In the past few months we’ve heard a lot about two opposite Internets, one infernal and one heavenly.

The infernal Internet emerges from the recent debate over net neutrality. Naturally, this Internet lives underground, a pandemonium of overlapping and redundant wires accumulated over the past half-century. In the undersea cables and repurposed telegraph vaults of this Internet, greed rules. A cutthroat competition for nanoseconds of advantage has companies grappling ceaselessly for real estate. The titans of this Internet rent space in orgiastic facilities where they jack into one another via unholy “peering arrangements,” bypassing the common Internet and edging out possible newcomers. Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler had to descend into this inferno this February like the Archangel Michael, routing the cable industry’s monopolistic control over “last-mile” consumer broadband in this country.

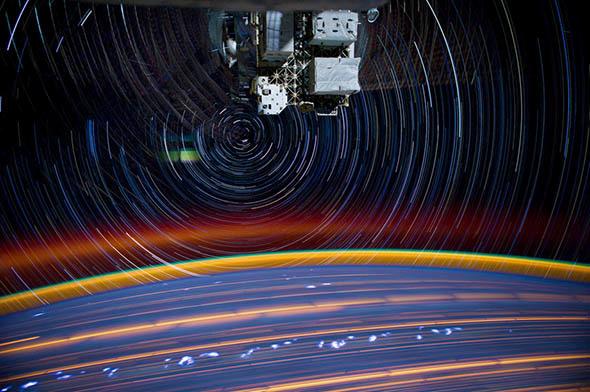

Meanwhile, a heavenly Internet is taking shape above our heads. In the same week this January, the spaceflight companies SpaceX and Virgin Galactic both announced plans for “megaconstellations” of low-Earth orbit, or LEO, satellites delivering broadband to every inch of the inhabited world. (Disclosure: I spent some time last year working for SpaceX on unrelated projects.) Instead of greed, this Internet is said to be propelled by philanthropic purpose. The satellite schemes join the host of projects aiming to bring connectivity to areas cable can’t reach. Instead of devils, this Internet has saints: Richard Branson promising to “transform the world,” Elon Musk battling the defense-aerospace-industrial complex, Eric Schmidt of Google taking a chance on routers strapped to helium balloons, and Mark Zuckerberg executing surgical strikes on global poverty with Wi-Fi–equipped drones. There’s profit to be made among the roughly two-thirds of humanity that remain unwired, of course, but its pursuit seems beatified by the messianic pursuit of one digital family of man.

The details aren’t quite as sanctified. Ungodly quantities of lucre are flowing into these projects, along channels that seem to follow the contours of corporate competition rather than humanistic interest. SpaceX’s plans secured the company $1 billion of backing from Google and Fidelity, and Virgin bought its entry into the Internet space race through a partnered investment with the chipmaker Qualcomm in a venture called OneWeb—founded by Greg Wyler, an entrepreneur who defected from Google and took valuable spectrum rights with him. And behind these high-profile players are several more secretive ventures without any claims to philanthropy. As Space News reports, a glut of filings to the international agency that allocates orbital space hints at an international “gold rush” on broadband satellite.

The reasons for this rush may have as much to do with the already-connected world as with the world-to-be-connected. “Space has been a neglected part of the telecom infrastructure for decades,” says Christopher Baugh, president of Northern Sky Research, which tracks the satellite industry. Until now, most telecommunications satellites have been placed 22,000 miles out in geostationary orbit, where they have to accept the signal lags inherent in such distances. Today’s proposed LEO constellations will spin only 680 miles up, making satellite signal speeds finally comparable, in theory, to cable. If such a constellation were to get off the ground, Baugh notes, it could valuably complement the terrestrial Internet, transmitting long-distance signals faster and reducing congestion in the wired system. “The technology for this is there. There’s just a chicken-and-egg problem with the satellite market, since costs are so high.” By eating those costs through publicity-friendly pushes for connectivity in the developing world, Silicon Valley firms could position themselves for eventual plays at renovating Internet infrastructure in the developed one.

Recently, for instance, OneWeb announced plans to provide airline passengers with high-speed Internet. “We have a focused mission to enable affordable Internet access for everyone,” said Wyler, OneWeb’s founder and CEO, in a phone interview. So what does that have to do with in-flight Internet? “In order to do that we need to build a system at scale. Part of that will come from extending connectivity into rural areas, and part of it will come from applications in aviation, maritime, oil, and gas.” Elon Musk has been more aggressive in his public ambition, claiming that beyond delivering rural Internet, SpaceX’s project is to create “a global communications system that would be larger than anything that has been talked about to date.”

History has not been kind to such ambitions. Satellite Internet, like so much today, is a ’90s throwback. In June 1990, Motorola announced Iridium, a network of LEO telephony satellites. Martin Collins, a historian at the Smithsonian Institution working on a book about Iridium, describes how 20 years before Musk, Motorola sought to capitalize on the “post–World War II idea of the entire planet as a field of human action.” Unveiled only seven months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Iridium was touted as a technological herald of globalization, the largest privately funded technology project of all time. Less than a year after the system went online, Iridium was bankrupt, unable to compete with wired systems. A host of related ventures met similar fates throughout the decade, as the promise of species-unifying connectivity petered out into niche military, transportation, and oil industry contracts. By the new millennium, Iridium phones were most often seen in footage from Iraq.

Technological and legal developments, though, may be giving satellites a second chance against cable. Moore’s law and declining launch prices have made them more affordable than ever. And back in 2010, an industry white paper predicted today’s legal situation: “A pro-net neutrality FCC, a marked change from the FCC under the Bush Administration, generally should tend to level the playing field for satellite broadband service by preventing larger terrestrial providers from entering into preferential deals with content providers.”

Do the companies lining up behind satellite Internet see themselves, over the very long term, competing with Comcast and Verizon as consumer Internet service providers even in developed markets? So far, OneWeb’s public plans focus on partnering with ISPs, delivering back-end support for existing front-end networks. But in a filing with the FCC, SpaceX has described its ambition to “provide high-quality Internet access and other broadband services (including to end users in the United States).” A representative for the company declined to elaborate: “For now, we will let our comments before the FCC speak for themselves.”

Most experts I spoke with don’t see this as a technological possibility within our lifetimes. But Dick David, CEO and co-founder of the NewSpace Global research firm, is more optimistic: “When you consider that light travels faster through a vacuum and that satellites can direct signals through fewer routers, we’re looking at satellites not only competing with cable but also taking a lot of that market share.” Technology on the horizon promises to improve the odds of this: Cisco’s work on “Internet Routing in Space” hints at a future in which satellites are not mere relays for terrestrial signals but actually act as distributed server farms in space. And even if satellite broadband speeds never catch up to cable, it’s not inconceivable that the conveniences of a single global network accessible anywhere might outweigh the lost megabits per second. That’s the definition of disruptive technology.

The proposed constellations would have other advantages of consequence for the digital future. Cable connections are vulnerable to vandalism or sabotage, both of which have become serious problems in Africa. They’re also vulnerable to state censorship, as China demonstrates. A space-borne Internet could skirt these threats. It might also skirt law enforcement and surveillance: While tech companies today often dodge warrants by storing data in foreign countries, the lawless sky offers an even surer refuge. And though net neutrality is the law for now in Europe and the United States, it doesn’t really exist elsewhere. Any network offering satellite Internet to the developing world is likely to sacrifice neutrality for efficiency. The FCC’s regulations are intended to encourage innovation through an “end-to-end” network paradigm where websites and their audiences, rather than the service providers between them, shape how the Internet looks and feels. “We’re confident we will be able to maintain neutrality,” Wyler tells me. “Our system is designed to be very efficient.” But several of the companies currently connecting the developing world are already following a more static, centralized model: Outernet is experimenting with radiolike one-way data, and Internet.org funnels traffic onto Facebook and a coterie of related services.

No matter where it’s based, the Internet is all too mundane, a scramble for profit in the job of trucking the species’ data. The FCC’s February ruling was a welcome blow against a specific clot of power in this system. But disturbed in one place, power on the Internet will seek to reconstitute itself somewhere else. A number of ambitious firms are betting that the path to that power is up.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.