We’ve been to the moon and just about everywhere on Earth. So what’s left to discover? In September, Future Tense is publishing a series of articles in response to the question, “Is exploration dead?” Read more about modern-day exploration of the sea, space, land, and more unexpected areas.

Courtesy of AMC

At age 14, I began reading my first Shakespeare play—Romeo and Juliet—for English class. It only took a line or two before my first profound, literary thought began to percolate: “This is English?!”

It was an important early lesson in the evolution of language—how cultural understandings shift between eras, how time twists words and constructs new definitions.

Yet, it was an incomplete one. Back when I was in school, readers could see an antiquated expression sprinkled throughout early texts—but it was impossible to scientifically trace its rise and fall without studying thousands of volumes. Even the Oxford English Dictionary, with its rich recorded histories of just about every English word, couldn’t tell us how many times journalist appeared in 1888 vs. 1978. Few attempted that task. Fewer survived.

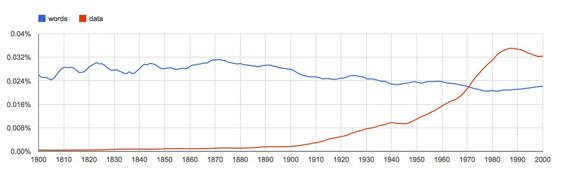

But when Google’s Ngram Viewer launched in 2010, it transformed that Everest-level word exploration into a seconds-long bunny hill search—and illecebrous, captivating graphs. Using data from Google Books (the company has digitized about 20 million books and uses data from about 6 million in the viewer), the Ngram Viewer plots frequency of particular words and phrases across time.

Through this digital tool, we can explore the rise and fall of your great-great-grandmother’s vocabulary—the dustiest, rustiest words in the OED. During the viewer’s first day, language zealots performed more than 3 million word searches (parsing Google Books data) to see how use frequency ebbed and flowed across time. According to Google, the tool is now used about 50 times per minute. Those poetic word frequency graphs have sprouted everywhere.

Chart generated by Google Ngram Viewer

But now that it’s been three years since the hype and fanfare, some spermologers want to know: Has this new tool led to any legitimate discoveries—knowledge that has upended our sense of events or eras? In other words, what have we unearthed after three years of exploring an untapped trove of recorded history?

The Viewer has enabled many granular discoveries—think fossilized Mesopotamian cooking tool rather than Dead Sea Scrolls. “There are hundreds of little mysteries that one can resolve with the Ngram Viewer,” says Erez Lieberman Aiden, a founding father of the Viewer and the field of Culturomics (which studies human culture and history through the lens of massive datasets) and fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows. Take the mystery of donuts vs. doughnuts. When did the spelling change? Before the Ngram Viewer, “it would’ve taken a very long time to determine when that spelling transition took place,” Aiden explains. But according to the Viewer, the donut spelling starts to take off in early 1950s, right around the time Dunkin’ Donuts opened its first store. Of course, it doesn’t prove that Dunkin’ Donuts alone changed the spelling—but it does add a compelling dimension to the story.

The Viewer exposes Nazi censorship of philosophers in German texts and Chinese suppression of the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989. Its easily accessible, swith data could help writers of historic fiction TV shows, like Mad Men and Downton Abbey, produce more accurate and convincing dialogue. And it dismantles the narrative that the Civil War caused Americans to refer to the United States as a singular entity (the United States is) rather than a plural (the United States are). That long-held belief “is a phenomenal story line, kind of an inspiring story line,” Aiden says. “It brings together grammar and battle and has figured prominently in the works of prominent historians.” But as the Viewer has demonstrated, the reality is more complex. Americans were using both versions before the Civil War, but the singular overtook the plural starting in the early 1880s.

The Viewer also helps corroborate larger, semantic debates—like, do words actually evolve in the Darwinian sense?

And that was the question that set Aiden and Jean-Baptiste Michel, another Viewer founding father and co-founder of the Culturomics field, on the path to create such a tool in the first place. Back in 2007, Aiden, Michel, and a crew of undergraduate students decided to test the word evolution hypothesis by tracking irregular verbs over the past 1,000 years. They found 177 that were traceable (for instance, go and went, run and ran), plotted them manually, and discovered that the verbs did undergo a kind of evolutionary process. “The less frequent the verb, the more rapidly it becomes irregular,” Aiden explains. “Our work became this demo of how evolution by natural selection might work in a cultural study.”

It was work that Ted Underwood, an associate professor of English at the University of Illinois, had been eager to do since the ’90s. “But the tools weren’t available to chart word frequency on the scale that you need,” he said. He acknowledges that the tool hasn’t led to any discoveries that radically changed our sense of the past. Still, “it can confirm things, make us notice details we hadn’t previously noticed.”

If academics and researchers are actually using it, that is. Mark Davies, a professor of corpus linguistics at Brigham Young University, and the creator of a corpus of American historical English similar to Google’s work, says his colleagues aren’t using results from the Viewer in published research or presentations. Google Books data, he says, “is not even on the radar for most people. They look at these cute charts and say, all you can do is see a chart for one word—that’s pretty limiting.”

Even though Google recently tagged words by part of speech, there’s no way to check and make sure it labeled words correctly. “In academia, it doesn’t fly to say ‘Trust us, we did it right,’ ” Davies says. Another reason Davies thinks the Viewer hasn’t gained traction in his world: It doesn’t allow for searching by collocates, or words that occur nearby other words—but aren’t adjacent. (The Viewer does allow users to search for words that are next to each other.)

Linguists use collocates to understand how word meanings change over time. Gay, for example, used to be surrounded by color names and party—later, it began to appear by bisexual and marriage. (Technically, researchers can search collocates, but only if they download the underlying Ngram raw data set—and even then, Davies says, it’s a very complicated process). According to Google Research Manager Jon Orwant, the team is working on making it possible to search for words that are not just adjacent, but nearby.

Other academics fall on the opposite end of the Davies spectrum—they place too much power in the Viewer, and can misinterpret its results. A recent yemeles New York Times piece, for example, suggests that an uptick in toddler and similar words in postmodern fiction could signal “growing attention paid to children.”

“But in a dataset where novels are mixed with parenting manuals and cookbooks, it’s really hard to say what that increase tells us about the novel,” Underwood says. Researchers can break down their search by a fiction-related genre, but it’s not restricted to only traditional novels, as Aiden and Michel’s original research paper in Science explains.

Though it’s tempting to make dramatic claims using the data, it may be that the most valuable contribution of the Viewer so far isn’t a seismic cultural discovery. It’s the shift in the way we see—and question—our historic record.

“For me, it’s no question that the broader set of changes associated with [the Viewer and Google data] are changing the way research happens,” Underwood says, “We’re looking at an initial simplified outline of a picture that will get much richer and more interesting as we approach to take a closer look.”

The data will get richer, too, as we learn what to search for—and how to parse it. “People need more training in thinking in terms of questions that are good digital questions,” Davies says.

Aiden and Michel envision a more sophisticated Viewer in the future, one that uses more languages (the current one has data from nine, including both American and British English) and more puissant search functionality. Right now, you can search 22 corpora, or large groups of books, under genres like English fiction, Russian, and Hebrew. But there’s a potential barrier to significant progress: copyright laws. “Basically after the mid-’20s, you can’t really share the full text of most books published,” Aiden says. ”I think something has to happen in Congress in order to make these sorts of big data approaches to history move forward.”

There is, of course, one set of data you’ll always be free to search—your own. “If you could apply this technology to contemporary text on Twitter, blogs, or on your own corpus, you could search your own past and see trends in your own life,” Michel says. “That’s going to be possible.”

The Ngram Viewer, it seems, may be a little like reading your first Shakespeare play. It may take a while to adjust to a new syntax and rhythm—and at first, it can be jargogling. But once you do, the meaning behind that foreign diction begins to reveal itself.

More from Slate’s series on the future of exploration: Is the ocean the real final frontier, or is manned sea exploration dead? Why are the best meteorites found in Antarctica? Can humans reproduce on interstellar journeys? Why are we still looking for Atlantis? Why do we celebrate the discovery of new species but keep destroying their homes? Who will win the race to claim the melting Arctic—conservationists or profiteers? Why don’t travelers ditch Yelp and Google in favor of wandering? How did a 1961 conference jump-start the serious search for extraterrestrial life? Why are liminal spaces—where urban areas meet nature—so beautiful?

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.