Passwords are a hassle.

Some are hard to remember. Others are easy to guess. And if you use the same one for every site, you’re asking for trouble.

That’s clearer than ever after the New York Times reported this week that a Russian hacker group has managed to compile a database of some 1.2 billion stolen username-password combinations. If they just nabbed, say, your LinkedIn credentials, it’s probably not a huge deal. But if you use the same email and password for sites like PayPal, Amazon, or Gmail, look out.

On the other hand, using a different password for every site can be a headache, especially since the requirements for length and special characters vary from one to the next. Some services force you to come up with a fresh password every few months. Throw in two-factor authentication—which you really should be using, at least for your more sensitive accounts—and you could spend a good chunk of any given day just trying to log into things.

No wonder forward-thinking techies have been calling for years for the death of the password. Microsoft’s Bill Gates has been predicting their demise since 2004. “Kill the password,” urged Wired’s Mat Honan in 2012. Some are now convinced the end is at hand. “The password is finally dying,” Christopher Mims declared in the Wall Street Journal in July.

Let’s be careful what we wish for.

The problems with the password as a security system are easy to see. It’s only when you take a hard look at the alternatives that its subtle virtues become apparent.

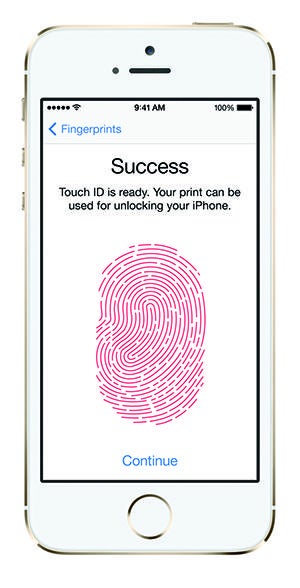

Take biometric authentication systems, like fingerprints, iris scans, voice recognition, or even keystroke dynamics. Part of their appeal is that they rely on physical features unique to every individual. Hackers can’t guess your fingerprint, and you can’t misplace or forget it. In theory, then, you could use the same method of authentication for every service. It would all be so seamless—just touch, look into, or speak into a sensor, and you’re in.

That glorious simplicity, however, comes at the cost of flexibility—and, potentially, privacy and anonymity as well.

The first inconvenience of biometric authentication is that it requires special hardware and software. Smartphones and tablets are beginning to add fingerprint sensors as a standard feature, which will help. But it will be years before everyone has one. And it could be years after that before everyone manages to agree on interoperability standards so that you can use the same device to log in to any site.

A second problem is that biometrics are inherently imperfect. Passwords are either right or wrong. But biometric sensors require a certain level of tolerance, because you aren’t going to touch the sensor, look at the camera, or address the microphone the same way every time. Too little tolerance and you’ll get a lot of false negatives. Too much and you’re prone to false positives, as when hackers fooled Apple’s Touch ID sensor less than 48 hours after the iPhone 5S was released. Anywhere in the middle and you’ll end up with some of both.

Photo courtesy Apple

Which leads us to the third problem with biometrics: their permanence. If someone steals your password, you can reset it with a few clicks. If someone manages to spoof your biometric signature, you can’t just request a new one.

What’s nice about biometrics is that you don’t need to use a different credential for every site. What’s scary is that you can’t use a different credential for every site—your fingerprint is the same everywhere you go. That means you’re verifying your true identity with each login. No more claiming your Twitter was hacked if you post something embarrassing.

Other popular alternatives to the password come with similar drawbacks. In the WSJ, Mims made the case for device-based authentication, in which you receive fresh credentials for each login on a device like your smartphone. For instance, Google could shoot you a text message with a randomly generated six-digit code every time you wanted to log in to Gmail.

Codes sent to your phone are becoming increasingly popular as a complement to passwords in two-factor authentication systems. In that capacity, they work quite well. But Mims thinks we could do without the password altogether. Authentication via text message, he says, “is so much better than a password alone that, in a sense, it makes the password obsolete.”

But ditching one single-factor system (passwords) for another (device-based authentication) just pushes our security problems around. You may be less likely to lose your phone than your password, but when you do, it will be like losing all your passwords at once. Mims notes that you can easily lock or even remotely wipe your phone if someone steals it. But how do you log in to the service that lets you do that? With a password.

Irksome as it is to create and remember different usernames and passwords for different sites, it allows for forms of privacy and anonymity that more streamlined solutions can’t. The ability to set up different credentials for different sites allows you to maintain separate online identities, which even Mark Zuckerberg now acknowledges can be a good thing.

The nature of security is that there is never a single perfect solution. Medieval fortresses needed walls, moats, and archers. Maximum-security prisons have fences, alarms, informants, and guards. Likewise, fingerprints and text messages will take their place alongside passwords in the robust personal security systems of the near future, but they won’t kill the password—and they shouldn’t.

That said, not every prison is maximum-security, and not every app or website needs multiple layers of authentication. If you want a modicum of security without driving yourself insane, set up two-factor authentication on a few key services—like your primary email and your online bank account—and give each a strong, unique password that you’ve committed to memory. For everything else, either use a password manager or set up a simple mnemonic system like the one my former colleague Farhad Manjoo recommended a couple of years ago.

Passwords, you see, are the worst possible security system—except for all the others.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.