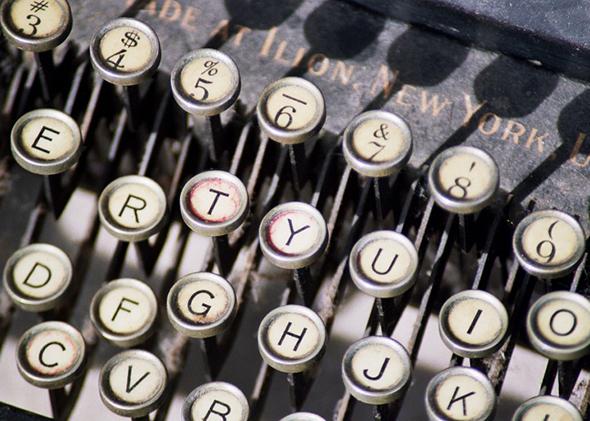

If the National Security Agency can get access to any computer it likes, then maybe it’s time to stop using computers to store state secrets. That seems to be the logic behind last week’s admission by German politician Patrick Sensburg that Germany has contemplated using typewriters to compose sensitive documents in the wake of the revelations by Edward Snowden last year.

During a July 14 interview on the Morgenmagazin TV show, Sensburg, who is leading the Bundestag’s parliamentary inquiry into NSA espionage in Germany, was asked whether he had considered using typewriters to foil international espionage efforts and replied, “As a matter of fact, we have—and not electronic models either.”

“Really?” asked the interviewer. Sensburg confirmed: “Yes, no joke.”

And why should it be a joke? I’ve long believed that the safest place to store a secret is in a notebook in a locked box under your bed. There’s something to be said for taking the most sensitive and secret information as far offline as you can.

For all that it may seem ludicrous to imagine high-level government operatives tapping away at mechanical machines from the 1920s, they could do worse. In fact, Germany is not the first country to consider such a step backward in time—a Russian security agency purchased about $13,000 worth of electric typewriters soon after Snowden’s initial leaks.

Typewriters potentially serve two purposes for governments concerned about the Snowden leaks. For one, the old-fashioned machines that Grandma wrote on back before word processors render the high-tech interception and espionage techniques detailed in the leaked documents entirely useless. But typewritten documents can also help governments guard against their own internal leaks because each machine has a distinct typing pattern, or signature, that makes it possible to identify which device any document was written on. In other words, a leaked memo composed on a typewriter could be traced back to a specific machine, potentially making it easier to identify its source.

Of course, typewriting—or even handwriting—secrets does not preclude espionage. Countries were spying on one another back when secret messages were written on papyrus, and while a return to older technology cuts off some modes of access that can be exploited by spies, those quaint manual Olivettis have their own vulnerabilities. The NSA’s sophisticated man-in-the-middle attacks may be useless when it comes to intercepting typewritten documents, but physical printed pages mean that real live men in the middle—people delivering the messages—may be able to catch a glimpse of any secrets.

A return to more old-fashioned modes of communication would likely herald a return to more old-fashioned modes of espionage. If countries decide to revert to using typewriters for top-secret information, then intelligence agencies will have to rely more heavily on human intelligence tactics than signals intelligence. So what is really to be gained from purchasing a typewriter or two?

Human intelligence efforts, such as the U.S. installing a person in the German government to intercept typewritten memos, are considerably more difficult to scale up and execute en masse than signals intelligence operations. And the scale of computer-based espionage is part of what makes it so much more alarming than those Le Carré Cold War moles and double agents. Sure, typewriters can still be spied on—but some countries may feel more able to understand and match that variety of espionage, and not entirely without reason.

A full-scale return to the precomputing era is obviously preposterous, but government agencies might do well to keep their most highly sensitive information off computers entirely. Already, many government (and nongovernment) facilities dealing with top-secret information “air gap” their machines, disconnecting them from the outside Internet. But even an air-gapped computer, or computer network, can be infiltrated by means of infected physical media (USB sticks, for instance, or software installation CDs). Take away all the network connections and physical media ports, on top of Internet connectivity, and you’re basically left with a glorified typewriter—a machine you can type on, but can’t move data onto or off.

Typewriters may be the last word in air-gapped technology, but they don’t seem to have won over many supporters in Germany. The Guardian reports that another German politician, Christian Flisek, told Spiegel Online: “This call for mechanical typewriters is making our work sound ridiculous. We live in the 21st century, where many people communicate predominantly by digital means. Effective counter-espionage works digitally too. The idea that we can protect people from surveillance by dragging them back to the typewriter is absurd.”

Flisek is right to point out that many of our modern-day security measures depend on computers—advanced encryption is simply not possible on a typewriter. But it’s not clear that these digital means of counterespionage are more effective than earlier efforts. If anything, the Snowden revelations seem to suggest that the digital age has advantaged the spies more than it has the people they spy on.

At the end of the day, of course, most of us are not going to stop using computers. Even most government officials and intelligence officers aren’t going to stop using computers. Perhaps a typewriter could come in handy for writing a few very sensitive memos here and there, but older communications technologies—like older espionage tactics—don’t scale up to the demands of the present day.

So there’s no point in running away from the challenges of cybersecurity in the direction of the nearest antique shop. Those challenges need to be addressed, and talk of typewriters (or carrier pigeons) should not under any circumstances detract from or diminish the urgency of that larger goal. Installing typewriters would be a mere Band-Aid in the larger context of figuring out how to protect information.

But there’s also no reason why a partial, targeted return to older technologies couldn’t be coupled with serious efforts to improve the security of newer ones. Even a government that devoted considerable time and energy to protecting its computer networks might be justified in feeling that some information was still too sensitive to be stored on them. Trying to turn back time won’t come close to solving anyone’s security problems, but there’s a place for predigital technologies in even the most modern security calculations. As for governments without the cash to spare on the technology of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they can always go back a few more centuries still—to pens and paper.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.