This week, the Librarian of Congress will issue rulings on requested exemptions to Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Section 1201 makes it illegal to get around the digital locks that control access to copyrighted content. But sometimes there are good reasons to break digital rights management—like when you want to know how your body is interacting with your medical device—which is where these rulings come into play. They’re designed to reduce the impact of 1201 on legitimate activities that don’t infringe copyright. Unfortunately, the whole process for determining these exemptions is broken, arduous, and unpredictable. In trying to bring copyright law into to digital era, the DMCA’s lawmakers may have unleashed an administrative nightmare.

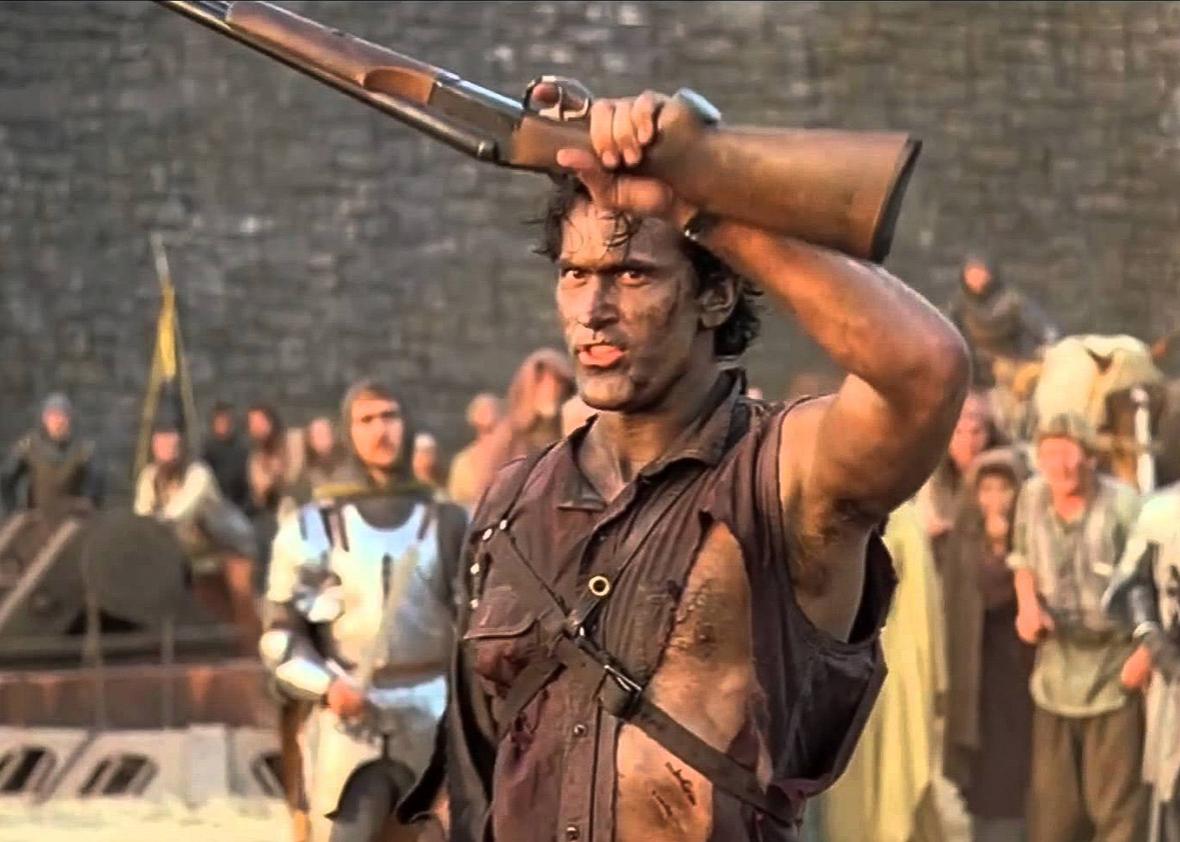

There’s a surprising parallel between this situation and Sam Raimi’s 1992 horror-comedy classic Army of Darkness, in which a portal transports supermarket clerk Ash Williams (along with his car, shotgun, and chainsaw) to 1300, where he’s immediately imprisoned by the medieval land’s inhabitants. Ash’s primary goal is to get back to modern times—and he needs the Necronomicon to do it. Once he finds the book, Ash is supposed to say a magic phrase to dispel the malevolent Deadite forces from the land and return home. Unfortunately Ash fumbles the phrase, unleashing an undead army upon the past.

Similarly, by 1998, modern technology had outpaced the development of copyright law, leaving copyright law with the power to trap technology in a bygone era by interfering with the development and use of important new tools. So, lawmakers tried to create a safeguard for new technologies and emerging user practices—in a law called the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. But, like Ash, in trying to bring copyright law into to modern times, the lawmakers bungled the formula and released an army of obstructive bureaucratic processes on innocent technologies (and more importantly, their innocent users).

Section 1201(a)(1) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act makes it illegal to “circumvent a technological measure that effectively controls access to a copyrighted work.” Anyone who violates this prohibition is subject to severe civil and even criminal penalties. This law was intended to deter people from getting around digital locks and infringing copyrights. But the law doesn’t prohibit only circumventions for the purpose of copyright infringement—it can also be read to prohibit circumventions for any other purpose—even using a Bluetooth-enabled chainsaw to carve your way through a pack of werewolves. In fact, in the 17 years since the law was passed, it’s been subject to abuse by companies that want to restrict consumer choice, discourage safety and security research, and inhibit market competition.

Given that this law can prevent a wide range of activities, Congress created a process to protect legitimate uses of technologies and creative works, and to preserve users’ expressive rights. Under this process, every three years the Librarian of Congress and the Copyright Office are required to conduct a “triennial review,” and the librarian must grant exemptions for particular noninfringing uses that “are, or are likely to be, adversely affected” by Section 1201.

Unfortunately, in practice, this process itself is an administrative nightmare. Even in areas where the law clearly identifies a particular use as noninfringing, exemption seekers bear the burden of persuading the Copyright Office that their request should be granted. And the librarian may grant an exemption and reject another in rulings that are apparently inconsistent. In 2012, for example, the librarian ruled that although smartphones produced before 2013 could be unlocked to work with a consumer’s chosen service provider, tablets could not.

Further, exemption seekers are forced to return, again and again, to the administrative battleground if they want to preserve their exemption (and keep their technologies safe from persecution). There’s no guarantee that an exemption once granted will continue to stand, and therefore no certainty as to the continuing legality of particular practices: At the end of every three-year cycle, petitioners must fight for the rights of consumers and researchers to use their technology legally, in a repetitive, seemingly endless, battle against objections that, no matter how often they are defeated, are resurrected again and again from their earthly slumber. In 2006, the Copyright Office recommended an exemption for visually impaired people to hack their e-books into an accessible format, and then in the next cycle, recommended against the very same exemption request, even though no opposition was raised.

The story of cellphone unlocking demonstrates this point. In both its 2006 and 2010 rulings (sometimes the results from the “triennial” review leak into the following year), the librarian granted exemptions for cellphone unlocking, but in 2012 the old restriction was resurrected (for phones made after Jan. 1, 2013), and cellphone unlockers were thrust under a cloud of illegality. Even when Congress intervenes in response to an exemption ruling, as it did in 2013 when it passed a law temporarily legalizing cellphone unlocking, there’s no guarantee that the Copyright Office and Librarian of Congress will follow its lead. That law expires this year, and once again consumer and industry advocates must take their chances in the rulemaking. The seemingly arbitrary and unpredictable nature of these proceedings means that we will continue to exist in an environment of legal uncertainty—an environment that will discourage consumers, researchers, and developers from investing in useful emerging technologies that rely on circumvention.

But there is one crucial difference between Ash’s situation and ours under the DMCA, and it illustrates why this whole process became necessary in the first place. Ash could adapt his modern technology to suit his changed circumstances. He could fix and modify his 1973 Oldsmobile (a little extra armor here, a spinning blade there) so it was fit to ride into battle with the Deadites. Our technology, on the other hand, including our cars, cellphones, and e-books, potentially contains digital locks, “technological protection measures” that keep us from using our stuff in the ways that work best for us and that prevent us from adapting our tools to new and challenging circumstances (i.e., fighting off the undead horde).

The terrifying tales of these potential technological protection measures gone bad are legion—you don’t have to dig deep to unearth stories of cars hiding (malicious) code and dangerous defects behind digital locks, cellphones that can’t be moved from one service provider to another, medical devices that won’t tell you what your body is doing, and 3-D printers that refuse to work with alternative materials. We’ve also seen these locks work against important social values, like privacy and accessibility, in televisions that can’t be made not to spy on you, CDs that infect your computer with vulnerabilities, and e-books that can’t be adapted for visually impaired readers. In each of these circumstances, the technology that provides the lock can be circumvented—but not without invoking the wrath of the DMCA.

This means that those who want to legally adapt, alter, or investigate these technologies (and others) will have to keep returning to battle the army of undead objections to their exemptions, in sequel after sequel, until Congress decides to end this insanity and revise the DMCA.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.