Does Facebook filter our political discourse? Last week, the company released a study of user profiles that purported to show that the social network’s News Feed algorithm doesn’t limit our access to diverse and opposing political points of view. Rather, it said, the narrowness of our Facebook conversations is a result of how we naturally behave. Facebook didn’t create the so-called filter bubble, the authors claimed; it merely reflects it.

I looked closely at some of the raw data Facebook shared in the study’s (partial) replication materials. The data doesn’t tell you so much about how Facebook filters News Feeds, but it does tell you a lot about how people share news. Those shares can tell you a lot about who reads what on Facebook and, more significantly, who doesn’t read what. Not all Facebook users are in filter bubbles, but some of them definitely are. Where many of us are willing to encounter some other political viewpoints—or at least attain bipartisan agreement over orangutans and Tina Fey—it turns out Facebook users on the far left and far right primarily read and share stories tailored exclusively to their opinions. Their echo chambers are welded shut.

The study, published in Science under the title “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook,” has its faults and has taken some heat for limiting its population set to U.S. users who explicitly declared their political alignments on their profiles and chose political alignments that could be classified on a one-dimensional spectrum: from very liberal, to liberal/Democrat, to moderate/centrist, to conservative/Republican, to very conservative. Many political views do not fit on this scale. As Facebook representative William Nevius told me, libertarians, anarchists, and other groups were excluded from the study. (I assume my declared membership in the Nonière Beezwax party ruled me out, too.) In fact, only about half of the 20 million Facebook users with explicit political views chose categories that Facebook could fit on the scale, narrowing the study population to 10 million users. So Facebook only analyzed those users who classified themselves within the conventional wisdom of what constitutes American politics.

Although the study certainly doesn’t justify the researchers’ statement that “we conclusively establish that … individual choices more than algorithms limit exposure to attitude-challenging content,” it does, as Zeynep Tufekci points out, reveal the narrow exposure of certain groups to certain types of content inimical to their political viewpoints. The study just makes it difficult to gauge the magnitude of those effects. As I’ve written, big data is messy and imperfect, and we need to be very cautious when drawing conclusions from it.

But if we remember that we’re looking at a population that tacitly accepts the conventional continuum of American politics, the data itself is a gold mine. By classifying 700,000 URLs of so-called hard political content, Facebook has given us a fascinating look at what kinds of audiences visit and stay away from that content. Facebook gauged whether these sites were shared mostly by liberals, mostly by conservatives, or roughly equally by both, dividing the scale into quintiles and terming the middle quintile “bipartisan.” Using this data, it then calculated each website’s overall “alignment” rating to judge which audiences tended to share its contents. Facebook used this data to gauge how much “cross-cutting” content there was between liberals and conservatives. The study found that Facebook does indeed mildly suppress such content from people likely to disagree with those stories—but that self-identifying liberals and conservatives are unlikely to click on stories that don’t align with their worldviews anyway.

Yet the raw quintile scores are fascinating in themselves, because they reveal, among other things, how closed our silos really are. Take Facebook shares of tweets. While Twitter averaged out as a roughly bipartisan website, it had a unique—and uniquely horrible—saddle-shape distribution. Twitter content is shared considerably more often with like-minded audiences than broad audiences. In other words, most shares of tweets by liberals on Facebook went to liberals, and most shares by conservatives went to conservatives; there was far less cross-cutting content than with most bipartisan sites. This hints that Twitter is a place for extremists, partisans, and ideologues to preach to the converted, not where people go to find atypical or unorthodox political content to share or debate. Unfortunately, since both dug-in political sides are on Twitter, the sides can’t help but run into each other. The study suggests that Twitter is two echo chambers that hate each other, with each struggling to be louder. (Though the left is winning by far, at least on Twitter.)

Twitter, however, is an extreme anomaly. Most bipartisan sites did indeed feature content that was shared by the middle of the political spectrum as well as the ends, though with a couple exceptions (Wall Street Journal, Reason, and Zero Hedge), they tended to have more liberal appeal than conservative appeal. The websites of local television stations stood out as providing the most bipartisan content by far, with far fewer stories appealing only to one side. Most other bipartisan sites provided a mix of liberal-appealing, conservative-appealing, and bipartisan content.

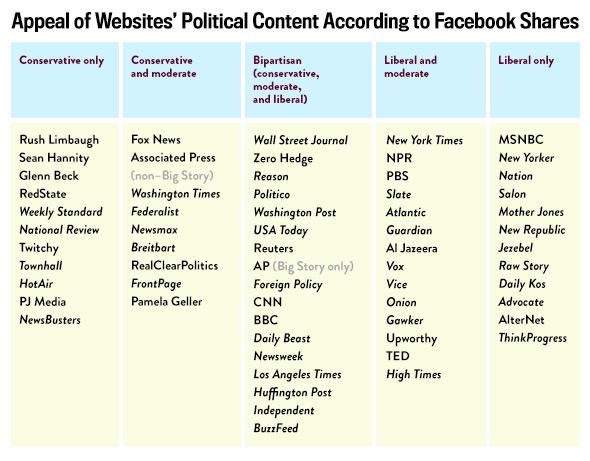

Using Facebook’s data, I’ve classified a handful of websites into five buckets depending on the approximate breadth of their appeal:

Chart by Slate

There are two gullies on the extremes: sites not only bereft of content that appeals to the opposite side, but even of content appealing to moderates. These sites are interesting because of their narrow partisan appeal—not because their content is necessarily partisan, which Facebook didn’t set out to measure, but because of their narrow readership, which suggests that even if these sites produced content that might appeal to the other side, the other side would fail to read it or share it. Moreover, moderates are sufficiently turned off by these partisan sites that they never bother with them.

On the right, these sites are pretty much what one would expect: Rush Limbaugh’s website, Sean Hannity’s website, RedState. So too on the left: Salon, Daily Kos, Jezebel, MSNBC. (Unlike Fox and even Al Jazeera, MSNBC seems to have almost no appeal to moderates.) Based on Facebook’s data, I suggest these sites are locked into a feedback loop of increasingly feeding red meat (or blue meat) to a hungry partisan base, which aggressively shares their content among like-minded friends, while moderates and opponents ignore them. This goes for Salon just as much as Rush Limbaugh. While the omission of users with undeclared political views limits the reach of the study, these “partisan” classifications are sufficiently strong and narrow as to be a good predictor of a limited appeal to Facebook users with undeclared political views. (It would be interesting for Facebook to reveal what proportion of per-site shares come from politically declared and politically undeclared users, and whether a higher proportion of politically declared users share content from partisan sites.)

Before someone on one of these partisan sites accuses me of false equivalence, remember that the equivalency here is one of structure, not of content. Like it or not, the evidence suggests that these partisan sites pursue similar courses of appealing to readers. Maybe one side is 100 percent right, and the other is 100 percent wrong (on climate change, for example). But their readership models and the narrowness of their appeal is the same; to the extent that some of their content is not partisan, it is still primarily read by partisans. And although Facebook may be premature in saying that it is not contributing to the filtering of alternative viewpoints, I believe it is warranted to claim that the sharers of these ultrapartisan sites are beyond being convinced by opposing views.

It comes as some relief to me, frankly, to see that Slate still has a significant appeal to moderates, if not to conservatives. Slate comes in low in terms of truly bipartisan content shared significantly among both liberals and conservatives, but much of its content does appeal to moderates, which means that its opinions do penetrate that much further beyond the strictly defined limits of “liberal.” My point is not that sites should reach toward moderates, but that they should reach beyond narrow partisan bases: Breadth is more important than bipartisanship. I interpret a lack of moderate readers to point to a lack of broader appeal in general and to dogmatic acceptance of these partisan sources. I don’t know of too many libertarians, anarchists, or autonomists reading Jezebel, for example.

There is a lesson in all this for readers, as well: Don’t limit your reading to these partisan sites. That doesn’t mean Salon diehards have to read Rush Limbaugh, nor does it mean that sites outside of the two gullies are necessarily better in quality. (Fox News’ moderate appeal doesn’t redeem it in my eyes, and I stand by my work for the Nation.) Rather, getting some sense of wider perspective is beneficial because you’ll be reading stories that aren’t targeted at people who think exactly like you do. Facebook may shape your opinions in part through curating your News Feed, but those partisan websites do a far better job of it.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.