In his defense of the recently revealed National Security Agency telephone surveillance programs, President Obama has also welcomed a national discussion about how to strike the balance between security and freedom. But this difficult balance, which has historically been negotiated through the give-and-take of politics and legal contest, may increasingly be turned over to nondemocratic, nondeliberative forces of technological innovation. In the process, one of society’s most powerful narratives of democratic struggle—the myth of the individual who rebels against social and political conformity—has been rendered implausible by the development of pervasive security technology.

Who can go on the lam anymore? Paying for car rentals, airline tickets, or hotel rooms with cash these days is almost itself an admission of guilt about something. The electronic economy pretty much eliminates the plausibility of any story that depends on everyday people getting voluntarily lost, and if you manage not to get caught at a cash machine or using your credit cards, then you might as well know that police departments are now routinely using devices that record the license plates of every passing car. And of course we now know that U.S. government security agencies have the capability of capturing everyone’s telephone activity. Whatever it is you’ve done, or whatever you’re trying to escape, if you’re not holed up in an off-grid hut in the north woods, like the Unabomber, you’re probably going to get caught.

The consequences are not just for the world we live in, but for the worlds we imagine. Today Marion Crane would have never been tempted by the office safe full of cash that allowed her to finance her road trip in Pscyho. For one thing, the idea of an office safe full of cash is no longer plausible—instead, Marion would carry a company credit card around. But she’d never think of using it for illegal purposes because she’d know she’d get busted. And even if she had stumbled onto a load of actual cash, investigators would have been hot on her trail the minute she tried to cover her tracks by buying a used car. Perhaps she would have still made it into the Bates Motel shower, but Norman Bates would have been safely behind bars shortly thereafter.

So far so good. If one consequence of making the world safer is that certain reliable plot devices are no longer plausible, that wouldn’t seem like anything to feel sorry about. But what happens in a society where ubiquitous technological surveillance makes it increasingly difficult to act outside of accepted social norms? What about Thelma & Louise, the movie in which two social revolutionaries fight oppression by taking the law into their own hands, defying social conventions about gender and law enforcement authorities alike as they go on a cross-country spree of free will? The balance of power between the individual and the system of law and surveillance in the early 1990s was such that Thelma and Louise are plausibly able to elude police long enough to choose their own fate, to exercise the ultimate agency and drive themselves literally off a cliff, the police still just one step behind. Recent developments in technology suggest that such an American expression of open-space, road-trip defiance is no longer possible in America itself. Defiance is possible, to be sure, but off-the-grid space is increasingly constricted in a world where our financial transactions, our telephones, and our automobiles give away our locations.

Today Thelma and Louise probably wouldn’t even make it out of town. Given the state of our surveillance technology, these two rebels would not get much beyond their first run-in with the law, their adventures recorded for the most part by the license plate readers and speed and surveillance cameras dotting American roadways and cities large and small. Or suppose they did somehow get away. Then imagine this final scene: With the smart/Web-enabled or Google driverless car of the future, law enforcement could have tracked every mile of their road trip, and, armed with the manufacturer’s “master password,” could have taken control of their vehicle by sending a wireless command to the car’s computer to “turn off ignition/lock doors.” Instead of having control over their fate and choosing to end it all in a final expression of autonomy, Thelma and Louise would end up trapped in their own car as the authorities circled in. A movie about defiance, freedom, and integrity would become, instead, one about the futility of individual rebellion and the inevitability of conformity.

We’re not condoning lawbreaking by free-spirited rebels, of course. Yet the good society is not one where everyone conforms to a set of norms and laws, but one where those norms and laws keep things in check, without enforcing absolute conformity. And just as laws help keep civil society in check without demanding mindless conformity, it’s equally true that the ability to push back against conformity is crucial for keeping state authority in check. Thelma and Louise weren’t real people, but they spoke to the need that we all have to believe that we are still free to rebel against the shackles of convention, and free to accept the consequences on our own terms.

The rebel who refuses to conform is a powerful democratic narrative, yet one whose plausibility seems to be under threat from the rapid advance of surveillance technology. How will our narratives of the future handle this change in today’s technological landscape? Bizarrely, what seems to be on display above all is a sort of denial of reality. A number of science fiction movies have actually had to “disinvent” existing technologies in order to retell the myth of how rebels against “the system” help preserve free and open societies.

In the film In Time, starring Justin Timberlake, technological advance in a distant future has brought immortality to humanity. But to prevent a population explosion, the longevity of some people must be limited by a capitalist clock. The more you earn, the longer you live. Time is added to the scan bar embedded in your forearm and linked to your heartbeat. Run out of money, run out of heartbeats. It’s a nice thought experiment about the future of a society obsessed with both wealth and longevity. Of course, a hero arises to confront the unjust system: Timberlake, who steals the heiress to one of the great robber barons of this future dystopia. But in the ensuing car chases and fight scenes, there is a complete lack of even the most rudimentary surveillance technologies that would quickly have empowered even a modest police force (not to mention that of the capital city where the film is set) to close in on this solitary revolutionary. What, a society that can control immortality but can’t track a criminal in a car? We bet O.J. Simpson wishes he had lived in that world.

Similarly, in the wildly popular teen film The Hunger Games, we see another dystopian high-tech world, but again, one where surveillance capabilities seem to predate present capabilities. In the unruly outlying provinces of this society, which verge on the edge of rebellion, control is exercised by storm-trooper-suited police, not much more technically advanced than those of 1930s Germany. Really? A hundred years in the future, and a dictatorial power that can contrive a global gladiatorial reality TV show can’t manage to monitor people in their homes? Our law enforcement and parole officials today use locator devices on any number of society’s troubled members. But a century from now, such technology or social control does not exist?

Amazingly, science fiction movies must posit a future that is less technologically developed than the present in order to allow a standard narrative of social redemption—the virtuous, solitary renegade—to remain plausible. We’ve seen a similar need for this sort of future anachronism in sci-fi movies like Enemy of the State, The Adjustment Bureau, and Total Recall. What are we to make of this denial of current reality as part of envisioning the future?

One paranoid possibility is that, in the desire to sell tickets, sci-fi filmmakers have unwittingly become part of the control mechanism. If sci-fi movies continue to perpetuate the myth that people of independent spirit will always find a way to rebel against the excesses of “the system,” then why rebel now against ubiquitous technological surveillance networks and their continued expansion into every crevasse of our lives? The necessary hero will come along to save us when the time is right.

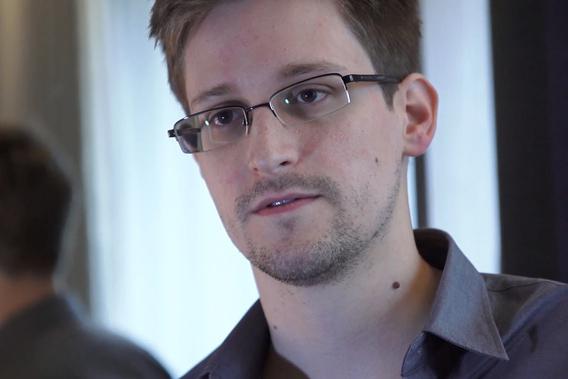

Like, in the mind of some, Edward Snowden, perhaps? Therein lies an irony, for he is hardly an ordinary citizen. Indeed, perhaps the most important lesson in the Snowden affair is that the rise of ubiquitous surveillance technology means that future rebels will have to be insiders with security clearances like Snowden. Or, in the world of science fiction, they will have to be super-expert technologists like the movie characters Jason Bourne or the rebels in The Matrix, who have the technical chops to evade and hack their way out of the security web.

And yet, if our narratives of rebellion against social and political conformity are plausible only when the rebels are security-state insiders and technological super-experts, shouldn’t we begin to wonder whether the future that such narratives are supposed to be warning us about has already arrived?

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter. The views expressed here are the authors’ alone and do not represent those of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, or the U.S. Naval Academy.