A magician, it is said, never reveals his (or, in very rare cases, her) secrets.

Unless he’s involved with open-source magic—in which case he will happily risk running afoul of the Alliance of Magicians.

Open-source magic is not about slapping magical secrets up on YouTube; there are more than enough eager teenagers and fun-ruiners willing to do that. Instead, it takes a lesson from the open-source technology activists who believe that better innovation comes through collaboration. The idea here is that magicians should be working with technologists, artists, programmers, scientists—everyone—both to create new illusions and to bring magical thinking to other disciplines. Furthermore, the technology behind those illusions should be, at least in part, freely available.

Intellectual property is a bit of a thorny issue in magic. Magicians’ illusions can be copyright-protected, but many—including Teller of Penn & Teller fame, who is suing a Dutch magician for stealing and trying to sell his “Shadows” illusion—have seen their effects ripped off, and litigating those cases is difficult. So magicians are a little touchy about anything that implies opening up the secrets of illusions, their livelihoods, to potential theft. However, say open-sorcerers, magic’s traditional emphasis on secrecy and jealously guarding IP means that too little collaboration happens at all and that when it does happen, it tends to be shrouded in nondisclosure agreements and secrecy. In order to revitalize magic, to keep it fresh, they say, it needs to open up.

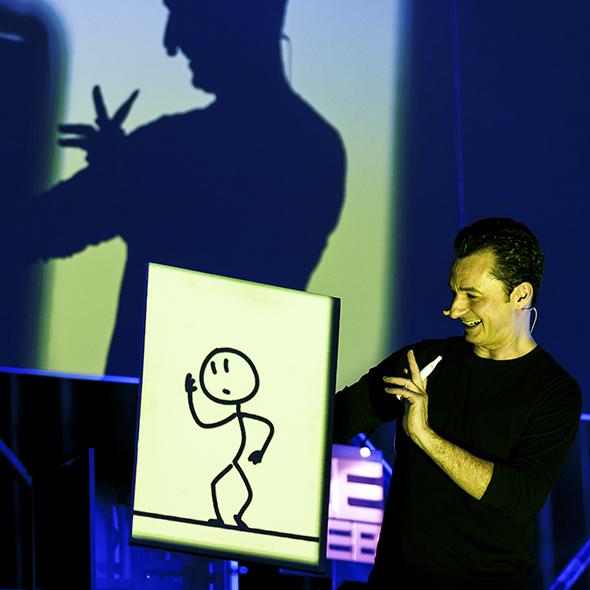

Two of the magicians talking the most about open-source magic are popular techno-illusionist Marco Tempest, who is a director’s fellow at MIT’s creative tech incubator, the Media Lab and has given TED talks, and Kieron Kirkland, “magician in residence” at Watershed, a digital creativity development studio in Bristol, England. Tempest, who is originally from Switzerland, is, in many ways, the father of the movement. He became interested in magic at about age 8 and joined the circus, a state-funded production that toured during the summers, at 12; at 22, he won the New York World Cup of Magic. His interest in technology is relatively recent, only about six or seven years old, but he describes it as his passion. In his magic shows, he uses augmented reality and interactive projections, and he’ll soon be employing a magic robot “assistant” called Baxter, which was developed with the Media Lab. When I spoke to Tempest in his “magic lab” in New York City via Skype, his lovely assistant, all long arms and blank screen face, was hulking in the corner behind him.

“Magic is a super-introverted field,” he said. “There is a lot of knowledge that has never been liberally shared with other fields of research. … What if, as part of our creative practice, we could share the stuff we come up with and make it available to other people, not only to magicians?”

In particular Tempest means technology and science. Magicians, he says, have long been skilled at understanding audiences on a psychological level and creating interactive experiences. At the same time, he adds, “You could say that the whole world of interactive computing is an engineered illusion.” So there’s a lot of overlap, or at least room for partnership—if Siri had been designed by a magician, Tempest says, she probably wouldn’t fail. “It wouldn’t be either she knows or doesn’t know; there would always be another question. … We would use cold-reading skills.”

Collaboration also means, he says, allowing those who’ve had a hand in creating new tech or a new illusion to share in its ownership. According to Tempest, big-name magicians typically contract illusion engineers, technologists, or other magicians to help them design new effects; those contracted are expected to sign secrecy agreements and have no ownership over what they may create. “What good comes from that?” he asks. The process makes it impossible for co-creators to refine and improve their work over time. By contrast, when Tempest and his collaborators create new technologies or effects, they share in the ownership, or he makes the work freely available to other developers. “Sometimes things take a life of their own and go completely somewhere else, and that’s very cool.”

They just have to convince the other magicians why that’s cool.

On Nov. 12 and 13, Kirkland and Watershed hosted what he billed as the world’s first “Magic Hack.” They invited about 25 magicians and technologists to sit down in a room and get to making. By the end of the weekend, they’d come up with a number of really cool new illusions and ideas, like a voodoo doll that, when pinched or pulled, caused the magician—blindfolded, of course—the same pain.

But Kirkland felt like it was a bit of a struggle to get other magicians involved: “The magicians didn’t get it at all. They were massively suspicious, [thinking] ‘They’re going to steal my ideas,’ ” recalled Kirkland. (In effort to make those who did join more comfortable, the hack began with an invocation of a kind of magic circle, a promise not to reveal the secrets of what they’d created with anyone outside the hack. Which is a little beside the point, but baby steps, baby steps.)

The thing is, some magicians don’t believe that Kirkland and Tempest are really onto anything new. “Magicians have always used the latest technology,” whether that’s in how they create illusions or how they present illusions to their audiences, said Will Houstoun. Houstoun is a magician who’s working on his Ph.D. in Victorian magic and is the editor of the Magic Circular, magazine of Britain’s venerable Magic Circle society. (Prince Charles is a member, having gained entry with his cup-and-ball trick in 1975.) Magicians have long collaborated with technologists and experts from other disciplines to achieve illusions, he said—they just don’t talk about it too much. Moreover, magicians have also always taken advantage of the latest tech to frame their magic, to set up the illusion. For example, 19th-century French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin used ether and its recently discovered medical applications to dress up his levitation illusion—he told audiences that if consumed in sufficiently concentrated doses, ether would literally make the user lighter than air; then he’d make his dosed-up assistant appear to float. That’s not terribly different, Houstoun says, from modern magicians pulling a live butterfly off a picture of a butterfly on an iPhone: it’s all using new technology to frame old tricks.

But more to the point, Houstoun continued, too much technology in magical illusions might not be a good thing. Technology itself is inherently magical—the fact that one can communicate with a person halfway across the world via a tiny, interactive box, is wondrous. But you don’t want the audience to simply explain away the illusion by saying, “Oh, well that’s just some clever technology.”

Plus, analog magic, to coin a phrase, still has the power to amaze. Houstoun said that he recently performed a card trick he’d found in a handwritten manuscript from the 1780s. “The world has completely changed, but a trick using a few pieces of paper that amazed people more than 200 years ago still amazes people today, despite all of the technology, all of the things that exist now,” he said.

Houstoun agrees that reverse collaboration—not using technology to make better magic, but using magic to make better technology—is valuable. But again, he says, magicians are already bringing magical thinking to the world outside their own discipline, and he’s one of them: Houstoun works with a U.K. nonprofit called Breathe Arts Health Research to teach magic illusions to children and teenagers dealing with hemiplegia, a partial paralysis of one side of the body, as part of their therapy.

So concerns about secrecy are probably not as much at the heart of resistance as the Alliance of Magicians might make it seem. Houstoun says that while the Magic Circle’s Latin motto, Indocilis Privata Loqui, roughly translates to “not apt to disclose secrets,” some secret-telling must happen in magic—otherwise, no one would ever become a magician. The rule of thumb around sharing magical secrets has to do with intent. If, for example, a magician writes an article for a newspaper or magazine, or, say, accidentally reveals the secret of the Aztec Tomb on TV, well, that’s not OK. But writing a book about magic to instruct other would-be illusionists is kosher, because anyone seeks out such a book already has an interest in magic that ought to be fostered. In that sense, Houstoun’s on the same page as open-source advocates Tempest and Kirkland, who see the movement as a means of sharing new technology or ideas with people whose interest should to be fostered.

In any case, magicians’ resistance seems to be more about not seeing the point of open-source magic. Which is itself a fair critique: Magic doesn’t appear to be in any real danger of decline, and simply adding a veneer of cool tech can seem a bit like just changing costumes.

Back in 1961, Arthur C. Clarke declared, accurately, that “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” So where does that leave magic?

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.