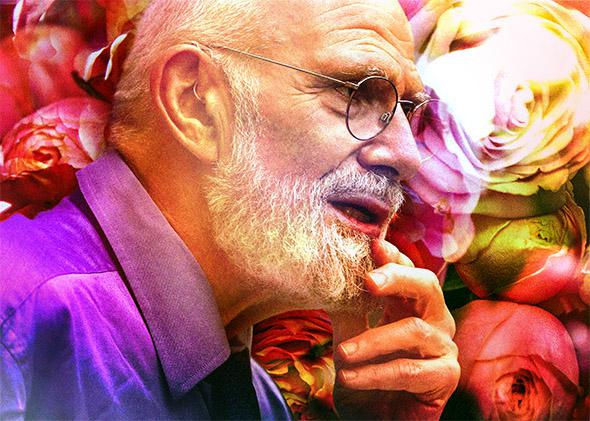

I woke up last Thursday to sad news in my Facebook feed. Oliver Sacks, a neurologist and prolific author whose work I had admired for years, had announced his own impending death in the New York Times. Few writers have accounted for the fragility of human life more richly, eloquently, and fully than Sacks. It came as little surprise, then, that when he turned to his own mortality he did so with uncommon grace. Nor was it surprising to find my friends sharing his story: Sacks’ work—which explores the ways that we see, hear, and think from every possible angle—had touched many of them in just as many ways.

I was struck, however, by the tone of uplift that resonated throughout my friends’ responses to the article. Those I spoke to gave a variety of reasons to explain why they’d shared the piece, from an interest in Sacks’ scientific work to the article’s resonance with their own artistic endeavors. Despite their differences, the language with which they introduced the article was strikingly similar. Only a few referred to it as sad, though I imagine many of them thought it was. Instead, they spoke of it as “inspiring,” “beautiful,” and “moving.” I suspect they were referring primarily to the essay’s closing paragraphs, paragraphs that many of them also quoted, in which Sacks speaks of his gratitude for the life he has lived, and of his happiness at loving and being loved.

How many of my friends would have shared the story if Sacks had failed to take that final turn, if he had described the cells multiplying within, but not his love for the world without? To be clear, I would never fault people for celebrating Sacks’ essay—it is just as inspiring, beautiful, and moving as they say. Nevertheless, the article’s popularity speaks to a troubling trend: Facebook’s culture of the like is actively making it harder to express negative thoughts and feelings.

Much has been made of the tyranny of the “like” button. Flavorwire’s Tom Hawking, for example, worries that it enforces positivity, rendering it difficult for us to respond to grimmer posts, while others have quit using the feature altogether. For similar reasons, Facebook itself is sometimes rumored to be considering a “sympathize” button that would allow users to facilely acknowledge the pain of others. Such accounts focus primarily on the ways we process what the site sets before us. More importantly, though, our longing for likes, and our knowledge of these difficulties, may be changing the way we compose sad posts in the first place.

When I was diagnosed with papillary thyroid cancer last June, I almost immediately decided to let my illness play out in public. On my blog, I sought to write unapologetically about my experience of disease, charting the shape of my anger and discussing my fear of loss. But when I took to Facebook to publicize my work, I found that I was censoring myself. Afraid of writing something that would be literally unlikable, I emphasized positive developments in my health or quoted passages from my writing that had nothing to do with sickness. Though I still felt what I felt, Facebook had changed the way I sought the attention of my loved ones, crowding out my negative thoughts in favor of cheerier ones.

Surely you’ve seen examples of this phenomenon in your own feed. When friends’ parents die, for example, they’ll often post pictures of the deceased in happier days, days when they were at their most beautiful. With these images, they give us permission to like the sad stories that run below. Here, as in the case of Sacks’ somber announcement, the sad is shareable only on the condition that it mask part of itself. Facebook allows us to be public about our sorrows, but to be heard they must sound some joyous note.

Research suggests that social media is uncommonly good at making us miserable. The irony may be that Facebook itself is also making us more reluctant to voice that misery. A study conducted by the Pew Research Center indicates that Facebook users are slightly less likely to be aware of stressful events in the lives of others than users of most other social technologies. It seems probable that the site’s subtle cultivation of positive thinking accounts for this gap. Searching for likes, we are less willing to discuss our own traumatic experiences. And because we primarily see posts that others have already liked, we encounter others’ traumas less frequently.

Facebook, of course, is not solely responsible for the reticence of its users. The psychotherapist Stephen L. Salter, who has written on what he calls “the tyrannical culture of positivity,” explains that his clients sometimes hesitate before bringing up negative information. “Some people are not sure how much of themselves they can actually be, how much I can take,” he tells me. Even when they acknowledge depression in therapy, they rarely speak of it more widely, reluctant, Salter says, to “burden other people” with their feelings.

Pew’s recent study of social media suggests that we may not be wrong to predict such effects. It concludes that while social media can decrease stress, it can also increase it in those who are exposed to “undesirable events” in the lives of others. Withholding negative information, then, constitutes a kind of anticipatory empathy for the empathetic, an attempt to keep others from feeling the things that we feel. Here, silence transforms into a misguided form of care, an attempt to aid others when we most need to aid ourselves. The savvier we get to Facebook’s structures—to the mechanics of its algorithms and the best ways to collect likes—the more inclined we become to swallow our ugly feelings, thereby intensifying this unfortunate bind.

I don’t intend to suggest that Facebook users should share every grim detail of their lives, as some commenters have suggested. But insofar as we already live in a culture of confession—ours is still the Age of Oprah, after all—we must think carefully about the ways we reach out to one another. The fact that Facebook recently had to revise its policies on the pages of the deceased is evidence that the site has become central to the ways that we grieve. Facebook likewise plays an important role in all of our states of feeling, especially those that most urgently put us in need of one another.

In a recent article in the New Republic, Phoebe Maltz Bovy argues that undersharing has now become a bigger crime than oversharing. In our contemporary climate, she writes, “Social-media silence, once viewed as admirable discretion … now seems suspect.” Ultimately, however, the important thing may be that we’re sharing things at all. So long as we’re determined to speak publicly about our private lives, we should do so clearly and honestly. It’s not that we should go negative when we go online, only that we should ensure others can if they must. What good are our social networks if they can’t lift us up when we fall?

Sometimes I’ll press the like button even when the news I read is bad, press it as if to say, I’m glad that you cared enough to share this with us. I’m glad that you invited us to listen. I’m certainly not the first to express such gratitude: Near the end of his life, Oscar Wilde wrote that he no longer craved pleasure. In a letter written from prison to a former lover, he claimed that he would not mind if a friend failed to invite him to a feast. “But if,” he explained, “after I am free a friend of mine had a sorrow and refused to allow me to share it, I should feel it most bitterly.”

Having faced the worst, Wilde longed only to ease the suffering of his compatriots. We cannot know the true loveliness of the world, he thought, until we face the unvarnished fact of its sorrows. This is the lesson of Sacks’ essay, too, and we do it a disservice if we only admire it for its likable conclusion.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.