This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate that explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. On Dec. 9, 2013, Future Tense will host an event on patent reform in Washington, D.C. For more information and to RSVP, visit the New America website.

The “smartphone war” has roared back into the headlines. In late November, a jury raised the total amount of damages that Samsung owes Apple to more than $900 million for infringing Apple’s patents on the iPhone. And a month earlier, the Rockstar consortium filed a patent infringement lawsuit against Google and some manufacturers of Android smartphones. As one commentator remarked, Rockstar’s lawsuit, which is the first direct attack on the entire Android ecosystem, represents the “thermonuclear war” that Steve Jobs promised to bring to Google.

These recent legal skirmishes in the smartphone war have added fuel to the fire raging in the public policy debates about the patent system. Many claim that there has been an unprecedented “patent litigation explosion” and that the “patent system is broken.”

But as I explained in recent testimony before the Senate, these allegations are mostly the byproduct of inflammatory rhetoric and unscientific and unreliable studies. In fact, the smartphone war is anything but unprecedented. Our patent system has long, and effectively, promoted innovation—and legal battles, sometimes substantial legal “wars,” have always occurred along the way.

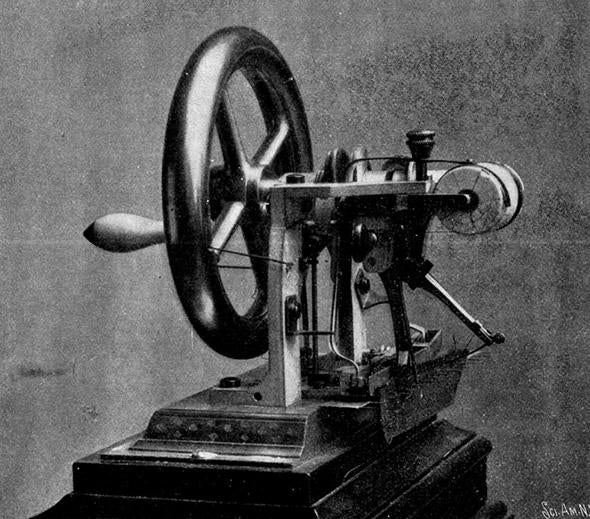

The first of many such patent wars was more than 150 years ago: the sewing machine war of the 1850s. Not only was it the very first patent war—it had all of the trappings of the following patent wars up through today’s smartphone war. Although some may think the sewing machine is a mundane household product, it was a technological achievement on par with today’s smartphone or tablet. The sewing machine was the result of numerous innovative contributions by different inventors, all of whom received patents on their particular inventions. The result: Each sewing machine produced, sold, and used by consumers infringed multiple patents, which spurred massive litigation by the patent-owners against manufacturers, retailers, and consumers alike.

In addition to the numerous overlapping patents covering each sewing machine, the sewing machine war also entailed the active selling and purchasing of patents, high-profile lawsuits, expensive litigation, lawsuits in multiple venues, complaints about overly broad or vague patents, and much more. Yet many commentators allege these elements of today’s smartphone war are new, dangerous threats to innovation. All things old are indeed new again, which in this case is more truth than cliché.

Even the prominent role of “nonpracticing entities” (also known by the pejorative epithet “patent trolls”) in patent litigation is not new. The sewing machine war was started by Elias Howe Jr., who didn’t make sewing machines. At the time, Howe’s business model was solely licensing his patent on the lockstitch to sewing machine manufacturers; one historian referred to Howe’s “main occupation” in the early 1850s as “suing the infringers of his patent for royalties.” In short, if Howe were alive today, people would call him a “patent troll,” although it’s more accurate to say that his business model was patent licensing. In fact, Howe’s licensing and litigation practices were only possible because he had the financial backing of a business investor; again, as historical research has shown, this is something that has been embraced by patent licensing companies from the 19th century to today.

The numerous lawsuits comprising the sewing machine war occurred in many different states, in different court houses, and among many different individuals and companies as well. While not the global legal conflict that the smartphone war is today, we must remember that this was a time before telephones, typewriters, and other modern marvels of communication, and travel was still predominantly by horseback, canal, or coal-powered trains. Widespread education was also minimal; many of the inventors who contributed to the sewing machine had no formal training in mechanics or even “natural philosophy” (science), and juries and judges were just as uneducated about such matters. As a result, patent infringement lawsuits were just as complex, lengthy, and difficult proceedings to undertake as they are today. Judges and commentators complained incessantly about the delays of justice and the costs of bringing or defending against a lawsuit. A single deposition transcript in just one of the many lawsuits in the sewing machine war was more than 3,500 pages in length—the only person who benefited from this was the lawyer who billed for his time.

There are many more similarities between the sewing machine war and the smartphone war than can be described in a short essay (you can read more in my 2011 law review article on the subject), but it’s important to recognize that the sewing machine war was not an anomaly. It ended in 1856 when the patent-owners created the very first patent pool—a new and innovative patent licensing company at that time. Patent pools are still used to this day for technological inventions covered by many overlapping patents, such as digital video (MPEG), wireless ID technology (RFID), and, of course, the telecommunications technology owned by the Rockstar consortium (a licensing company backed by Microsoft, Sony, Nokia, Blackberry, Apple, and Ericsson). Patent wars, and their resolution via patent pools or other commercial arrangements, have been commonplace with each technological leap forward. There were patent wars over the incandescent light bulb, electrical distribution systems, telephone, automobile, airplane, radio, laser, medical stents, and others—even disposable diapers in the 1980s.

By these historical standards, the smartphone war isn’t even much of a patent war, at least not yet. The total number of patent lawsuits over smartphone technology amount to several hundred lawsuits, at most. In 2011, an estimated 100 patent lawsuits were filed in the smartphone industry. But the telephone war at the end of the 19th century comprised 587 patent lawsuits filed just by Alexander Graham Bell’s company over the span of a couple of decades. Over the same period, more than 600 lawsuits were filed in the patent war over the incandescent light bulb, involving Thomas Edison and many others. One historian has found thousands of patent lawsuits filed annually against consumers, retailers, and manufacturers throughout the 19th century.

These statistics reveal that, contrary to many claims about the smartphone war and patent litigation generally, there is no “patent litigation explosion” occurring today. The patent litigation rate between 2000 and 2010 was a constant 1.5 percent. As reported by award-winning economist Zorina Khan, the average patent litigation rate between 1790 and 1860 was 1.65 percent. In fact, for three decades in Khan’s study patent litigation rates were higher than today’s litigation rate. Between 1840 and 1849, patent litigation rates were 3.6 percent—more than twice the patent litigation rate of the past decade. Also, it bears noting that the measurable increase in patent litigation in 2012 was entirely the result of legal changes to the patent system instituted by the America Invents Act of 2011, as recognized by Congress’ GAO Report on Patent Litigation (August 2013).

Of course, simply because something has happened repeatedly before does not mean that it is necessarily correct. But claims today that the “patent system is broken” are based on a mythical historical standard—and they are motivating Congress, regulatory agencies, and courts to make substantial revisions to the patent system. These “reforms” impose substantial legal burdens on licensing and selling patented innovation in the marketplace and on suing infringers. It’s striking that, while there are certainly some bad actors in the patent system today, there are no studies whatsoever on the effect these legal revisions will have on legitimate patent owners.

History thus reminds us that incredible innovation has occurred throughout all of the patent wars, just as everyone is benefiting from a vibrant high-tech and telecommunications industry today.