This essay is excerpted from Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable, and What We Can Do About It, by Marc Goodman, published by Doubleday.

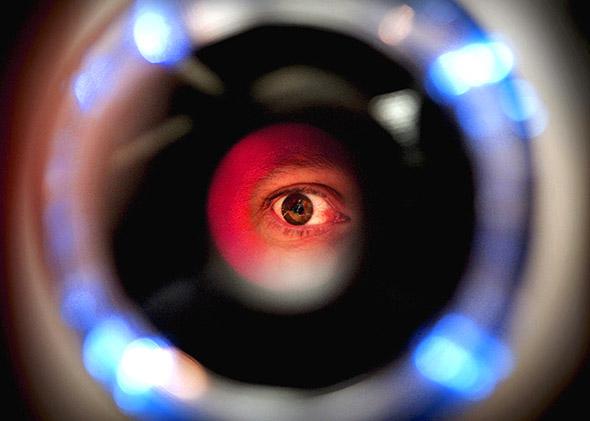

The biometric scanners we see in Hollywood spy thrillers such as Mission: Impossible all look so high-tech and capable—eye scanners, fingerprint readers, and facial-recognition systems that perfectly distinguish friend from foe. With press like this, it is easy to understand why people think biometric authentication systems are impossible to defeat and are hailing them the future of identity, security, and authentication.

Indeed, Gartner, a technology research firm, estimates that 30 percent of companies will be using biometric identification on their employees by 2016. Already gym-goers at 24 Hour Fitness locations are encouraged to use their fingerprints for identification at the chain’s clubs, while patients at New York University’s medical center needn’t carry their insurance cards anymore, because the hospital has enrolled more than 125,000 individuals in its PatientSecure system, which uses a specialized biometric scanner to measure the unique vein patterns in the palm of the hand as the primary means of identification.

To be fair, biometric security will offer many advantages; while you may forget your password or driver’s license, you’ll always have your fingerprints on you, and in many ways it’s a vast improvement from the feeble alphanumeric characters we use as passwords today.

But, as it turns out, biometrics are not as safe or foolproof as you might believe.

Today if you are one of the tens of millions of victims affected by identity theft, it is possible to get a new credit card or even Social Security number. If your Facebook or bank account is hacked, you can reset your password. But when your fingerprints are stolen, there is no reset. They are permanent identification markers, and one snagged by hackers is out of your control forever. When your gym, mobile phone company, and doctor all have your biometric details and those systems become hacked—as they undoubtedly will—remediation of the problem will prove much more difficult, if not impossible.

In other words, if the future of identity is all about biometrics, then the future of identity theft will involve stealing and compromising biometrics, and thieves and scammers are already hard at work circumventing these systems. To demonstrate this threat, Tsutomu Matsumoto, a security researcher at Yokohama National University, has devised a method allowing him to “take a photograph of a latent fingerprint (on a wineglass, for example)” and re-create it in molded gelatin. The technique is good enough to fool biometric scanners 80 percent of the time. Hackers have also used everyday child’s Play-Doh to create fingerprint molds good enough to fool 90 percent of fingerprint readers.

Still, governments and businesses are trying to persuade the public of the superior safety and security offered by biometrics. In Germany in 2008, a public debate erupted over the issue when the country’s chief cop and interior minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, began strongly advocating for the greater use of fingerprint biometrics. In response, a hacker group known as the Chaos Computer Club lifted the minister’s fingerprint off a water glass that he had left behind after delivering a public speech at a local university. The hackers then successfully copied the print and reproduced it in molded plastic—4,000 times. The replica prints were distributed as a special insert in the club’s hacker magazine along with an article encouraging readers to use the print to impersonate the minister, opening the door to planting his fingerprints at crime scenes.

Proponents of biometric security also argue it is inherently more secure because fingerprints are an immutable physical attribute that can’t be altered by criminals. Well, turns out, that’s not true either, as the 27-year-old Chinese national Lin Ring proved in 2009. Lin paid doctors in China $14,600 to change her fingerprints so that she could bypass the biometric sensors used in Japan’s airports by immigration authorities. In order to sneak back in, she paid Chinese surgeons to swap the fingerprints from her right and left hands, having her finger pads regrafted onto the opposite hands. The ploy worked, and she was successfully admitted. It was only weeks later, when she attempted to marry a 55-year-old Japanese man, that authorities noticed the odd scarring on her fingertips. Japanese police report that doctors in China have created a thriving business in biometric surgery and that Lin was the ninth person they had arrested that year for surgically medicated biometric fraud.

Needless to say, such draconian measures would not be necessary if hackers could merely intercept the fingerprint data from the Internet of Things–enabled biometric scanner as it was sent to the computer server for processing—something the security researcher Matt Lewis has already demonstrated at the Black Hat hacker conference in Europe. Lewis created the first-ever Biologger, the equivalent of a malware keystroke logger, which, rather than capturing all the keystrokes somebody innocently typed on her computer, could effectively steal all the fingerprint scans processed on an infected scanner. Lewis demonstrated that his biologging device allowed him to analyze and reuse the data he had captured to undermine biometric systems, granting access to supposedly “secure buildings.” While it is tempting to believe that biometric authentication is inherently more impenetrable than legacy password systems, the assumption only holds true if the new systems are actually implemented in a more secure fashion. Otherwise, it’s just old wine in a new bottle.

The same holds true for facial recognition technologies, which have improved their match rates significantly and now can approach 98 percent accuracy. Today there are even systems that can match your face to your Facebook profile within 60 seconds as you walk down the street and derive your Social Security number 60 seconds later. But these developments are surely not without their problems. Just as fingerprint sensors can be hacked, so too can face-printing systems increasingly be used to unlock your phone or computer or to gain access to your office. All it takes to defeat some systems, such as those on Lenovo laptops or smartphone password apps such as FastAccess Anywhere, is to hold up a photograph of the person you wish to impersonate. This very technique has also worked with iris scanning, allowing hackers to reverse engineer the biometric information stored in a secure database and use it to print a photographic iris good enough to fool most commercial eye scanners.

There is also another category of biometrics known as behavioral biometrics, or behaviometrics, which measures the ways in which we and our bodies individually perform or behave, traits that can be just as revealing as human fingerprints. Our keyboard typing rhythms, voices, gait and walking patterns, brain waves, and heartbeats can be quantified in ways that provide unique signatures that singly identify us. Just as anatomical biometrics are being used more frequently for security, identification, and access control, so too will the growing field of behaviometrics; in fact, it is already happening.

Voice biometrics are being used by companies and call centers around the world to uniquely voice print customers. That recording you hear when on hold telling you that “your call may be recorded for quality assurance purposes” fails to disclose the fact that one of the ways companies are measuring call satisfaction is by the tone, tenor, and vocabulary you use during your call. Moreover, in an effort to fight fraud, companies are building vast recorded-voice databases of consumers, generating unique voice prints that can be used in future calls to ensure the person on the line matches the original biometric vocal print taken. If the voices don’t match, callers are asked further verification questions in a process that is completely nontransparent to the general public.

Companies such as the online education platform Coursera use keystroke recognition to ensure the same student “attends” each virtual class before issuing a certificate of completion. Watchful Software’s TypeWatch product is designed to run on networks in the background to constantly monitor a user’s typing rhythms to uncover and block attempts at unauthorized access. Other firms such as the Sweden-based Behaviometrics AB have created tools that note how each mobile phone or tablet user holds his phone, at what angle, the way he types on the virtual keyboard, and even how he swipes and pinches the screen, revealing minute millisecond pauses between various actions. Any variation from an established “cognitive footprint” will set off alarm bells at a bank and block access to the account, one of the reasons Denmark’s largest bank, Danske Bank, adopted the technology.

If these technologies seem intrusive now, the reality is that they may well be even more so in the future. Already Motorola has partnered with the firm MC10 to “extend human capabilities through virtually invisible wearable electronic RFID tattoos” that can be used for password authentication, while Proteus Digital Health has created a pill that you can swallow and is powered by the acid in your stomach to create a unique 18-bit signal in your body to turn your entire person into an authentication token.

Though many of these biometric security products offer great promise, hackers and criminals will not just give up their self-enriching efforts and go home defeated. Instead, given the growing ubiquity of finger sensors, facial-recognition software, and behaviometric technologies, we can fully expect criminals to adopt these tools and use them to their full advantage. When they do, they won’t just be hacking our computers. They will be hacking the Internet of You.

Copyright 2015 Marc Goodman. From Future Crimes: Everything Is Connected, Everyone Is Vulnerable, and What We Can Do About It. Reprinted with permission from Doubleday, a division of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.