Welcome to the Thirsty West

A monthlong series about the devastating drought facing a corner of the country.

Photo courtesy Eric Holthaus

Driving through the Arizona desert between Tucson and Phoenix, it’s easy to see the remnants of agricultural boom times. Irrigated agriculture in the Arizona desert peaked in the 1950s and has steadily declined as urbanization’s water demand has exploded. The road is flanked with abandoned cotton fields that have since turned into dust-storm factories. It’s not uncommon for the road to close and for day to turn into the night during the worst storms, which happen during the early summer months as the monsoon thunderstorms move north from the Sea of Cortez.

In some ways, it feels post-apocalyptic: Evidence suggests that human activity has moved somewhere else.

Improving technology has offset some of the more ridiculous uses of desert water. In the early days, farmers literally flooded fields of orange trees with water diverted from newly constructed dams. Wells have pumped at least two rivers dry in southern Arizona, where groundwater levels have dropped by hundreds of feet over the last century.

It took decades, but Arizona finally learned that it had to adapt to survive. Still, many obvious questions have no easy answer: How to balance economic growth and environment? Does fairness mean cities get first dibs over farmers, even though they were here first? Is climate change a game changer? The issue of water in the Southwest is a preview of 21st-century politics worldwide.

Everywhere there are signs of adaptation to this new reality, or at least attempts at it. A billboard just north of Tucson pitches FiberMax, a variety of genetically modified cotton seed originally developed by Bayer in Australia. It promises to increase production in semiarid climates like this one and has become one of the top-selling cotton brands in the nation.

The shift away from irrigated agriculture in Arizona hasn’t come without a fight. By some measures, farmers are still winning. According to the Arizona Department of Water Resources, more than two-thirds of Arizona’s water is still used to irrigate fields, down from a peak of 90 percent last century.

Decades ago, state officials in Arizona begin to plan for a future without water—and that meant sacrificing agriculture for future urban growth. A massive civil engineering project in the 1960s diverted part of the Colorado River to feed Phoenix and Tucson. Those cities could not exist in their current state without this unnatural influx of Rocky Mountain snowmelt. Now there’s tension across the region, as the realities of climate change and extreme weather catch up with the business-as-usual agricultural bedrock that laid the foundation for the economy here.

In some ways, what’s happened in Arizona could be a preview of California’s future.

This year in California, fields are being fallowed as the state battles a drought as intense as anything it has faced in centuries. Federal water allocation for many farms has been cut to zero for the first time. California’s vast energy-intensive infrastructure for moving water around the state has been choked off by lack of snowpack and low reservoir levels. In some places, there’s simply nothing left to do but wait for rain.

By all accounts, March is the make or break month for the California drought. That’s because snowpack peaks on or about April 1. A big storm last week boosted levels to their highest point so far this winter, but that’s not saying much. Snowpack is still 70 percent below normal, near record lows. California’s Sierra range is nearly devoid of snow, supplemental water from the Colorado River has been reduced for the first time, and groundwater levels are “falling at an alarming rate.” Whatever is up in the Sierras at the end of this month will form the basis for the reserve water that will get California through the summer—and what promises to be an epic fire season.

The present-day Southwest was born from a pendulum swing in climatic fortunes that has no equal in U.S. history. Research at the University of California, Berkeley shows that the 20th century was an abnormally wet era in the West and that a new mega-drought may be starting. With the added pressure of climate change, there’s simply no way to count on continued supplies of water at current usage rates.

Looking ahead, the U.S. Global Change Research Program projects 20 percent to 50 percent less water by the end of this century, with temperatures 5 to 10 degrees warmer (Fahrenheit). The newly released National Climate Assessment confirms the trend: The theme of the 21st century in the Southwest will be more people with less water.

Photo courtesy Eric Holthaus

Don’t get me wrong: This has always been an extreme environment. But over the thousands of years of human civilization in this corner of the world, people have adapted to little water. Problem is: The water supply/demand calculus has never changed this quickly before. About 100 years ago, the balance started to tip. Groundwater was invested for agricultural purposes. Massive civil engineering projects pulled more water from rivers. The human presence in the desert blossomed.

Now, the West is thirsty and getting thirstier.

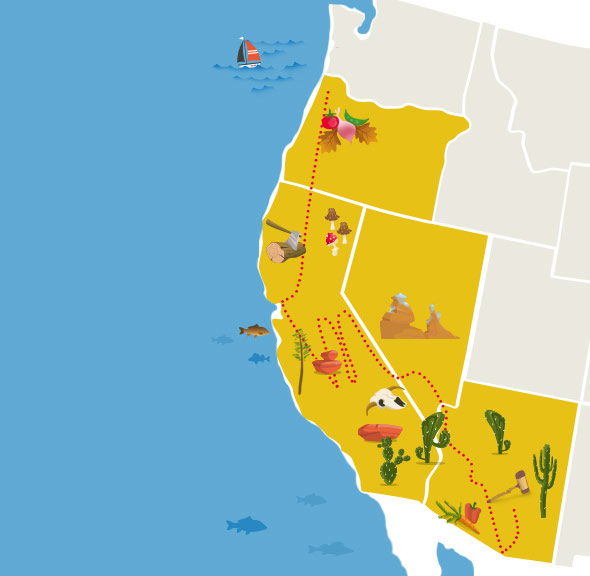

All this month, I’ll be sending dispatches from the desert, discussing the water crisis that has been with the modern Southwest for decades, but seems to be coming to a head this year. I’ll be visiting produce warehouses on the Mexican border, talking to farmers in California’s drought-stricken Central Valley, examining which technologies could buy cities time if the taps are cut off, and asking questions about what people and governments are doing to prepare for a future with less water, with lots of stops along the way. It’s my attempt to trace the impacts of the current drought from plow to plate and beyond.

This week, on a hike through the saguaro cactus forest near Tucson, my wife and I were caught in the first rainstorm in two and a half months. For a brief few hours, the desert came alive: Birds were singing, and the mesquite trees became noticeably greener. But as quickly as it came, the rain was gone. Hours later, only a few puddles remained alongside city streets. The next day, the sun was back, baking the desert once again.

Next: In the second part of the Thirsty West, Eric talks to Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild about how the city can survive climate change.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Tucson, Ariz.

Tucson, Ariz.

Nogales, Ariz.

Las Vegas, Nev.

Death Valley

Sequoia National Forest

Hanford, Calif.

Denair, Calif.

Tulare, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Oakland, Calif.

Sheridan, Ore.