“You are pitiful, isolated individuals!” Leon Trotsky shouted at the Mensheviks as they exited the Petrograd Second Congress of Soviets in 1917: “You are bankrupts. Your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on—the dustbin of history!”

Sixty-five years later, Ronald Reagan turned those words on Trotsky’s life’s work by pronouncing from the stage of the British Parliament that Soviet communism will be left on “the ash heap of history.” And just 19 years later the squalling Muammar Qaddafi screamed that the 2011 enforcement of a Libyan no-fly zone was perpetrated “by a bunch of fascists who will end up on the dustbin of history.”

While these outraged boys were squabbling, they missed the point—the dustbin is history. The midden, the shell heap, the garbage dump, the junkyard—these are often our most fecund sources of raw material for understanding past civilizations. Archaeologists shout “Eureka!” when they turn over a shovel and realize they are digging in the scrap pile of the civilization they are tracing. More has been learned about humanity by what we’ve thrown out than by what we’ve privileged as our monuments to posterity.

Courtesy John Dahlsen/Anchorage Museum

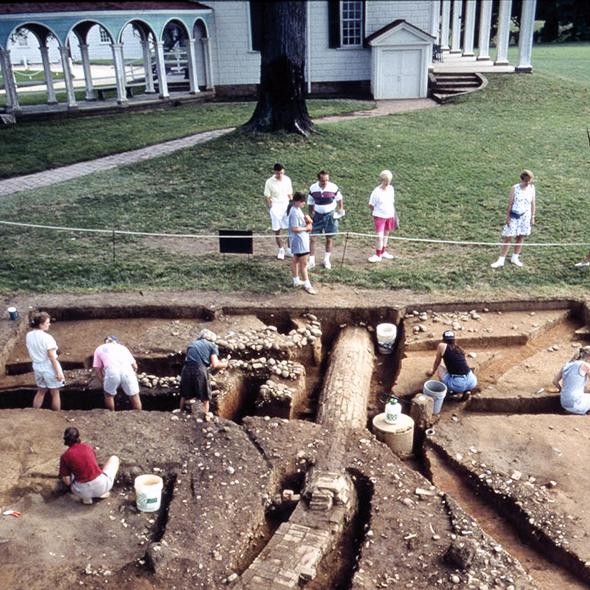

It is precisely because we do not polish and pretty-up what we throw away that simple materials, used and discarded, carry such intimate and revealing insights into who we are. The mindlessness of tossing something on the heap removes any trace of a curated historical record and provides access into the unconscious soul of the civilization that disposed of it. The Pyramids of Giza, Teotihuacán, the Coliseum—all these built sites are a kind of bombast and braggadocio to each era. But if you want to know who people really were, if you want to know the texture of their lives, then look at what they threw away. The Mount Vernon Midden (now alive again with its own interactive website) has told us far more about George Washington than his monument. As any savvy cultural reporter knows: follow the midden.

Photo courtesy Mount Vernon Midden

So if the dustbins of history provide irrepressible insights into cultures gone by, why wouldn’t our own refuse tell as much about us today? It does, and we have the investigative power of artists to do that work and make that point. If who we are is best shown to us by the crap we toss and the way we do it, somebody has to assemble those pieces so we can see them, understand what it means and recognize ourselves in those reflections from the dump. To change our future, we need to understand our garbage and change what we throw away and why we do it.

Artist and curator Garth Johnson, in his recent TED talk “Recycling Sucks,” reminds us that of the “three R’s”—reduce, reuse, recycle—recycle is the least effective solution. Then he asks a further question: What glories have we lost to recycling? How many sublime Greek bronzes were melted down and repurposed as helmets and weapons? What can be learned about our values by what we deem to be disposable and then beat into swords?

Artist Miguel Angel Rios inspects a discarded baby doll at a dump in Mexico.

Photo courtesy Miguel Angel Rios

Just as an unfiltered examination of the refuse of the past serves as a means of learning about societies past, artists looking at the garbage of today reveal telling and deep secrets about ourselves today. For instance, Melanie Smith—a Mexico-based artist—films while spiraling above the single, massive garbage dump for Mexico City. Her work invokes Robert Smithson’s monumental Spiral Jetty while investigating garbage to reveal how society functions. Miguel Angel Rios’ videos carry this forward: He reveals a labyrinth of alternative realities and complex subcultures developing and growing within the ignored yet massive ecologies of the Mexico City and Oaxaca dumps. These man-made territories, with their own seismic and sociological realities, reflect a global addiction to manufactured plastic, metal, rubber, cardboard, and paper products. The mountain ranges of garbage declare to the heavens our criminal obsession with the discardable. Many of the objects making up these trash terrains are designed to be used for less time than the life of a banana, but they endure as waste for eons. Chris Jordan’s images of decomposed sea birds with a belly full of bright plastic bottle caps reminds us that this garbage is the gift that keeps on killing.

Photo courtesy Chris Jordan www.chrisjordan.com

Perhaps the most obvious, most devastating revelation of their work is that the driving core of society today, everywhere, appears to be the carcinogenic belief that life is all about “me.” Immediate gratification takes absolute priority over the impact that may have on the next generation and why long-term environmental degradation is seen as a reasonable corollary to quarterly market gains. The 20th century’s thoroughly irresponsible adoption of the “disposable” as key to many blockbuster business models can be seen in the accumulation of plastic debris packed into massive, slowly swirling gyres in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Continents of discarded plastic crap are our collective, enduring marks on the planet, revealing the intimate and true story of our values and views.

The 1967 film The Graduate nailed the (then next) generation’s anxiety about the future and summed up the grown-ups’ myopic failure to recognize the dangers in the famous advice dispensed by the smug, established adult world: “Plastics. There’s a great future in plastics.” And perhaps Mr. McGuire was right, but not in the way he meant. Plastics are defining our future as they quite literally choke the life out of the oceans. GYRE: The Plastic Ocean, an exhibition at the Anchorage Museum in Alaska on view through Sept. 6, 2014, commissioned 25 artists to investigate, explore, and consider the plastic gyres we have deposited in our oceans. Again, it is artists and their highly disciplined ability to assemble immensely complex problems into comprehendible moments that gives us glimpses of a way ahead. An artist’s view can grapple the impossibly complex and provide us with nudge toward a way forward: together.

Courtesy of Susan Middleton/Anchorage Museum

Huge as the impact of industrial-scaled irresponsibility has been on the planet and therefore the next many generations is, it is a mild change compared with the paradigmatic shift ushered in by digital technology. While plastic chokes the oceans and air-born pollution is changing the global climate, digital technology is transforming what is possible—the future is reappraised just about every 18 months as Moore’s law rolls forward. How we harness the expanding capacity to process, crunch, digest, and sort data, and how we apply those new powers to solving problems and creating alternative possibilities, will define what is left spinning here in 100 years.

It is encouraging to see projects such as the Green Electronics Challenge emerge. This joint project between the U.S. and China—which is co-sponsored by Future Tense, the partnership of Slate, the New America Foundation, and Arizona State University, where I work—looks to pack together the critical and innovative thinking of trained artists, the technological precision and predictive capacities of science, and the crowdsourced, wiki-solution base of the DIY movement to address, specifically, waste produced by e-technology—the very technology that just might find paths through the current mess.

Courtesy Anne Percoco/Anchorage Museum

Projects such as the Green Electronics Challenge and the Zero1 Innovation Challenge understand full well that the waste pile is not something that will recede in the rear view mirror—the dustbin is history, present, and future. We need to own that—to stop squabbling and start working together, harnessing the critical encompassing thinking of artists and begin to focus on the future.

Future Tense is a partner in the Green Electronics Challenge, a competition for makers from the U.S., China, and elsewhere to create something new from electronic waste. For more information and to enter, visit the Green Electronics Challenge website.