stover Patent … Good and Valid in Law.”

But the celebrations were short-lived, because all this patent litigation cost the Eskimo Pie Corp. $4,000 a day in legal fees (or about $53,000 a day in 2015 money). Russell Stover would sell out his share of the company in 1923, leaving to start his eponymous candy company. A year later Christian Nelson sold the nearly broke company to the manufacturer of Eskimo Pie wrappers, the U.S. Foil Co. (later renamed the Reynolds Metals Co.).

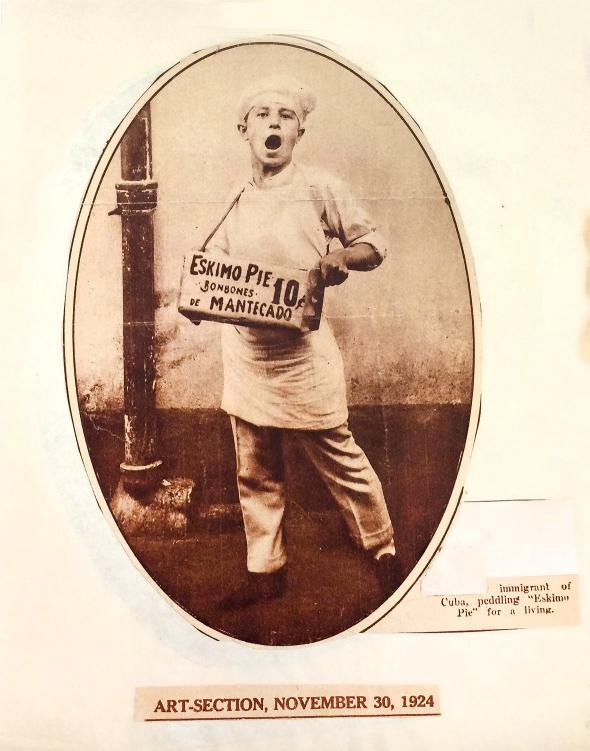

Image via Public Domain

Even following this selloff of the company, U.S. Foil continued with more lawsuits, until the patent was ultimately invalidated in 1928. In two decisions, courts in New York and New Jersey referred to a 1907 book titled Thirty-Six Years an Ice Cream Maker, which described a dessert called “Ice Cream Cannon Balls” that were spheres of ice cream coated in chocolate, and a German patent from 1913 that described “liquid or pulpy contents” that were frozen and then coated “in the usual way” with chocolate or other materials.

Ultimately, it was the breadth of the patent that dragged the company down. The Eskimo Pie Corp. tried to grab more patent rights than it deserved, and it was then forced to defend those excess rights at great cost. The patent and the company’s finances were placed under too much heat and pressure, and like an ice cream bar in an oven, they simply melted away.

* * *

The Eskimo Pie patent and its decade of litigation teach us several important lessons about the patent system.

First, even patents that appear obvious and improperly issued at first glance still require years of court proceedings to invalidate. This has not changed over more than a century. Patent lawsuits today can cost millions of dollars to complete. Many competitors thus choose the Sundae-ette Co.’s route, agreeing to a patent holder’s terms, rather than going through the process of having the patent declared invalid. This makes even the most questionable patents potentially highly valuable assets. And if those patents do end up being challenged, then courts are forced to deal with patents ranging from the simple (sending out mass emails) to the bizarre (fish frozen in an ice cream freezer).

This suggests two fixes. First, lower-cost procedures for reviewing the validity of patents could circumvent the dragged-out litigation process. Second, reforms to streamline and reduce the costs of patent litigation could make the task of contesting invalid patents more palatable. Efforts are underway within Congress to implement both of these, though those efforts have met resistance from the companies that profit most from patents being unassailable at all costs.

But there is a broader lesson of the Eskimo Pie patent story, one about the proper place of patents in the world of innovation. It is sometimes said that patent protection is the best way to encourage new innovation. Some go so far as to say that patent protection is essential to new innovation. But the Eskimo Pie patent challenges those notions. That patent served almost the opposite purpose, entangling the company in years of litigation, draining the success of a well-received product, and ultimately bankrupting the company.

Image courtesy the Denver Post

Today, software companies have numerous other reasons to innovate and develop new products, such as the first mover advantage and the natural monopoly benefits of network effects (think Facebook being successful due to having a large user base). One survey of software entrepreneurs found patents to be the least effective tool for enhancing a company’s “ability to capture competitive advantage.”

Indeed, many leaders in the technology industry have turned away from obtaining patents, finding that they offer “small protection indeed against a determined competitor.” They avoid patents to avoid becoming like the Eskimo Pie Corporation, too tied up in litigation to keep the company afloat.

* * *

If the Eskimo Pie Corporation had obtained a patent of more reasonable breadth, maybe it would have continued to innovate, dreaming up new treats to delight a willing public, rather than resting on the laurels of an overbroad patent. For patents can encourage inventions, but they can also forestall new ideas—follow-on innovations—that build upon those inventions.

Indeed, it is follow-on innovation that gave us the ice cream novelty most familiar to us today. When Christian Nelson first made his original I-Scream Bar, he put it on a stick for holding. Russell Stover convinced Nelson to take the stick out, saying that the stick made the product look too much like a lollipop. The Eskimo Pie ended up being sold stickless. The mass marketing of a chocolate-coated ice cream bar on a stick would require a new visionary who would see beyond the Eskimo Pie, a man named Harry Burt, who would go on to found the Good Humor company.

The author would like to thank the Archives Center of the National Museum of American History for providing access to its collection of documents donated by the Eskimo Pie Corp.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.