It isn’t that anyone expected Barbie to be a role model for aspiring engineers. Maybe that’s why Computer Engineer Barbie’s appearance on shelves a few years ago was so exciting—because it was unexpected. Girls consistently see more men than women as scientists in the media, and Barbie’s more than 100 career choices haven’t exactly leaned toward STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) disciplines, though Wikipedia lists architect, astronaut, paleontologist, and SeaWorld trainer along with computer engineer. So this Barbie was a rare opportunity. Imagine young girls playing out stories of Barbie as a Web developer, database administrator, software engineer, or game designer! No one ever told me that I could play “computer science Ph.D. student” with my Barbies, though to be fair, this was the ’80s and the pinnacle of computing for me was Oregon Trail.

So this week, when a book associated with Computer Engineer Barbie went viral, the overwhelming response I saw was disappointment.

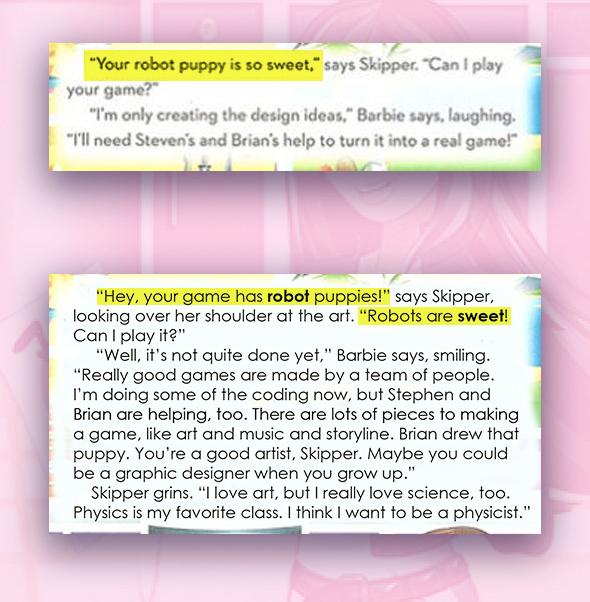

In the book, Skipper asks if she can play a video game that she thinks Barbie is making. “I’m only creating the design ideas,” Barbie says, laughing. “I’ll need Steven and Brian’s help to turn it into a real game!” The problem with Barbie’s narrative in the book isn’t that she is depicted as “only” a designer; it is the assumption that she is the designer, despite the title billing her as the “engineer.” The message this sends is: Sure, girls can work with computers—but obviously they aren’t the ones doing the coding. Programming is for boys and art is for girls. After all, as the 1992 “Teen Talk Barbie” expressed, “Math class is tough!” (Or, as Malibu Stacy said, breaking Lisa Simpson’s heart: “Don’t ask me, I’m just a girl!”)

Courtesy of Casey Fiesler

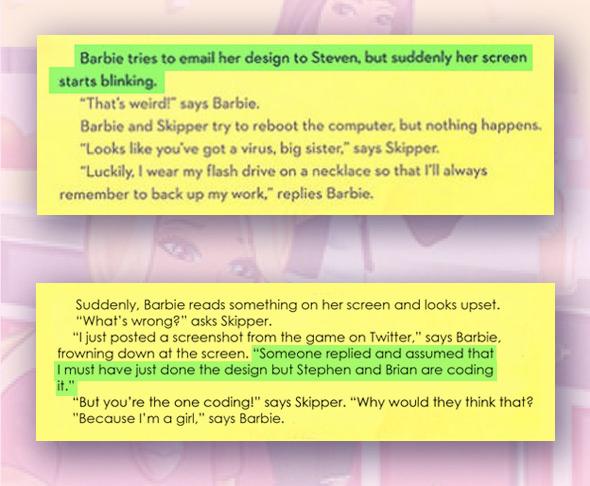

It isn’t that Barbie needs to be the world’s best programmer, or develop the game by herself, but in the book she comes across as completely incompetent when it comes to computers. She not only inadvertently infects her own computer with a virus, but she infects Skipper’s as well—and then she requires Steven and Brian’s help to fix the problem. On the bright side, Barbie’s computer science teacher is a woman, though this positive aspect is overshadowed by what overwhelming criticism called pervasive sexism in the book. In addition to disappointment, a large part of the reaction was shock: Is this really how a girl in STEM is being represented in this decade?

Courtesy of Casey Fiesler

If Barbie fans reading the book were wondering what it really meant to be a computer engineer, the only answer seemed to be “something to do with computer viruses” or maybe “getting a boy to help you.” The story spread quickly in my social network of computing academics, where we are all too aware of the problem of underrepresentation of women in computer science. While this single book may not seem like a big deal, it is simply one more example of this much larger issue. So I decided to fix it—or, rather, remix it—and create a story about Barbie as a computer engineer (or more accurately, a computer scientist or a software engineer) that doesn’t embrace those stereotypes. You can find the book below.

I happen to study the art and law of remixing; my dissertation focuses on the role of copyright in online creative communities and I’m on the legal committee for the Organization for Transformative Works. One of the things that I love about remix is the opportunity to transform a narrative. The doctrine of fair use in U.S. copyright law allows for just this kind of critical and creative expression—where, if you think that Twilight is anti-feminist, you can create a world in which Buffy stakes Edward. One of my first thoughts upon seeing the reaction to the Barbie book was that a positive outcome would be the inevitable remixes and memes that would result. So … why wait? Having spent the day reading commentary from other computer scientists, I thought I knew how our community would want to change the narrative.

Giving Barbie more agency was the first order of business, as well as taking out her incompetence. Now, rather than being upset about a virus, she is upset about discovering sexist attitudes toward her role as a programmer. Something else that was important for me to express is that there is nothing wrong with being the designer. In fact, though I know how to code, it isn’t something that I do much of in my current role as a computer scientist. Sometimes, this part of the field is delegitimized, which is particularly problematic since there do tend to be more women in computing subfields such as human-computer interaction, social computing, or design. There is more to computer science than just programming, and I would actually love to see a Barbie: I Can Be an Interaction Designer book as well. But for Barbie being a computer engineer, I wanted to see her doing the programming—with Steven and Brian (as the designer) working alongside her. Also, it’s OK for Barbie to be feminine and to be a coder, if that’s who she is. And it’s OK for Steven to like pink, too!

In my department (the School of Interactive Computing at Georgia Tech), the gender distribution is much more balanced than you typically see in computing, which is perhaps why I haven’t experienced sexism on anywhere near the scale as some of my female colleagues who are in traditional computer science departments or who work in industry. But it still happens. Earlier this year when my research received some media attention, I was presumed male in an article. Though my first name is gender-ambiguous, it would take a two-second search to find out that I’m not a “he”; I can only assume that the journalist saw “computer scientist at Georgia Tech,” and it didn’t occur to him that I might be a woman. These are the kinds of assumptions that narratives like the Barbie book propagate.

When I created the remix, I did it mostly as a cathartic exercise, and to share with other computer scientists in my community. I never expected it to get nearly as much attention as it has. Despite my fear that there might be some negativity (there has also been a lot of discussion in our community about Gamergate lately), the response has been 99 percent positive. So many people care about the issue of representation of women in science. I have gotten so many comments, tweets, and emails from people telling me that they are reading my version to their children. And after a few days of controversy, Mattel not only apologized but pulled the book from Amazon. In 1992 after the complaints about Teen Talk Barbie (“Math class is tough!”), Mattel replaced the doll with one that didn’t say that phrase. Maybe now they’ll commission a new computer engineer book that provides a more positive role model for girls. In the meantime, you could make one yourself! Someone else created Feminist Hacker Barbie to generate your own book pages. Or feel free to remix my remix—I licensed it under Creative Commons.

In the end, we don’t need a book (or a doll!) to show a young girl that STEM is just as much for them as for boys. Tell her, or show her! Find out what she’s interested in and tell her how technology relates to it. Point out that computers aren’t just passive by getting her started in a kid-friendly programming environment like Scratch. Or maybe just hold up any Barbie say, “What if she’s a computer engineer this time?” And then explain to her all of the cool work that Barbie does with computers—without needing Steven and Brian’s help.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.