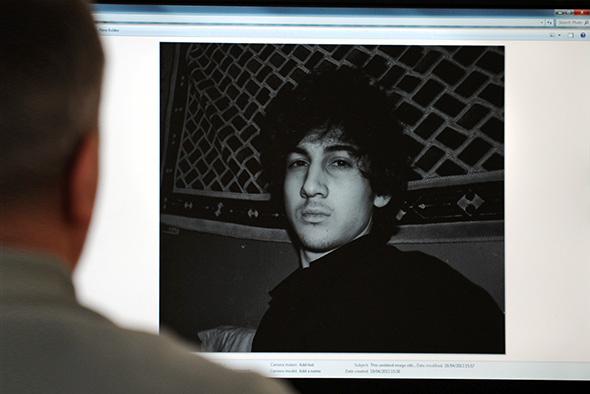

As we approach the second anniversary of the Boston Marathon bombing, many of us here in Massachusetts and beyond are riveted by the ongoing trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev. We all pretty much know what happened, we all know who did it, and still, for some reason, even the tiniest details hold a certain fascination. So last week, when the 28-page questionnaire completed by more than 1,000 prospective jurors was released, I found myself reading through it, trying to get a glimpse into the nearly two-month-long jury selection process that stretched over a string of brutal Boston snowstorms.

Some of the questions posed to the jury have obvious ties to the case, in which the defense is claiming that Dzhokhar’s older brother, Tamerlan, was the ringleader of the plot. So you can see why the lawyers would be interested in jurors’ response to the question, “Do you believe most teenagers are easily influenced by older siblings?” Others try to probe racial and religious biases relevant to the defendants (“Do you have strongly held thoughts or opinions about Muslims or about Islam?” “Do you have any beliefs, attitudes, or opinions regarding Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Chechnya, or Dagestan, or the people who live there … ?”)

But I had more trouble puzzling out question 24: “If you have studied ballistics, explosives, arson, criminology, terrorism, computer science, crime scene investigation, or law enforcement, please describe your training.” How did computer science land on that list? When did it become something we speak of in the same breath as explosives, arson, and terrorism? What could a juror possibly need to know—or, perhaps more accurately, need not to know—about computer science to understand this relatively low-tech case about guns and pressure cooker explosives?

The Boston Marathon bombing is not a cybersecurity story, but, inevitably, we come back to computers in the courtroom. On Monday, FBI agent Kevin Swindon testified about searching Tsarnaev’s laptop, desktop computer, external hard drive, two thumb drives, cellphones, and iPods. The files on those devices included articles titled “Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom” and “Jihad and the Effects of Intention Upon It,” as well as the more mundane trappings of college student life: class essays, a résumé.

You hardly need a background in computer science to follow the narratives put forward by each side about the digital evidence. To the prosecutors, it’s a sign that Dzhokhar pursued militant interests independent of his brother and over an extended period of time. Meanwhile, defense lawyer Judy Clarke said in her opening statement that Dzhokhar “spent most of his time on the Internet doing things that teenagers do: Facebook, cars, girls.”

There are other arguments—for instance, that Dzhokhar’s devices may have been accessed and used by other people, including his brother, or Clarke’s claim that there is no evidence of Tsarnaev “searching the Internet to find” the militant materials on his devices—but those are far from deeply technical claims. So why would the lawyers want to screen jurors for knowledge of computer science?

One possible explanation is that too much technical knowledge might make jurors less likely to take testimony about digital evidence at face value. Jeffrey Abramson, professor of government and law at the University of Texas at Austin, told me, “You never want a juror to be the witness. You never want a juror to go into the jury room and say, ‘Well, I know that they said this about the forensics but I work in this area, I’m an expert on this, and it isn’t that way it’s this way.’ You lose control of the case and you lose control of the jury.” Juror questions can help lawyers assess intangible attitudes and biases like these in a variety of different ways, not just by asking about educational and employment history, Abramson added. He cited questions on the Tsarnaev juror survey about what news sources respondents read regularly as one means of inferring general political views and opinions.

Some technology-related questions, like the ones on the Tsarnaev questionnaire about social media use, blogging, and online comments, can help lawyers infer those opinions more individually. “What you’re seeing here is not so much a concern with jurors’ ability to process technical information,” said Jeffrey Frederick, author of Mastering Voir Dire and Jury Selection: Gaining an Edge in Questioning and Selecting a Jury, and director of the Jury Research Services Division at National Legal Research Group Inc. “[Lawyers] are more interested in the jurors’ footprint on the internet. They’re going to be looking at the Facebook pages and blogs to see if those things can help them better understand this juror.”

In the days before social media, lawyers sometimes resorted to more unconventional means to try to screen for case-specific biases. For instance, potential jurors for the O.J. Simpson trial were asked on their questionnaire whether they or any members of their immediate families had had an amniocentesis procedure, because the defense wanted to screen for people who had had a positive experience with genetic testing that might influence their opinion of the DNA evidence, Abramson said.

But while the amniocentesis question was an “outlier,” Abramson noted that it’s fairly standard practice to ask potential jurors about their occupations and to make some assumptions about certain professions. “When I was first starting in the prosecutors office, I was told, ‘Beware of having social workers on the jury because they always think there’s an explanation other than culpability,’ ” he said.

I tried to imagine the equivalent warning applied to my field: “Beware of having computer scientists on the jury—they always think there’s another explanation for the digital evidence.”

In some cases, a little technical know-how might actually be viewed as useful for jurors. The questionnaire administered potential jurors used in the 2013 trial of Gilberto Valle, the so-called cannibal cop whose case made heavy use of his online chats from DarkFetishNet.com, included an entire section of questions about “experience with computers and exposure to pornographic materials.” These questions ranged from asking people how much time they spent online and whether they used email, instant messaging, search engines, Facebook, or file sharing programs, to whether they knew what Second Life was, or had ever visited sexually explicit websites. When the jury in that case was finally selected, four of the jurors had backgrounds in computer science, and all said they used the Internet daily for at least an hour.

The Tsarnaev trial questionnaire did not delve into respondents’ online activity in anywhere near as much detail—though it did screen for social workers, among others, in question 23: “If you have studied law, medicine, psychiatry, psychology, counseling, sociology, social work, or religion, please describe your training.”

Frederick said that the question about lawyers and doctors was more standard of juror questionnaires, while the one about ballistics, terrorism, and computer science seemed to be tailored more specifically to the particulars of the Tsarnaev case. But screening for computer expertise is “becoming a more regular occurrence” during jury selections, he added. “We’re seeing a lot of technical evidence come in, and the way that evidence is presented at trial is taking a more technological focus.”

That all makes sense. Still, juxtaposed with the previous question, lumping computer experts in with specialists on ballistics and terrorism seemed odd, even unfair. Why couldn’t computer science be included in the other list? Why couldn’t we keep the company of lawyers and doctors and social workers, rather than the people devoted to the study of crime and violence?

Abramson suggested that the distinction likely reflected the difference between trying to screen for people who have “backgrounds that make them natural leaders” (those would be the lawyers and doctors and psychiatrists) versus pinpointing people in fields related to technical evidence specific to the trial.

Since digital evidence plays a role in many investigations these days, perhaps that means computer scientists are off the hook for good when it comes to jury duty. But does that really make sense in a world where even technically unsophisticated criminals (perhaps especially technically unsophisticated criminals) are going to leave digital footprints? There’s something about screening jurors’ computer science backgrounds that seems a little like a relic, leftover from a time when digital evidence was less common and the technology understood by only a select few. Now that an introductory computer science class is the most popular course at Harvard, perhaps it’s time to stop regarding this as an obscure, specialized body of knowledge on par with expertise in arson or crime scene investigation.

Read more of Slate’s coverage of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s trial.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.