This article arises from Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, the New America Foundation, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.

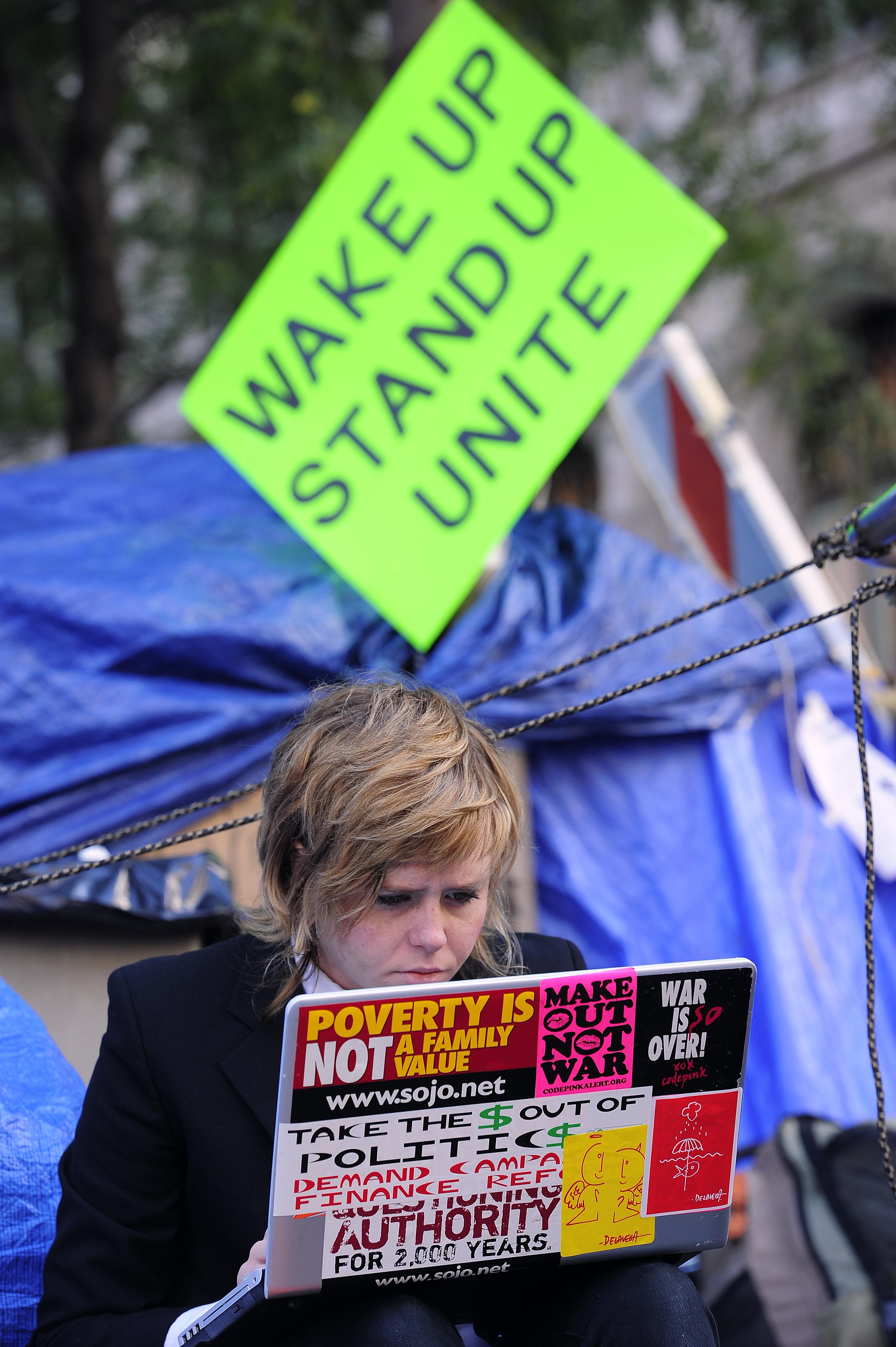

AFP/Getty Images

For the most part, media coverage of the Occupy Wall Street protest has been predictable. Stories are narrated according to the pro/con structure typical of—depending on whom you ask—balanced reporting or sensationalism. On the one hand, positive focus sympathetically explains why protesters have been demonstrating en masse since Sept. 17. These accounts place the activist mantra of “We are the 99%” in a historical and economic context that connects significant inequalities in wealth to violations of justice that should prompt people of conscience to demand rectification. On the other hand, negative reports argue against interpreting the protest as legitimate civil disobedience. Detractors’ opinions range from indictments of individual work ethic—contending that that problem at issue is poor individual decisions, not dysfunctional systems—to indignation over an unclear protest agenda that allows Dionysian energy to manifest in this millennium’s Woodstock.

Because we’re ethics instructors, people inevitably ask us to make sense of headline-grabbing protest stories. In most cases, we apply ethical theory to the circumstances at issue. For example, when protests occur over drone airstrikes, we direct attention to just war theory. However, when queried about Occupy Wall Street, we respond differently. Our attention turns to themes related to collective action. In problems of collective action, individuals who work solely for their own selfish interests can bring about tragic consequences for society as a whole. The only way for collective action problems to be solved is to create coordinated collaborations that unite social and individual interests. The “collective” element is paramount because even one “defector” (someone who acts selfishly, like those who stand accused of criminal acts at Occupy Wall Street camps) has the power to ruin everything by leading others to defect as well.

Occupy Wall Street is an especially interesting collective action movement because it embodies a distinctive and pervasive shift in ethical orientation. The long-simmering forces that gave rise to the protests also have profoundly altered how students today view their place in society. Although we teach at different universities, recently developed information and communication technology allowed us to create an innovative cross-university model of education that jointly immerses our classes in games that present collective action problems. Before saying more about the games, it will be helpful to explore the parallels uniting streets and classroom.

The economic formulae that dominated the “bubble” economies of the last two decades embodied lamentable values. Regardless of asset class (Internet stocks, fiber optics, fuel cells, corn ethanol, Ponzi schemes, or housing), bubble speculators could succeed only by advancing their own positions at the expense of the greater sucker whom they imagine will buy at even more inflated prices. Bubble speculation is a case of greedy people attempting to take advantage of people they think are even greedier. The resulting misallocation of capital is long-lasting, deleterious social consequences with handsome profits for the prescient few that got out of the game early or could skim exaggerated commissions from well-timed transactions.

The housing bubble—the biggest of them all—has touched nearly all Americans in some personal way, carrying with it an undeniable sense of complicity. There were the bankers who intentionally invented mortgage-backed securities and derivatives that could not be priced to market; the ratings agencies that rated new financial engineering instruments as top-quality rather than the junk that they were; and homeowners who falsely stated incomes and took no-doc, no-principal, floating interest rate mortgages they couldn’t possibly afford. Government officials not only encouraged the housing bubble with monetary, fiscal, and regulatory policies; they also downplayed the crisis until it was so far out of control that emergency powers were used to attempt to avoid a complete economic collapse.

The days of individualistic egocentrism, which characterized the long economic boom following the savings-and-loan crisis of the early 1990s, are over. They have been supplanted by the moral principle of the greater good. We’ve gone from Gordon Gekko’s “Greed is good” to John Nash declaring in A Beautiful Mind, “Adam Smith was wrong!”

Significant ethical transformation, especially at a large scale, is rare. The new ethical orientation brought into relief by Occupy Wall Street didn’t arise because media coverage of the busted bubble brought injustice to society’s attention. Instead, catastrophic consequences touched people personally, and emotionally intense experiences centering on loss, political despair, and outrage over the lack of shared sacrifice, fostered a new solidarity that manifested in a new identity (“We are the 99%”). Much as we might like to believe that citizens agitate for moral change as soon as they become aware of injustice, the fact is that they often don’t. This is especially the case if agitation requires more than token gestures, such as signing petitions, making small donations, using political bumper stickers, or “liking” Facebook pages. Back in ancient Greece, Socrates claimed that to know the good is to do the good. Alas, he was wrong—as are those who follow in his footsteps and believe that a well-informed citizenry is inherently a morally responsible populace.

In traditional ethics instruction, students learn to separate right from wrong, virtuous from vicious character, and a host of meta-ethical theories (deontology, utilitarianism, virtue ethics, etc.) by reasoning through examples of moral failures. Through inferences, analogies, and imaginative considerations, students identify personal duties and professional ethical expectations. But we have found this entrenched pedagogical method causes two problems: 1) Students become quick to label others who commit morally questionable actions as bad apples in what would otherwise be a good barrel of humanity; and 2) they overestimate their own moral fortitude. They see themselves as capable of rising above the temptations that sent the bad apples astray.

In 2005 we set out to correct these problems by introducing experimental exercises that ask students to put their moral commitments to the test through action. With subsequent funding from the National Science Foundation, we developed games that require students to grapple with some of the problems of neoclassical economics that relate to sustainability. Each game places students in game-theoretic situations (e.g., the classic prisoner’s dilemma) that require them to consider what extent they are willing to advance their own position in the game at the expense of their classmates.

The first game we developed demonstrates the problem of environmental externalities. The students play the role of industrialists. They are assigned to groups that produce luxury (cars), intermediate (appliances), and subsistence (food) goods. Each student must decide how much to produce, knowing that the more she produces, the more profit she can make, which will be reflected in her grade. Luxury players can make the most profit; subsistence player can make the least. But, of course, production also results in pollution. Whereas the profits improve grades of individual players, the pollution, which is calibrated to mirror the exponential damage found in the real world, subtracts from the grades of all players. Each student has an individual incentive to overproduce, while the best outcome socially is to curb production. The other games pose similar problems of cooperation and collective action. After students select their decisions or instructions, we model the outcome of the simulation.

In the first five years of testing our instructional games, a predictable pattern occurred repeatedly. The unchecked greed of a few precipitated class-wide moral questioning and was followed by redemptive behavioral changes that occurred after we granted their tormented requests to be given replay opportunities. We call this the identity crisis, and we hope that it, like the catastrophes that incited Occupy Wall Street, will help students better align their values and actions.

This term, we have observed something remarkable and new. Students are far more willing than their immediate predecessors to work collectively for the success of the class in their first attempt. Even greedy players, who are fewer in number this year, fail to precipitate the “everyone for themselves” mentality that results in tragedy. In fact, the 2011 students are more willing to forgive betrayal, negotiate with unscrupulous actors in ways that create remorse, and prompt remedial actions to correct the injustice.

To determine whether our students’ change was an outlier, we duplicated the game experience at several other colleges, where play took place within the classroom. We further recruited instructors to use EthicsCORE, a collaborative online resource environment, to offer blended learning (played partly in class and partly online) and wholly online versions of our games. These formats enable students from different universities to play together, without being in the same class. The students took part in a game called Pisces, in which they join simulated fishing groups and have to make decisions related to investment and consumption. Game play scores get converted into real quiz grades, and quiz grades are determined by how students interact with an extended class containing members known only online. Emotions can run so high that students check their smartphones throughout the day to get updates on how game play and the discussion surrounding it are going.

At first, we weren’t sure if students could set aside the incentive to lie, cheat, and steal from one another, and work collectively online. While such technology can allow for meaningful connections, the conversations it permits are different from face-to-face interactions. As anyone who has ever left an angry comment on a website knows, people speak more freely and with less concern for consequences while online. EthicsCORE allows students to communicate anonymously as well as though unique identifiers, and we presumed the anonymous function would be used to cause trouble. We also speculated that tribalism associated with university pride would incline students to give preferential moral treatment to fellow classmates, partially due to their immediate presence, and expected that on a larger scale, the apparent improvements in moral behavior we had seen would revert to the baseline of previous years.

The results have been uniform. Today’s college students exhibit a greater disposition to work collectively than students did just last year, or in the previous five years. They may not be camping out to protest publicly, but the forces that gave rise to Occupy Wall Street surely have influenced their ethical sensibilities.

We view both the Occupy Wall Street and the change of behavior in our classrooms as resulting from the shared experience of the Great Recession. However, we also anticipate that so long as catastrophic conditions persist and create large-scale, personally experienced effects, new movements are likely to emerge. This should give us profound pause. Collective action can be nonviolent or violent (as in the case of the London riots), benevolent or malevolent, constructive or destructive. The future of political action in the United States may not be as benign as the recent past or present.

Evan Selinger is an associate professor of philosophy at Rochester Institute of Technology. Thomas Seager is an associate professor at the School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment and a Lincoln fellow of ethics and sustainability at Arizona State University.

The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.