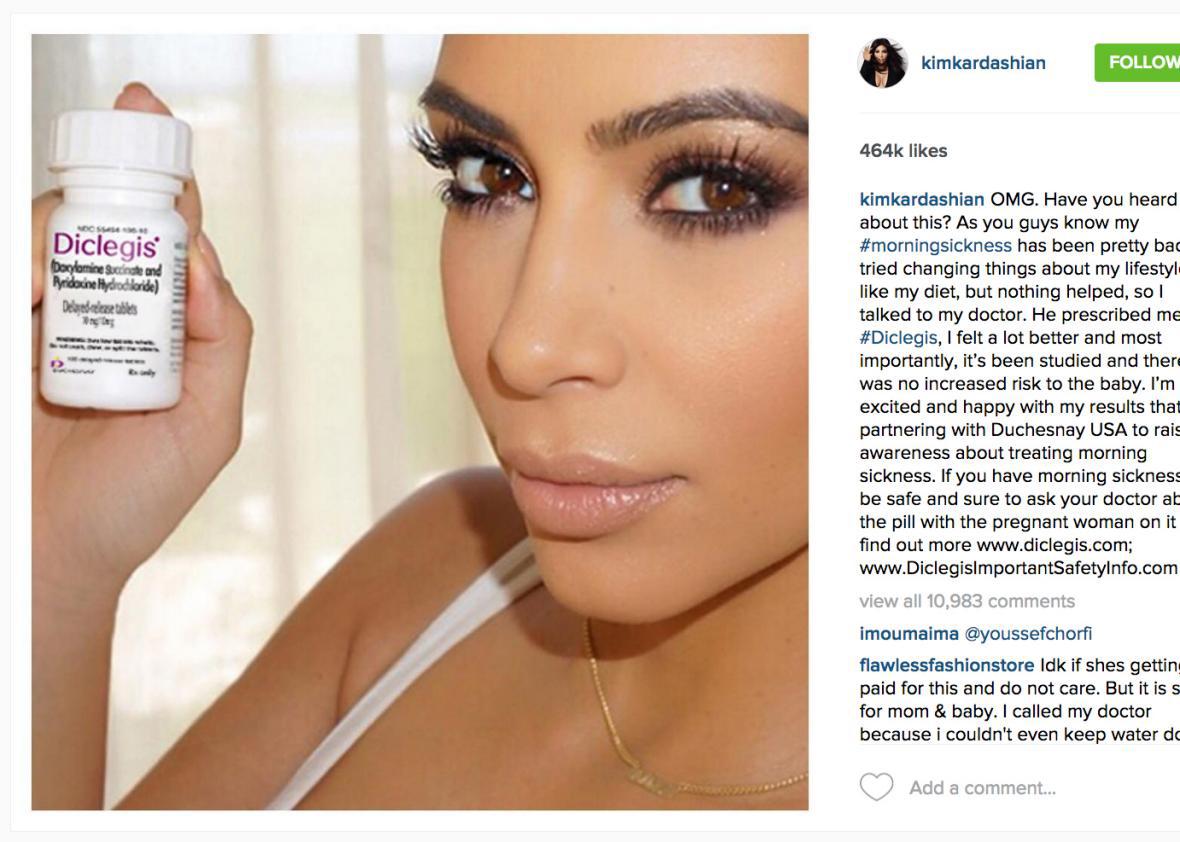

Kim Kardashian has a long history of social media notoriety. But her most serious transgression yet didn’t violate Instagram’s terms of service—it violated federal law. After Kardashian promoted prescription morning sickness pills on her Instagram account, the Food and Drug Administration sent her a stern warning demanding she take the post down immediately. Kardashian is paid by Duchesnay USA to promote the drug, called Diclegis—but her Instagram post touted its benefits without mentioning its associated risks. As it turns out, advertising prescription drugs without noting their side effects is against the law, even when a reality star does it. Kardashian promptly removed the offending post.

Neither Kardashian’s pill hawking nor Duchesnay’s profit mongering is particularly admirable. But the KK–FDA kerfuffle raises serious questions about both free speech and public health. It seems quite unlikely that the FDA’s stringent regulation of social media drug promotion can withstand constitutional scrutiny. Social media platforms—not the government—should take the reins and curb Kardashian-style promotion directly.

Instagram/People magazine

From the dawn of the Supreme Court’s commercial speech jurisprudence, pharmaceutical advertising has found significant protection under the First Amendment. In 1976 the court struck down a Virginia measure barring pharmacists from advertising the prices of prescription drugs. Both individuals and society as a whole, the court explained, have “a strong interest in the free flow of commercial information.” In 2002 the court built on this logic, striking down a federal law prohibiting pharmacists from advertising “compounded drugs,” or a combination of different medicines. The government argued that the marketing ban was necessary because advertisements didn’t “fully explain the complicated risks at issue.” But the court shrugged off this concern, stating that, so long as the advertisements are not misleading, they could not be outlawed.

Then, in a 2011 case called Sorrell v. IMS Health, the court elevated pharmaceutical advertising to an even higher plane of constitutional protection. Invalidating a Vermont law forbidding doctors from selling prescription data to drug companies, the court announced that the state had unconstitutionally restricted “protected expression.” The court applied heightened scrutiny to the law, finding that it violated pharmaceutical companies’ free speech rights to access and distribute data. “Speech in aid of pharmaceutical marketing,” the court declared, “is a form of expression protected by the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”

Since Sorrell, lower courts have taken the justices’ hint and broadened the free speech rights of drug companies, pharmacists, and “detailers”—pharmaceutical representatives who encourage doctors to prescribe certain drugs. Just last Friday a federal district court ruled that the government cannot bar detailers from encouraging doctors to prescribe drugs for non–FDA-approved purposes. Drugs are sometimes approved by the FDA to treat one malady but later proved to effectively treat another. The FDA sought to block detailers from promoting this secondary, “off-label” use to doctors. But the court found that doing so would qualify as unconstitutional censorship. So long as the detailers’ speech is “truthful and non-misleading,” the court held, the FDA has no power to forbid it.

Kardashian’s promotion would probably find constitutional protection under this framework. She didn’t lie or hawk an illegal product: She encouraged the proper use of a legal drug, providing accurate—if incomplete—information to her followers. As a paid promoter of Diclegis, Kardashian certainly has a financial interest in pushing the drug. But her Instagram post was still fundamentally expressive, much like detailers’ pitches to doctors. Duchesnay may be constitutionally required to note side effects in every commercial it creates for Diclegis. But when it pays a celebrity—or a detailer—to promote the drug, she holds her own free speech right to say what she wants about it. For better or for worse, that’s the Supreme Court’s current theory of the First Amendment.

If the Constitution proscribes the government from intruding into the marketplace of ideas, however, it says nothing about Instagram’s ability to shut down speech. Kardashian has 42 million Instagram followers—a group of self-selected fans and train-wreck oglers who have voluntarily chosen to join a private platform and subject themselves to her daily slew of selfies. When Kardashian slips an ad into this stream of posts, Instagram doesn’t have to tolerate it. The company should join other social media platforms in shutting out pharmaceutical companies from its walled garden. Some, like LinkedIn and Facebook, already bar pharmaceutical advertising; others, like YouTube and Pinterest, place significant restrictions on them. These platforms are moving in the right direction.

It’s easy to see why pharmaceutical companies want access to this kind of space. The marketing opportunities on social media are endless; Kardashian’s post, for instance, got more than 460,000 likes and who knows how many doctor referrals. Those companies argue that the FDA is being unreasonably overbearing in its restrictions on social media. That’s basically true. But while the government can’t limit big pharma’s free speech, social media platforms not only can but absolutely should. These are private companies we’re talking about; they have no obligation to let drug companies advertise in their space. (In fact, they likely have a First Amendment right to exclude information or advertising they dislike.)

Ads like these only make social media sites less trustworthy, spammier places to be. Instagram says it wants to create a “positive and healthy community” and foster “an authentic and safe place for inspiration and expression.” In this spirit, the photo-sharing platform has already taken steps to purge itself of offensive content like spam, graphic images, photos glorifying self-injury, and certain types of nudity. If that’s the goal, then Instagram should take the next step, and ban users from using the space to hawk drugs. Those kinds of ads exist solely for the benefit of pharmaceutical companies, and to the detriment of fans who just want to scroll through Kim’s selfies in peace.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.