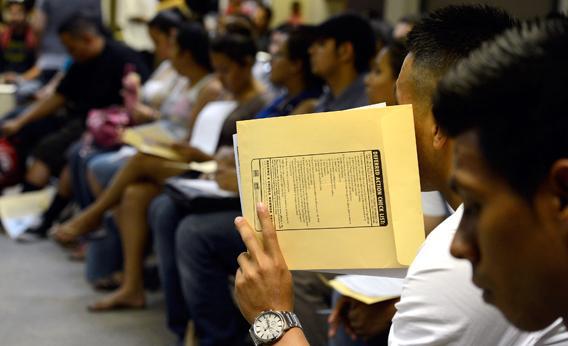

Given the images of people lining up in cities across the country to attend workshops on the so-called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program for DREAM Act-eligible kids—which allows teenagers and young adults who were brought to the United States illegally as children to remain in the country without fear of deportation—you might think that spreading the word about this opportunity is akin to hawking tickets to a Justin Bieber concert. That is, even a rumor will make the masses come running.

But figures released by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services show that at this point, just 82,000 immigrants, a small fraction of the 1.2 million estimated to be currently eligible for the program, signed up. According to Luis Arbulu, a former Google executive who has served as an entrepreneur-in-residence for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration, the kids who queued on Aug. 15—as soon as government started accepting applications—are the super motivated. “They are the ones,” he says, “who get their college applications in on the first day.”

But what about the hundreds of thousands of other teenagers and young adults? For that, immigrant advocacy groups are gearing up for a mobile technology campaign that would impress the savviest of Madison Avenue’s social media mavens. Advocates will leverage texts, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, because the bulk of those eligible for Deferred Action are between the ages of 15 and 31, arrived before they turned 16, and have spent at least five years in the United States.

It doesn’t begin and end with the trendiest technology, though, because immigrant activists’ target crowd goes beyond the young and Internet-savvy. The executive order is pretty expansive: While the DREAM Act legislation that Congress voted down several times would have required immigrants to have completed at least two years of college or enlisted in the military, the president’s initiative includes residents who have obtained a GED or are in some kind of vocational training. As a result, according to a National Agricultural Workers Survey, some 54,000 farm workers could qualify if they find a way to get into a classroom. This is a group that isn’t on Facebook, at least not every day, so activists will need to find other ways to reach them.

In addition, about one-quarter of the immigrants who could take advantage of the deferred action can’t yet, because of the “at least 15” mandate—some who might be eligible in the future are as young as 5. So getting it on the radar of their parents and other “influencers” in their lives is vital. This assumes, of course, that the Deferred Action program will continue in the years ahead, which isn’t a guarantee. It doesn’t provide lawful status but rather a two-year reprieve, and subsequent administrations could revoke it.

That said, there is a real payoff from registering: Successful applicants won’t just be free (for now) from perpetual threat of getting kicked out of the country, but they will also receive permits to work in the United States. In some states, too, those who register will be eligible for in-state tuition and drivers’ licenses.

Convincing the DREAM Act set to apply isn’t so different from marketing any product to 18- to 25-year-olds, albeit with a big exception: Smartphone apps are off the table. Because DREAM Act kids are by definition undocumented, the vast majority of them—and their parents—aren’t going to have credit cards, which means phones that require long-term contracts are out. They’re most likely to use pay-as-you-go phones instead. But even less-than-smart phones allow for SMS texting, which is by far the most effective way to reach young people. “They don’t check their email,” says James Citron, the founder and chief executive of Mogreet Inc., which advises companies on texting campaigns. “But they are addicted to their cellphones. Texting is the way most of them talk to their friends”—so it’s also the most efficient way to get their attention.

The challenge is obtaining cellphone numbers: Federal legislation and Federal Communications Commission rules require that people request the texts, or opt in, before receiving them. That’s why when you log on to weownthedream.org (a website launched by advocacy groups including United We Dream and the National Immigration Law Center that features webinars and information about local clinics on the Deferred Action program), the one requirement to receive news alerts is your cellphone number. Your name, address, and email address are all optional.

Then there’s Facebook. Being undocumented often feels shameful—kids who know they are in the country without authorization are generally loath to talk about it with their peers. The Internet provides a safer place to find a community and congregate. “For a lot of these kids, online was the only place they could talk about what they were going through,” says Adam Luna, political director of America’s Voice, an advocacy organization based in Washington. In addition to posting messages on its Facebook page, the organization is planning—budget permitting—to purchase paid ads on the network in the 200 ZIP codes with the highest concentrations of Latino and Asian residents. Those metrics aren’t arbitrary: A whopping 85 percent of those eligible for Deferred Action are either Latino or Caribbean, and 9 percent are Asian, according to a study conducted by the Migration Policy Institute.

Activists are also crafting public service announcements that have been posted on advocacy groups’ websites and YouTube. Those at national organizations are counting on DREAMer activists to link to the videos on their Facebook pages and pass the PSAs on to local radio stations.

While the Web is a centerpiece of the campaign, radio, TV, and print all factor in as well. Latinos, the primary target group, are generally more likely to listen to the radio than people of other ethnicities. And communicating through that medium will catch men and women who can’t be reached via cyberspace: According to a 2011 study, merely half of the listeners of Latino news and talk shows have online access.

In the effort to reach DREAMers, the activists will be facing some competition from so-called notarios and unscrupulous attorneys who are soliciting fees to “guide” immigrants through the application process. Google Deferred Action, and the paid ads that crop up almost uniformly require some kind of payment for help, even though that guidance is available through sites like United We Dream free of charge. Part of the campaign will be to steer applicants away from those seeking to take advantage of them. Investigating which of these organizations are just usurious versus downright criminal would be time-consuming, if not impossible. So rather than try to shut down the bad actors, advocacy groups are launching sites like Stop Notario Fraud to educate immigrants about predatory groups.

Immigrant activists haven’t embarked on an outreach campaign of this scale since the 1986 reform, which included an amnesty program that ended up making 2.7 million illegal immigrants citizens. Identifying and coaxing teens and young adults to register for the Deferred Action program won’t be easy, in part because so many of these immigrants are accustomed to hiding their status. Still, activists who came of age after the 1986 reform in particular seem eager to get to work. Adam Luna of America’s Voice started his career campaigning against California’s Prop 187 referendum in 1994, which would have—among other provisions—barred undocumented immigrant kids from attending public schools. More recently, he’s organized against mass deportations and the recent Alabama law that made it illegal for undocumented immigrants to rent a house, pay a utility bill, or even sign a contract. Against that backdrop, the Deferred Action program feels like a new, and welcome, chapter. “For the first time in my career,” he says, “I can organize for something,”

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.