When news of a mass shooting breaks, do you try to find the alleged perpetrator on Twitter? Perusing the social media accounts and online activity of murderers and terrorists has become one of the strangest and most immediate rituals of post-tragedy news analysis. In the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings, we read Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s tweets; following the 2012 movie theater shooting in Aurora, Colorado, we analyzed shooter James Holmes’ online dating profiles; after Adam Lanza killed 26 people at Sandy Hook Elementary School, we learned about his online alter ego, “Kaynbred,” and penchant for violent video games and editing Wikipedia articles about mass murderers. We latch on to these details because they are some of the most immediately available information in the aftermath of inexplicable tragedies about the people who perpetrated them and why they would do such things.

Tracing these online histories tends to highlight both how normal these killers’ Internet activity was—Tsarnaev posted photos of his cat and car, Holmes was looking for love on Match.com, Lanza played popular free shooting game Combat Arms and read Wikipedia—and also the little clues that, at least in retrospect, suggest something more sinister, such as Tsarnaev’s cryptic August 2012 tweet about how the marathon “isn’t a good place to smoke”; Holmes’ sinister appeal to would-be dates: “Will you visit me in prison?”; and Lanza’s creepily specific knowledge of the weapons used by mass shooters.

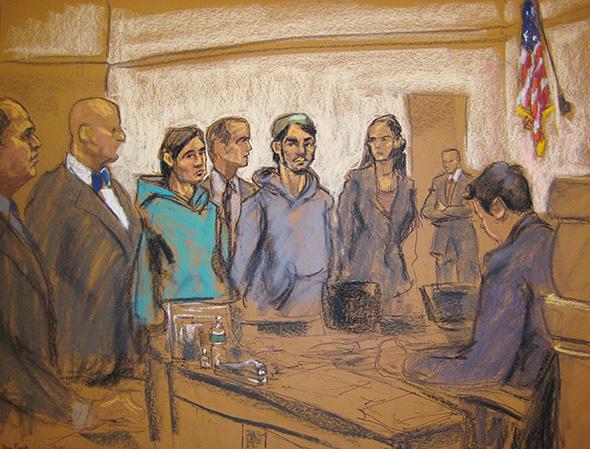

Rarely, however, are these warning signs clear enough to have warranted any pre-emptive intervention. That’s what makes the story of last week’s arrests in New York of two men, who were charged with plotting to aid ISIS after an investigation spurred by their online comments, all the more remarkable and unusual. The trail that led the FBI to Abdurasul Hasanovich Juraboev and Akhror Saidakhmetov—as well as a third man, Abror Habibov, who was charged with helping them—began with an Uzbek-language ISIS recruitment website, Hilofatnews.com, but extended far beyond the Internet.

In a complaint and affidavit supporting the arrest warrant, FBI agent Ryan Singer quotes the Aug. 8 posting on the site (translated from Uzbek) that sparked the investigation:

Greetings! We too wanted to pledge our allegiance and commit ourselves while not present there. I am in USA now but we don’t have any arms. But is it possible to commit ourselves as dedicated martyrs anyway while here? What I’m saying is, to shoot Obama and then get shot ourselves, will it do? That will strike fear in the hearts of infidels.

Even a post as explicitly threatening as this one still leaves room for a fair bit of uncertainty about the author—after all, the Internet is rife with crazy online commenters talking about how much they want to kill people. And the investigators clearly understood this was nothing more than a small, inconclusive clue, since they didn’t move to make the arrests until they had collected piles of other in-person evidence, including numerous recorded conversations, interviews, and Juraboev’s purchase of an airplane ticket to Turkey.

The investigation is in many ways a striking mix of old and new tactics. The online breadcrumbs are undeniably important: The IP address associated with the Hilofatnews post led the FBI to Juraboev’s door in Brooklyn. Why Juraboev didn’t bother to mask his IP address, and how the FBI obtained it, are mysteries left unresolved by the affidavit, beyond a vague reference to “voluntary disclosure of records associated with ‘Hilofatnews.com.’ ” It seems unlikely that the site itself would turn over that information voluntarily, but the information could also have come from a hosting or service provider—and it’s possible the turnover was tied to the site’s apparent removal in August, about a week after the targeted posting.

The IP address is not the only digital clue cited in the affidavit—there are also extensive intercepted online communications (again, the precise mode of interception is left unspecified); an inspection of Juraboev’s iPhone (surrendered voluntarily) to determine that he frequently visited Hilofatnews; and references to other postings on the site, including one by Saidakhmetov, in which he commented on a video of mass executions of Iraqi forces, “Allohu Akbar I was very happy after reading this, my eyes joyful so much victory.”

But, to my mind at least, the most damning pieces of evidence the investigators collected by and large didn’t come from the Internet. These included the in-person interviews in which Juraboev not only admitted to writing the online postings but also reaffirmed his belief in ISIS’s agenda and willingness to assassinate President Obama if so ordered. The confidential informant who approached Juraboev at a mosque in September and recorded conversations with him about his plans to travel to Syria via Turkey provided another crucial link, as did the recorded phone conversations between Saidakhmetov and Juraboev about their efforts to delete Saidakhmetov’s online profile on Russian social network Odnoklassniki to avoid detection by the FBI.

In other words, a lot of old-school sleuthing and legwork went into chasing these men down. That is, in large part, what made it possible for authorities to stop Juraboev before he got on the plane to Turkey and (allegedly) pre-empt the addition of new recruits to ISIS’s army. But it’s not hard to imagine the alternative scenario, in which they successfully made their way to Syria and committed horrible atrocities, and we found ourselves perusing their Internet profiles after the fact, wondering why no one had stopped them back when they first made their allegiances known in online comments.

But the description of the investigation makes clear just how impossible it would be to try to vet every person who threatened the president in an online comment—much less those who write cryptic tweets and creepy dating profiles or edit sinister Wikipedia pages. The tactics the FBI employed to arrest Juraboev and Saidakhmetov don’t scale; they require lots of manpower and time and attention to distinguish the online nutcases from the honest-to-God villains.

The case against Juraboev and Saidakhmetov reads like a no-brainer in the affidavit—over and over they reaffirm their intentions, in online postings, conversations with each other, recordings made by other people—but it also reads like a stroke of luck, and a triumph of good policing, that someone followed that lone IP address so determinedly and diligently instead of just dismissing it as one of thousands, if not millions, of crazy online commenters.

Like Tsarnaev and Holmes and Lanza, Juraboev’s and Saidakhmetov’s public Internet personas were at once unsettling and inconclusive. In the former cases, we look back at their dating profiles and tweets and read malice into them because we know what those men went on to do. For Juraboev and Saidakhmetov that malice comes across not because of what they actually did but because of the painstaking and intensive offline FBI investigation that gave context and meaning to what might otherwise have appeared to be insignificant online idiocy.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.