In the status update age, it may be hard to believe, but not every aspect of technology should cater to you and your experience. Museums are especially vulnerable to the dangers of user-centrism, and pressure is increasing for them to embrace the experience economy by offering interactive exhibits that “come alive.” Sure, visitors are learning and having fun, but in the long run, this attitude may threaten the durability of collections—you know, the reason why you go to the museum in the first place.

Today’s museums give the entertainment industry a run for its money. According to the Horizon Report: 2011 Museum Edition—a joint effort between the Marcus Institute for Digital Education in the Arts and the New Medium Consortium—there’s an all-out digital love fest going on. In the near-term, its authors expect extensive efforts to focus on mobile apps. In the next two to three years, they predict “wide-spread adoptions” of augmented reality. Four to five years down the road, emphasis should shift to digital preservation (looking for ways to “future-proof” digital objects) and smart artifacts that “blur the line” between digital and physical things.

To get a sense of whether the digital turn will live up to the hype, we went off to see “Spy: The Secret World of Espionage” at Discovery Times Square in Midtown Manhattan. Although the venue is branded as a “more than a museum”—presumably because it offers shows that assault the viewer with titillating technology—we prefer to see it as a magnifying glass that can illuminate potential museum pitfalls.

As history geeks, we think declassified CIA artifacts are cool. Who wouldn’t be psyched to “encounter real declassified gadgets revealed for the first time ever from the world’s leading intelligence agencies”? A 1960s shoe with listening device in the heel? Awesome. Hollow nickels with poisoned needles? Right on. A massive old-school CIA camera flown around by pigeons? Wish they starred in an animated series.

Unfortunately, the experience was a big letdown. Prior to seeing the artifacts, we had to watch two video displays designed to prime the audience for what’s ahead—videos that would have been better suited for home viewing on YouTube. This strategy backfired, and we each had the same thought: “Plenty of videos exist online. What a waste here.” As we made our way past interactive screens containing information that also could have been archived online, the thought recurred.

Museum scholars have noticed this problem, too. Dirk vom Lehn, a sociologist at King’s College in London and member of the Work, Interaction and Technology Research Centre, and his colleague Christian Heath study how people interact with and around technology when they’re at museums. They’ve observed many instances of digital seduction, in which visitors focus on hand-held computer screens and touch screens at the expense of both original objects and social interaction.

One solution identified by vom Lehn and Heath is for museums to use technical systems that direct visitors toward genuinely social situations. Take Launch Pad, an interactive gallery at the Science Museum in London. It stimulates collaboration by presenting material that groups can not only watch together, but also collectively explore.

If done well, technologically inspired group interactivity can go a long way to giving visitors a sense of purpose—that they are experiencing something important that home browsing doesn’t make available. That can help mitigate Arianna Huffington’s concern that giving social media pride of place in museums can diminish curiosity and discovery.

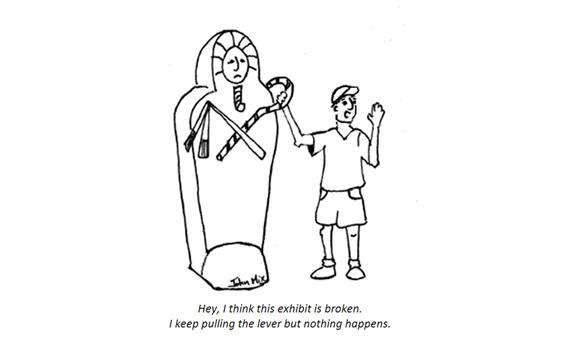

Cartoon by John Mix.

But interactivity isn’t an end in itself when it is presented as “some eternally present, unceasingly entertaining, Chuck E. Cheese-like arcade,” as philosopher Justin Erik Halldor Smith has fretted. At the spy exhibit, we were subjected to a cheesy smoke and laser challenge—stumbling over simulated tripwires and learning nothing in the process. Barney Stinson of How I Met Your Mother would find the razzle dazzle legendary. But he’s a fictional character, and a shallow one at that.

The Horizon Report notes that modern museum-goers won’t accept being viewed as passive receptacles of knowledge deemed important by curators and museum educators. Accustomed to Google and Twitter, they embrace democratized knowledge and are ready to “find, interpret, and make their own connections with collections and ideas.” But the curators of the spy exhibit must have missed that memo, because while they focused on threats to the state, they failed to spend any time on one of the most pressing issues of our time—surveillance of average citizens. Time will tell if the presence of tech that sparkles instead of sparking inquiry will make it easier to distract visitors who are satisfied to see artifacts detached from politics.

One more wrinkle should give museum fans pause. In order for museums to honor their institutional commitment to housing original objects for research purposes, they must foster concern for artifacts that extends beyond their educational and entertainment value. Otherwise, future generations—including historians—won’t be able to access invaluable material. Keeping the wow factor up can be expensive, and if opportunity costs arise, it might seem sensible to sell off archived works that aren’t crowd-pleasers, or, worse, let them dissolve into the abyss of neglect. Razzle-dazzle simulations that can be saved on tiny hard drives could appear more desirable than larger, vulnerable analog collections.

To safeguard against this possibility, museums need to do a better job at reminding patrons of their full mission. When telling an artifact’s story on a label or on a tour, a guide could share a few words about its recent history—how it was acquired and restored, what it takes to keep it safe. Perhaps even before entering an exhibit hall, visitors could be told why the room is cold or lights so low.

Go to museums—have fun, be amazed, and, by all means, learn something. Most importantly, be impressed by the presence of some pretty awesome things even if they don’t light up or move, and appreciate the commitment required to safeguard this presence for others.

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.