On Super Bowl Sunday, Jan. 22, 1984, Apple ran one of the most famous TV advertisements of all time. It opened with a gray theater full of people with shaved heads, wearing gray jumpsuits, staring expressionlessly at a large screen. From the screen, an Orwellian “Big Brother” intoned, “We are one people, one whim, one resolve, one course. Our enemies shall talk themselves to death, and we shall bury them with their own confusion. We shall prevail.”

As he spoke, a blond woman ran into the theater, bearing a sledgehammer. She threw it at the screen, and the screen exploded. An off-camera voice declared, “On Jan. 24, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like 1984.” Today, more than two decades later, the message remains tremendously powerful: Innovative technology in the hands of brave people can free us all from tyranny.

Fifteen years later, in the fall of 2009, Apple officially launched the iPhone in China in partnership with a domestic mobile carrier, China Unicom. As a condition for entry into the Chinese market, Apple had to agree to the Chinese government’s censorship criteria in vetting the content of all iPhone apps available for download on devices sold in mainland China. (Most apps are created by independent developers— individuals, companies, or organizations—and then submitted to Apple for approval and inclusion in its app store.) On Apple’s special store for the Chinese market, apps related to the Dalai Lama are censored, as is one containing information about the exiled Uighur dissident leader Rebiya Kadeer. Apple similarly censors apps for iPads sold in China. So much for that revolutionary, Big Brother-destroying Super Bowl ad. Apple seems quite willing to accommodate Big Brother’s demands for the sake of market access.

Companies like Apple, Facebook, Google, and many other digital platforms and services have created a new, virtual public sphere that is largely shaped, built, owned, and operated by private companies. These companies now mediate human relationships of all kinds, including the relationship between citizens and governments. They exercise a new layer of sovereignty over what we can and cannot do with our digital lives, on top of and across the sovereignty of governments. Sometimes—as with the Arab spring—these corporate-run global platforms can help empower citizens to challenge their governments. But at other times, they can constrain our freedom in insidious ways, sometimes in cooperation with governments and sometimes independently. The result is certainly not as rosy as Apple’s marketing department would have us believe.

Apple’s iNation

Apple’s censorship problems reach well beyond China into unexpected places. In March 2010 Apple shut down, without notice, an iPad application for Stern, one of Germany’s biggest magazines. It had published erotic content in the printed magazine, which was automatically duplicated in the iPad app. This content is perfectly legal in Germany, but because some pages of a specific issue were deemed in violation of Apple’s app standards, the entire magazine was censored through the app store. Apple told another German magazine, Bildt, that it had to alter content if it wanted to keep its app.

That year Apple also censored a cartoon version of James Joyce’s Ulysses that contained a few images of nudity, despite the fact that the app had been marked as containing adult content. The app was eventually reinstated, but only after a massive public outcry and widespread media coverage. Apple also censors controversial political and religious content, including several apps featuring the work of Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist Mark Fiore because they “ridiculed public figures.” His app mocking President Obama—containing the type of political humor frequently seen on television and in newspapers—was restored soon after Fiore won his Pulitzer. But other cartoonists and satirists were not so fortunate.

In response to widespread controversy over app censorship, in late 2010 Apple publicized its app review guidelines and established a review board so that developers would have a more systematic way to appeal decisions made against their apps. But censorship complaints have continued, from both the left and the right of the American political spectrum.

Facebookistan

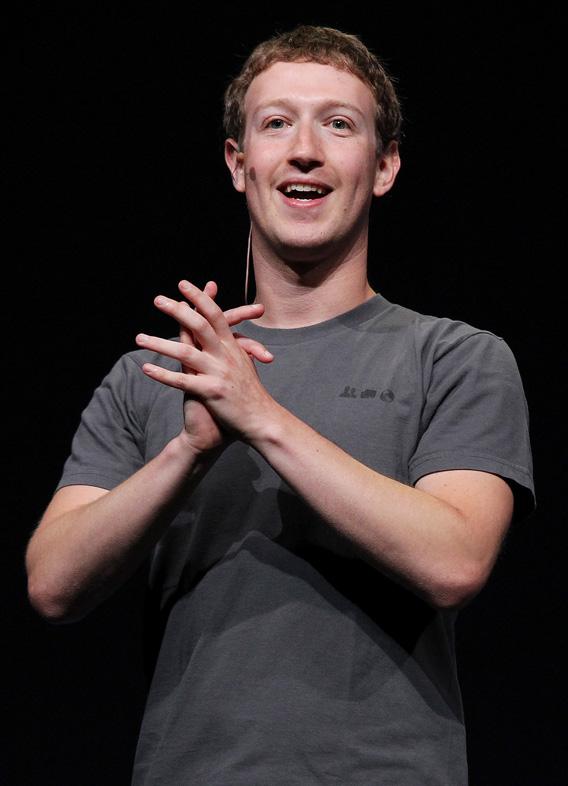

More than 800 million of people “inhabit” Facebook’s digital kingdom. If it were a country, it would be the world’s third largest, after India and China. Call it Facebookistan. It is governed by a set of rules based on an ideology espoused by its management team and “founding father,” who govern their kingdom as they believe is in their users’—and their own—best interest.

Zuckerberg advocates what has come to be known as “radical transparency”: the idea that humanity would be better off if everybody were more transparent about who they are and what they do. Anonymous online speech runs directly counter to this ideology. He has said that people who do not reveal their true identities online “lack integrity.”

The Facebook terms of service, to which every user must click “agree” to create an account, require that all inhabitants of Facebookistan use their real names. Accounts using pseudonyms or fake identities can be punished with suspension or deactivation. This internal governance system spans physical nations, across democracies and dictatorships.

This can be problematic for anyone in a democracy who engaged in political or social activism that their employers or potential employers might disapprove of, even when they do so on their own time.

Activists using Facebook in repressive regimes are in a position many magnitudes more difficult: They can use fake names and risk having their accounts deactivated. Or they can use their real names and risk arrest—and worse. Events in Egypt leading up to Hosni Mubarak’s fall underscored this problem. On the one hand, Egyptian activists—including, most famously, the Google executive Wael Ghonim—were able to use Facebook in late 2010 and early 2011 to create a viral human rights and anti-torture campaign that helped bring people onto the streets. On the other hand, they had to violate Facebook’s rules in order to do so: Ghonim and the others all used pseudonyms in order to avoid going to jail.

On Nov. 24, 2010, the day before a long-planned Friday of protest in Egypt, the key Facebook page for this human rights campaign hit its peak of activity as more people joined, members traded information, and organizers sent out updated instructions. Then suddenly, without warning, the page disappeared from view. Its creators received a notice from Facebook staff that they had violated terms of service that require administrators of pages to use their real identities—and furthermore, that accounts of people not using their real names, when discovered, would be shut down. Coincidentally, this all took place while the Palo Alto, Calif., Facebook headquarters were observing Thanksgiving.

The page’s creators were fortunate to know people working in Silicon Valley and for international human rights groups, who contacted Facebook executives. It was restored in less than 24 hours, but only after administrative rights for the page were handed over to Nadine Wahab, an Egyptian woman living in Washington who, unlike the activists in-country, was willing to verify her true identity with Facebook staff.

Nobody is forcing anybody who is uncomfortable with the terms of service to use Facebook. Executives point out that Internet users have choices on the Web. But for activists trying to maximize their impact, Facebook’s global dominance means that many activists can’t afford not to be on it if they want their movement to succeed, despite the risks. “If you want to organize a movement the only place to do it effectively is on Facebook, because you have to go where all the people are,” Wahab told me shortly after taking over the account.

Googledom

Google’s new social network, Google Plus, started with the same governance philosophy as Facebook as far as identity is concerned, but has proven to be more flexible and open to lobbying by users. In July 2011, roughly a month after the launch, administrators began to deactivate accounts registered under fake names and pseudonyms en masse. The reaction from privacy and civil liberties groups—as well as prominent members of the technology press—was sharply critical. Google Plus members even used the platform’s own features to organize against its identity policies.

Then in November 2011, Google announced that it would create new procedures for people to use nicknames and pseudonyms, at least in cases where people have an established online identity different from the name on their government-issued ID. In January 2012, Google Plus started to roll out support for nicknames and pseudonyms, but those registering with a name other than their real-life one must be able to prove that they have been using that alternative name elsewhere either on the Web or in real life.

Managers and product developers—the barons and lords of Facebookistan, Googledom, the Apple iNation, and other platforms—have been thrust into governance roles that they are for the most part unprepared for, leading to real-world political consequences that they do not understand and have trouble anticipating. They have not yet figured out how to govern their private platforms in a way that is genuinely compatible with democratic ideals and aspirations of many of their users in the physical world.

They have also been thrust into the realm of geopolitics. The new digital sovereignties have begun to clash with conventional nation-states. A classic example was Google’s clash with the Chinese government. In March 2010, Google stopped censoring its Chinese search engine, Google.cn, and moved it out of mainland China in response to aggressive and sustained attacks launched from Chinese computer servers on Google’s Gmail service a few months before. The Chinese government denied knowledge of or connection with the attacks, denials that security experts and Western diplomats found difficult to believe, given the attacks’ military-grade sophistication. Gmail also happened to be the email service of choice for Chinese dissidents and activists.

If Google was not going to obey censorship orders and respect Chinese law, officials said, then good riddance. Yet in the end, Google was not fully banned from China. It retained its license to keep a business presence in China and continued some activities not related to search: Android mobile phone operating system development and support, advertising sales, plus research and development for future products.

The reason has to do with Google’s own Chinese constituency: people who need access to at least some of Google’s products and services to do their jobs and build their own innovative businesses. As the Chinese blogger Michael Anti commented to me wryly at the time, “Google is much more popular in China than the USA.” Almost no Chinese citizens consider themselves stakeholders or constituents of the United States. But Google has many Chinese constituents. They are, in effect, digital residents of Googledom: a global community of people who rely on certain Google services.

Trust but Verify

In late 2010, Google CEO Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen (who had just left the State Department policy planning staff in the summer of 2010 to run Google’s new policy think tank) published an article in Foreign Affairs outlining their geopolitical vision for a digitally networked world. “Democratic governments,” they wrote, “have an obligation to join together while also respecting the power of the private and nonprofit sectors to bring about change.” They warned against overregulation of Internet companies, lest their greatest value to citizens be stifled.

That is certainly a valid concern. But if the sovereigns of cyberspace are to avoid counterproductive government interference, they must do more to bolster their own legitimacy and earn the trust of their constituents. The first step is to make commitments—akin to the constitutional commitments of governments—to govern their digital worlds in a way that is compatible with the same universal principles on freedom of expression, assembly and privacy that make democracy possible.

As with physical sovereigns, the sovereigns of cyberspace must be held accountable to their commitments in order to be credible, and ultimately to be successful. As Ronald Reagan once put it: “trust but verify.” They must be much more transparent about how their policies are made and how they conduct their relationships with governments; they must open themselves up to enough external scrutiny to verify that they are not deceiving people; and finally, they must engage constructively and systematically with users and customers who harbor concerns.

If the sovereigns of cyberspace do these things, the public will trust them—and that confidence will have been well-earned. This trust will in turn give them legitimacy to act as a welcome counterweight to government sovereignty: holding one another in check, making the abuse of power—be it by the sovereigns of cyberspace or the sovereigns of the physical world—more difficult.

Adapted with permission from Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle for Internet Freedom, by Rebecca MacKinnon. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2012.

This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.