A version of this article originally appeared in New America’s Weekly Wonk.

In a world where there is vast disagreement about almost anything complicated, there is widespread consensus across virtually every partisan and ideological division that the United States faces an unfair and destructive “digital divide” that is keeping our nation from taking full advantage of the transformative potential of the Internet. About 30 percent of Americans still don’t have broadband at home—an unacceptable situation in a world where schoolwork, job applications, government services, and even family communications have all moved online.

That is one of the reasons Comcast, where I am an executive vice president, developed the nation’s largest and most comprehensive broadband program for low-income Americans before our acquisition of NBC Universal and voluntarily proposed it to the FCC as part of the review of that acquisition. In a little more than two years, we and thousands of community-based and governmental partners have successfully connected more than 250,000 families—more than 1 million Americans—to the Internet through this Internet Essentials program, which offers broadband service for less than $10, heavily subsidized computer equipment, and digital skills training (in print, online, and in person) to families with children eligible for the national school lunch program.

A few weeks ago, Comcast announced a new partnership with a revolutionary online learning nonprofit, the Khan Academy. By providing unprecedented promotion and support, this effort will expose millions of kids to the acclaimed video lessons available for free at Khan and hopefully help connect more families to the Internet at home.

Internet Essentials and the Khan partnership aren’t complete solutions to the problem of the digital divide—and we haven’t accomplished these amazing results by ourselves. But any rational observer would have to acknowledge that we have made a difference—a big one. These are real and concrete steps forward toward equalizing opportunity in this country—what President Obama calls “the defining challenge of our time.” And we’re not done yet.

But New America Foundation policy analyst Danielle Kehl’s recent Weekly Wonk column, which also ran on Slate, joins a minority of critics in questioning Comcast’s motives and cynically suggesting that Internet Essentials is little more than a bait-and-switch tactic to drum up new customers. (Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University.) Peering into what the piece concedes is a “hypothetical” future, it further speculates that the partnership could lead Comcast to “pick winners and losers” in digital education by favoring Khan’s Internet traffic online. These claims are just wrong.

The results of Internet Essentials speak for themselves. It’s helped 1 million low-income Americans connected to the Internet. Ninety-eight percent of them say their kids now use the Internet for homework. Fifty-nine percent say it has helped someone in their household find a job. And anyone who questions the immediate, real-term value of this service should talk to the families who have seen it transform their lives, as I have.

The piece dismisses the effort as little more than a corporate showpiece, compelled by regulation, but that’s simply not the case. It was Comcast that proposed this idea to the FCC, which has since endorsed the model and tried to expand it to other broadband providers. With input from thousands of partners, including major service organizations like Big Brothers/Big Sisters, Easter Seals, the NAACP, and NCLR, we’ve increased speed, expanded eligibility, and made dozens of other enhancements. And our marketing and outreach effort and investments like the Khan Academy partnership go far beyond any requirement or regulation—we do these things because we sincerely believe getting more families connected is the right thing to do.

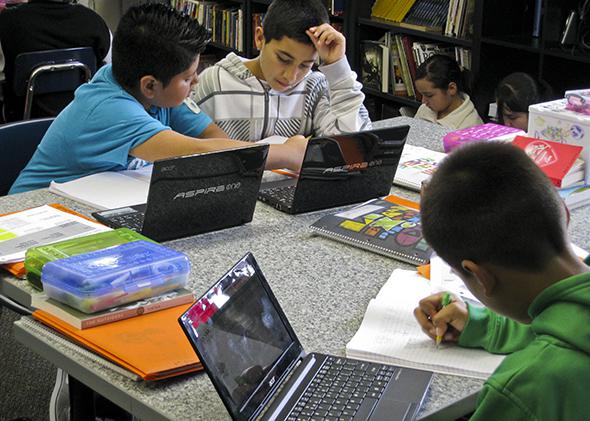

The Khan partnership in particular is designed to address one of the most frustrating aspects of the digital-divide conundrum. Study after study shows one of the greatest obstacles to bringing holdout homes online is convincing them the Internet is relevant to their daily lives—that there is value for them online. In a world where affluent children have private tutors, college admission “coaches,” and vast enrichment opportunities and experiences, we believe that access to Khan’s lessons are a powerful way to expand opportunities for lower-income families. In fact, it may be the single best driver of value and relevance of the Internet for low-income parents of school-age children.

The original article contends that Internet Essentials service is too slow to be useful. But Internet Essentials customers now download at 5 mbps, well above the 3 mbps the FCC uses for its map of broadband availability and fast enough for high-end applications like the full-motion video needed for lessons at Khan. The piece is also wrong to assert that this is slower than service offered to non-Internet Essentials customers; entry-level service in most of our markets includes a 3 mbps service option.

As to the issue of families losing access when kids graduate, the piece ignores our commitment to continue to offer Internet Essentials to any family so long as there is a single eligible child in the household. And while neither Internet Essentials nor the Khan Academy is a complete solution to the digital divide or the problem of unequal opportunity more broadly, that’s no reason to scoff at the important work being done to help hundreds of thousands of families right now.

Finally, the piece denigrates the program by speculating Comcast might “pick the winners and losers in the online educational market” by favoring Khan’s Internet traffic and degrading service to others. This is beyond what anyone could characterize as even reasonable speculation. There is no evidence whatsoever to support this outlandish assertion, and Comcast has made it crystal clear that it will not degrade or slow down Internet traffic for any of our customers or any website (Khan competitors included). And if that’s not good enough, the Comcast/NBCUniversal transaction order, to which we agreed, bars that kind of behavior.

And that points us to the biggest problem of all—the unrelenting, corrosive cynicism that runs throughout the entire piece. Fact-based criticism is one thing. But assuming the worst in all cases (“hypothetically,” of course) and writing off any possibility that others might have decent or honorable motives is another. As Stephen Colbert put it, “cynicism masquerades as wisdom, but it’s the farthest thing from it.” And the consequences in this case are destructive and real: what do we say to children whose families chose not to sign up for affordable broadband because someone wrongly convinced them the whole thing was a scam?

Closing the digital divide means rolling up our sleeves and working together—all of us in the private sector, the nonprofit and public policy community, government, and as individuals. And Comcast stands ready to work with everyone who shares that goal.

Danielle Kehl responds:

The digital divide is an incredibly complex and important issue with far-reaching implications for our country’s future—on this point, Mr. Cohen and I are in complete agreement. Our perspectives diverge, however, when we drill down into the specifics of what a solution to this problem looks like and how we get there. The goal in taking a skeptical look at the recent announcement about the Comcast–Khan Academy partnership was neither to score cheap points against Comcast nor to discourage, as Mr. Cohen suggests that I am trying to do, families with school-age children from signing up for Internet Essentials because it is a “scam.” Rather, what my colleagues at the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute and I want to do, along with analysts at organizations like the Roosevelt Institute, is push the conversation much further. We need to start talking seriously about why the Internet is so expensive in the United States, what meaningful broadband adoption really looks like, and how to help the millions of low-income Americans who don’t have school-age children afford high-speed Internet connections. The nature and tone of Mr. Cohen’s response are defensive, but it fails to explore the ways in which Comcast might move beyond Internet Essentials to address the underlying, fundamental problems that exacerbate the digital divide in our country. After all, if we are serious about solving this problem in the United States, we need to be willing to admit when a solution looks good but isn’t really sustainable or when it doesn’t address the systemic problems that exist. And it’s true that Comcast proposed Internet Essentials as part of the NBC merger—but the response fails to mention that, according to the Washington Post, in 2009 the cable company delayed implementing a program aimed at low-income families so that it could be used as a bargaining chip in the upcoming merger negotiations. We would love for Comcast to prove us wrong and start offering truly high-speed, low-cost Internet service to Americans across the country. But in order to get there, we have to be willing to evaluate the current situation with a critical eye.

David L. Cohen replies:

This productive exchange shows areas of agreement and disagreement. We have never argued that Internet Essentials alone will close the digital divide. But it is indisputable that IE is a major and successful effort—it’s been called the “largest experiment ever” in this space by an official of the NAACP. Focusing on the fact that more remains to be done doesn’t do justice to the good work that is underway. On the question of affordability, the ITU says the U.S. has the OECD’s most affordable entry-level fixed broadband pricing. In any event, I appreciate New America and Slate hosting this important dialogue—we should all be talking, and listening, to one another more on real ways of closing the digital divide.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.