This article arises from Future Tense, a partnership of Slate, the New America Foundation, and Arizona State University. On Tuesday, May 7, at 9:15 a.m., Future Tense will host an event in Washington, D.C., on the use of drones in the United States. For more information and to watch the webcast live, visit the New America Foundation’s website.

Drones are coming home. For many years, we’ve used them to hunt and kill enemies in faraway places: Pakistan, Yemen, Libya, and Somalia. Now we’re deploying them in the United States, not to kill but to help with civilian missions such as land surveys, livestock monitoring, and search and rescue. But psychologically, the transition is hard. Like soldiers coming home from a war, we’ve become so accustomed to the mentality of combat that we’re having trouble adjusting to the idea of remotely piloted aircraft as a peaceful technology.

In recent months, drones have moved from the shadows of our national security debate to center stage. They dominated the fight over John Brennan’s nomination to be CIA director. Because of drones, protesters disrupted his hearing, and senators blocked his confirmation. But you don’t have to be a news junkie to feel the surge of alarm. Last year, in The Bourne Legacy, Hollywood brought us the specter of drone warfare against an American citizen, perpetrated not by a foreign enemy, but by our own scheming government.

The constant drone (if you’ll pardon that old-fashioned use of the term) of military chatter about remotely piloted vehicles has skewed our thinking about them. We see them as weapons. So we don’t like it when the discussion turns to using them in our own country. Among young people, drone has become a verb, synonymous with targeted killing. As the T-shirt puts it: “Don’t Drone Me, Bro.”

Polls reflect a consistent pattern: The more American the target, the less comfortable we are with deploying drones. In a February Fox News survey, the percentage of Americans who approved of drones declined precipitously as the suggested applications turned from foreign terrorist suspects overseas to U.S. citizens on American soil.

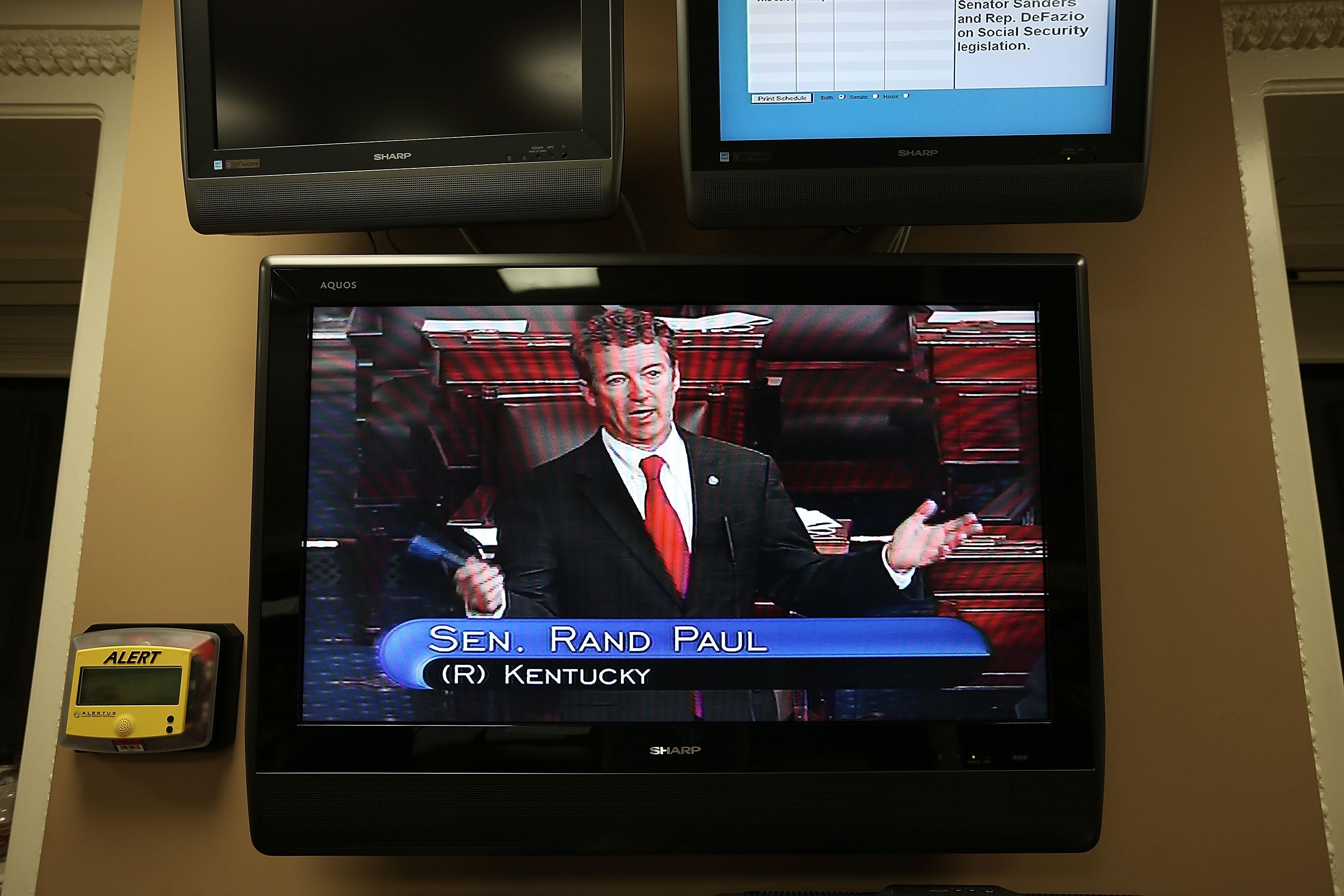

In the first week of March, Sen. Rand Paul transfixed the Senate with his paranoid filibuster about U.S. military drones annihilating ordinary Americans sitting in a café. The scenario was preposterous—it would be much easier for a corrupt U.S. president to kill you in a café using operatives on the ground—but it seems to have affected public opinion. By late March, when Gallup asked the same questions Fox News had asked, the percentage of respondents who favored the use of drones to hit suspected U.S. citizen terrorists on American soil had plunged from 45 to 13. Andy Borowitz, the political humorist, captured our feelings in a fake poll report showing that 97 percent of Americans strongly agreed with the statement, “I personally do not want to be killed by a drone.”

Within the U.S. population, you can see potential divisions over drones, driven by the same worry about who controls the technology and who might be targeted. When Fox News asked about the “United States” using drones to kill a suspected U.S. citizen terrorist on American soil, there wasn’t much difference based on race or party affiliation. But when the same survey asked about “the president of the United States, on his own” making the decision, big gaps opened up. Whites and Republicans sharply opposed the idea, while nonwhites and Democrats were more closely divided. Presumably, that’s because Democrats and nonwhites are more likely to identify with President Obama and trust him.

As the discussion pivots from military to civilian applications, some of these differences persist. A poll taken last year by Monmouth University found that within the U.S. population, there wasn’t much difference between racial and ethnic groups over the use of drones to track runaway criminals (which we overwhelmingly support) or to issue speeding tickets (which we overwhelmingly oppose). But when the poll asked about using drones to control illegal immigration on the border, again, a big gap opened up. Whites support that idea by a margin of 50 percentage points. Among Hispanics and blacks, the margin of support is much lower: 25 and 10 points, respectively.

Why the difference? Some of it may be that if you’re a racial or ethnic minority, it’s easier to imagine yourself as the target of a spy drone hunting illegal immigrants. And polls do suggest that the more easily you can picture yourself as a target, the more you worry about drones. Earlier this year, for instance, a Reason-Rupe survey found that while 32 percent of Americans worry “a lot” about U.S. drones hunting suspected citizen-terrorists, 40 percent worry “a lot” that their local police department might use spy drones to invade their privacy. The latter scenario feels more personally plausible.

Will our fear of drones subside as we become more familiar with them? That’s what polls have suggested in the context of military applications. The March Gallup survey, for example, showed that Americans who have closely followed news about drones are significantly more likely to support the use of these weapons to strike suspected terrorists—regardless of the suspect’s citizenship or the location of the strike—than are American who haven’t paid much attention.

But that pattern doesn’t hold for domestic applications. According to the Monmouth University survey, Americans who have read or heard a lot about military drones are more likely than other Americans to support the use of drones to control illegal immigration, but they’re less likely than other Americans to support the use of drones to track down criminal fugitives or issue speeding tickets. Learning more about drones doesn’t make you love them. It just makes you realize how good they are at what they do, even when you’re the target.