Most of us accept that our lives are limited. We’ll have a certain number of years—more than 75, we hope, but probably fewer than 100—and then we’ll die. The world will go on without us. An awareness of our own mortality, we tell ourselves, is part of what makes is human.

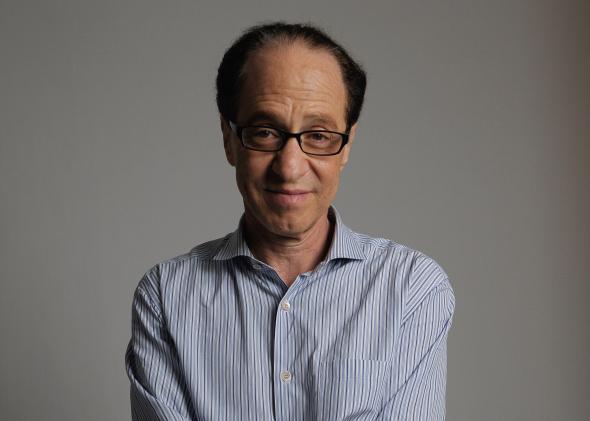

Not Ray Kurzweil. A renowned computer scientist and inventor, Kurzweil, 65, decided decades ago that mortality wasn’t for him. He didn’t have to die, and he wasn’t going to, if he could help it. Fortunately, he believes he can help it—and he’s been working feverishly at the task of staying alive ever since.

“How long do you think you will live?” I asked Kurzweil in a recent phone interview.

He rarely misses a beat in conversation, but he was quiet for just a moment before replying. “I think I have a good chance—I would put it at 80 percent—of getting to the point where it becomes indefinite, because you’ll be adding more time than is going by to your remaining life expectancy.”

In olden days, a man who insisted he could live forever would have been viewed as a strong candidate for either crucifixion or veneration. These days he’s a natural candidate for a top job at Google, where “solving death” is just another a pet project of CEO and co-founder Larry Page. Kurzweil is a part-time adviser to the company’s new Calico venture, which is focused on finding a cure for aging. But his day job is as an engineering director, working alongside a younger generation of artificial-intelligence wizards on, among other things, a project called “Google Brain.” His goals at Google, which include teaching machines to understand language, dovetail in somewhat complex ways with his overarching goal of cheating death.

Where Spanish adventurers believed in the Fountain of Youth, Kurzweil believes in what the mathematician John von Neumann called the “singularity”—a point in human progress at which our machines become as smart as we are. They won’t rise against us, though, because they will by that point be very much a part of us. Already our smartphones are becoming extensions of our minds. Kurzweil forecasts that we’ll eventually be implanting computers and nanobots in our bodies and brains to enhance their natural functions. (That’s bridge two on the road to immortality, in Kurzweil’s scheme.) And someday—by 2045, to be precise—we’ll have machines so sophisticated that we’ll essentially be able to back up our minds to the cloud. (That’s bridge three.)

Kurzweil has spread his ideas widely and defended them energetically against critics, of whom there are many. He has made many predictions, a surprising number of which have come true, like his late-1980s forecast that a computer would win the world chess championship by 2000. He seems unperturbed by the ones that haven’t, like his 1999 bet that within 10 years a majority of text would be created using continuous speech recognition. (Kurzweil insists that he was not far off, citing Siri as an example.) He’s a variety of believer—not in any god, but in the potential of humans to achieve godlike powers with the aid of the technologies we build.

The key to his theory is that these technological advances won’t transpire steadily over time, but rather exponentially, so that each year brings more change than the last. In fact, this is what’s been happening for decades in the realm of computer processors, where it’s known as Moore’s law. It’s how we’ve gone from computers the size of houses to computers that fit onto the frame of a pair of glasses. Kurzweil believes similar laws of accelerating growth govern all forms of information technology. And he believes that all technology will eventually become a form of information technology. Ergo, technological progress is about to get really, really fast.

So why hasn’t average life expectancy—or even the age of the oldest human alive—budged much over the last few decades? Kurzweil says we’re just approaching what he calls “the knee of the curve.” That’s the point at which an exponential function starts to rocket upward. Longevity, Kurzweil explains, “is going to transform from having been a hit-or-miss affair where progress was linear … to where it is now an information technology and therefore subject to my law of accelerating returns.”

Even if the singularity is near, there’s no guarantee that Kurzweil himself will live to see it, given that he’s already 65. That’s why he’s been rigorously maintaining his health in anticipation of the techno-rapture. (He even once wrote a book on dieting and healthy living.) “I expect to be in good shape when we get to that point,” he told me. “We’ll get to the point where we dramatically extend human life expectancy because we will have wiped out major diseases, and ultimately all disease as well as the aging process.”

For Kurzweil, then, life is a sort of race against the clock. If he and his fellow scientists and software engineers make the right moves, he could live to see the 22nd century, and then the 23rd. If not, he will have blown his one shot at immortality.

It sounds like a lot of pressure.

Isn’t it stressful, I asked him, to live with the conviction that you have the power to avert death if you can just find the right answers? Or is it somehow energizing?

“Both,” he said. “But it would be more stressful to contemplate the inevitability of the tragedy death with no credible plan to avert it.”

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.