When envisioning a gleaming, medically enhanced future in which things like implant technology, super-personalized medicine, and organ regeneration enable humans to radically extend their lifespans, futurists sometimes forget that the human family also tends to change with time. In a world where people rise each day to spit into a bucket and send their bio-readings to a Google Medicine cloud that records and monitors their daily measurements, it would be a mistake to think the identity of the person spitting in the bucket beside yours will never, ever, ever alter.

In fact, you might call this the “Jetson fallacy,” in honor of the classic early-’60s cartoon whose writers envisioned a human space colony 100 years into the future (that is, the 2060s). Living as they did in a city endowed with flying-saucer cars, robot housekeepers, and elevated dwellings, the Jetsons nevertheless remained strangely Cleaver-like in roles and composition: a nuclear unit comprising two kids, a dog, a breadwinning husband—George—who went to work at Spacely Space Sprockets, and a homemaking wife, Jane, who sweetly snatched his wallet before zooming to the shopping mall. Creative as they were in imagining the landscape of the future, the writers were oblivious to the tectonic changes—divorce, the sexual revolution, feminism, the entry of women into the workforce—poised to explode the American family.

With that cautionary tale in mind, I’d propose some additions to the compelling “longevity scenarios” that Joel Garreau discussed in Future Tense as a way of sketching out possible outcomes for what human life might be like in an age of 100-plus lifespans. In the four scenarios that Garreau persuasively offers, it is 2030 and a hypothetical couple, John and Ann Grant, parents of two adult children, are entering their 80s. Depending on the rate at which medical science has moved forward—and the ability of public policy to make these technologies available—the Grants A) are not in much better shape than generations before them; B) can expect to live several more decades, but doddering and frail; C) feel healthier and fit than ever, with 60 or 70 more great years ahead of them; or D) find themselves in a wonderfully altered world where their children can plausibly expect something like immortality. In all four scenarios, John and Ann, bless them, remain married.

But we might also consider scenario E, in which John and Ann Grant take a hard look at each other after Sarah and Emily leave home for college and decide that while they’ve had a great run, life is long—very, very, very long—and they’d like to explore other options. They divorce; John marries a woman 20 years younger, ensuring he will have a partner who can look after his well-being, taking him to all his body-part-replacement appointments as he moves toward his first centennial. Ann finds herself living among exponentially more single women, her social life confined to playing online poker with other divorcees and widows, because humanity persists in thinking women should only partner with men their age or older, even as those men have taken younger second or third or fourth wives. In scenario F, our thinking changes and we decide that women, like men, should be able to dip down and date younger partners, so Ann, at 120, takes a well-sculpted 70-year-old boyfriend, but prudently decides to live with rather than marry him.

Whatever pair-bonding opportunities we as a culture allow Ann, we of course will not think it strange if John and his new wife have a child or two to seal their new alliance, meaning Emily and Sarah accrue half siblings who are significantly younger than they are.

As for Emily and Sarah: Likely as not they are the breadwinners in their households, given that even now, 40 percent of mothers are the primary earners in their households, a trend that shows no signs of abating. In scenario G, Sarah and Emily by 2030 are the ones who go off to Spacely Space Sprockets every morning and leave a male partner—husband, boyfriend, cohabitant—in charge of the dog and the kids. Or maybe there is no male partner: Let’s say Sarah gets tired of waiting for the right guy, so she freezes her eggs, works hard at her tech startup, and conceives at age 50 with the help of a commercial sperm donor. Emily is in a same-sex marriage and with her wife adopts a child. So now we have a Grant family comprised of exes, steps, half siblings, spouses, cohabitants, birth parents, and people whom the reproductive industry sometimes calls “collaborative reproducers.” Thanksgiving gatherings are fun, but require a massive number of genetically engineered turkeys.

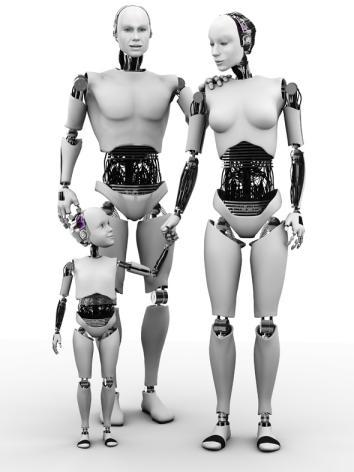

In fact, by the time people are living to 150, the human family has changed—not only the immediate family but the global human family. Typically, when we think of our own extended ancestry, we picture an inverted pyramid starting with a common ancestor, expanding outward with each generation. But by the time Ann and John Grant are 150, we may be living in a world where the family has itself become a kind of a cloud, a networked or latticed arrangement of relationships.

Why think about family composition when we’re talking about longevity? Because, in addition to being an inventive species, we are a caregiving species. Our relationships matter. The care we do—or do not—give one another is a big factor in how long we live. Married people tend to be healthier and to live longer. This will remain true in a world where organs can be grown in Petri dishes or spinal cords regenerated from stem cells. Somebody still has to take you to your third artificial heart replacement and drive you home from the hospital and comfort you if it hurts and make sure you get the right mix of pain meds and anti-inflammatories and that you do your physical therapy. Even if babies are someday conceived and gestated in a laboratory, somebody must care for infants to ensure they grow up to be loving, empathetic, mature human adults. There is an intriguing theory, the grandmother hypothesis, that attempts to explain why human females live past their reproductive years, a trait we share with very few species, among them killer whales. The hypothesis holds that the evolutionary purpose of grandmothers is to forage for grandchildren, and watch them when the parents are gathering and hunting. Cultures that utilized grandmothers to caregive, this theory goes, were the ones that enjoyed a spike upward in longevity.

And here’s the thing about caregiving: It doesn’t get more efficient with time. Unlike computer technology, human caregiving doesn’t double in processing power every two years. It remains slow and labor-intensive. Children require an enormous amount of care, and so will we, as we expand our lifespans to the next century. We will require physical care, but also emotional and psychological care. How we experience life as we approach 120 or 150 depends on the technology we create, and our access to that technology, but it also depends on our access to people we love and who love us back. What is the future of human pair bonding? Serial monogamy? Serial cohabitation? The death of marriage? A world of people who are 150 and living alone? Will assisted living, the private sector, replace the care of a spouse? Who are the close companions of tomorrow? Will a new kind of marriage evolve? Now that we have largely moved from an idea of marriage as procreative to marriage as companionate, will there be a new model: the caregiving marriage?

As our relationships evolve—halves, steps, exes—they may become more distant, less intimate. Who will assume responsibility for our physical and emotional well-being? We probably need a whole alphabet of scenarios for how the human family will evolve, but let’s not forget that the people we live with, and the way we live with them, will change as radically as our technology—and have an equally profound impact on our health and happiness, whatever outpost of space we eventually colonize.