Your parents dated the way Warren Buffett picks a stock: a close review of the prospectus over dinner, careful analysis of long-term growth potential, detailed real asset evaluation.

Sure, the old economy dating market in which they participated had the occasional speculative frenzy: Woodstock, V-E day, whatever went on at Studio 54. My parents met during spring break. In Florida.

But love and its compounding interests were usually pursued with appropriate due diligence.

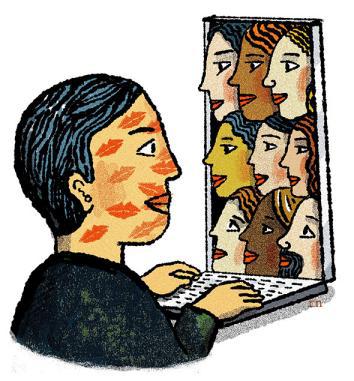

Then came the Internet. The “innovation” that has driven the financial industry over the last two decades has also transformed the dating market, with similar effects on romance as on the economy. The traditional focus on long-term security—marriage and retirement—has been replaced by a relentless pursuit of instant gratification and immediate returns. These days, the Wolf is as much on Tinder as on Wall Street.

Just look at what online dating has done to the meet market. The speed and frequency of transactions has gone up. Volatility has spiked as relationship investment strategy has changed from building long-term value to quarterly—or nightly—profits. New investors have entered the market with greater ease, although all too often only to be taken advantage of by more sophisticated players. New avenues for fraud have opened up: Manti Te’o meet Bernie Madoff on Ashley Madison. Even inequality has risen. Some investors are rolling in it; others have just lost their shirts.

How did the bedroom end up looking so much like the boardroom?

In successive waves, innovation pioneered in the financial markets has been adopted to dating. Online dating’s initial trading platforms—Match created in 1995, JDate in 1997, etc.—were the relationship equivalent to the online trading sites that first allowed investors to directly manage their own portfolios. Think “Talk to Chuck,” except if he can message you first (hopefully not about the size of his portfolio).

Then came quantitative trading. EHarmony’s “scientific approach” came out in 2000, with later editions augmented by an “algorithm of love.” OkCupid, launched in 2004, has brought us big-data dating. The site captures a “datacylsm” of online behavior to be romanticized—and monetized.

And sure enough, as in finance, quants soon turned to data-driven approaches to skew the market to their advantage. Slate contributor Amy Webb “hacked” OkCupid using an algorithm to eventually find love.

Then came high-frequency trading. Sites like Grindr, launched in 2009, or Tinder, launched in 2012, give a whole new meaning to what Michael Lewis has described as “flash boys” in the financial markets. We now swipe left or right so quickly that we can’t even fully process the transactions—in this case, people—flashing across our screens.

Online daters are also mirroring the move away from vanilla investments to more exotic or niche offerings.

In the old days, you could easily invest only in broad categories of assets: stocks, treasuries, major international markets. Nowadays, everyone can easily pursue his or her own 50 shades of investment strategy. Want to invest in New Zealand wool? Click here. Looking for a furrymate? Try here.

To be clear, I make no judgment against adults consensually engaging with other adults—whether in the marketplace or in their private lives. The transformation accompanying digital dating has been complex. It has brought both new opportunities and new risks.

On the positive side, online dating has offered broader opportunities. It has created, in effect, a more efficient market—connecting people with shared interests who may have never otherwise found each other. It has also helped “level the romantic playing field”—destroying old monopolies such as the traditional firstmover advantage men had over women in asking someone out.

Its success speaks for itself: More than one-third of new marriages now start online.

Yet, more opportunity has also often meant less stability. The new dating economy—like the new economy itself—has left many participants feeling like disposable commodities in this most naked form of capitalism.

Innovation, likewise, affects even those who hope to avoid it. Dating is no different. The market dynamics of dating, including for those who don’t date online, has been transformed in the same way that financial innovation has changed the environment for all firms: You’re forced to keep up with the latest trends or risk losing out on the market entirely (cue the New York Times on “girls and hookup culture”).

And even if you embrace online dating, it’s hard not to feel like something has been lost—that we’re losing our sense of touch for a pixelated version of romance or pseudoromance. We may be falling in love with Her, but who exactly is she? And how many other people are we all talking to?

It increasingly feels like things may be spiraling out of control.

Is the crisis of capitalism going to morph into a crisis of coupling? Perhaps this crash will also start with its own version of a housing collapse. Potentially risky ventures that threaten wider contagion may now be on the rise. Take wife swapping, for instance, now greatly facilitated by sites like—wait for it—wifeswapping.com. Is this the sexual equivalent of a credit-default swap? I suppose the practice can create enormous shortterm returns for some. But when the crash comes, participants seem to not only risk losing their homes; they may not even be sure what they—or their counterparties—are left holding.

Money addiction and sex addiction also seem to be on the rise. It’s karmic genius that Anthony Weiner left Congress to run for mayor of New York. Washington and Wall Street, after all, are in bed together in more ways than one.

Or perhaps the crisis is not fundamentally about technology. Maybe we’re just reacting to the divorce boom of our parents and grandparents’ generation. Deregulation of the financial markets also began with a breakup: the divorce of Glass and Steagall in the late 1990s. (The breakup of their union—the Glass–Steagall Act, aka the Banking Act of 1933—allowed commercial banks to get in bed with securities firms, an affair often credited as a major cause of the financial crisis.)

Whatever the specifics may be, there is no going back. The question now—in the economy and in our dating lives—is how to best share the benefits of innovation while managing its negative effects.

Here once again, dating is attempting to learn from the financial industry.

There’s been a new wave of apps that seek, with varying degrees of success, to borrow economic principles from the broader marketplace. Lulu has designed a ratings agency for women to rate men. One company is attempting to perform arbitrage, ferrying singles between San Francisco and New York. Hinge—inspired by the proliferation of trust-based applications in the shared economy like Airbnb—has built a trust-based dating app, where singles are matched through links with mutual friends. Next thing you’re going to know someone is going to develop an app that can predict if there is a bear market in the bear market.

As long as the essential human lust for love—and love of lust—remains, the market for an ever more exact accounting of the heart will continue to expand. At the end of the day, we all just want someone to invest in us.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.