Thanks to the revelations that Hillary Clinton used her own private email server while secretary of state, and then may have erased more than half of them before releasing those missives to the public, we’re having a national debate about government officials and their email. The Associated Press is suing the State Department for her messages, while Republicans are calling for her to testify in Congress.

Still, I can’t help but feel that the strange details about yoga routines, personal servers, and the forensic analysis of classified data packets are distractions. This is a legitimate scandal and an important debate, but it’s also a limited one: If we really feel all federal employees’ communications need to be archived as a matter of the public interest, we need to be talking about a lot more than email.

Full-time staff working within the State Department all have state.gov email accounts. They’re also issued BlackBerries because of the long-standing viewpoint of the federal government that the devices offer the best high-level security for email and instant messaging. When a staffer uses her state.gov email, she needs to use an approved government computer, which requires special passcodes and software, or she must tackle the cumbersome interface of her government-issued BlackBerry.

When Hillary Clinton was secretary of state, a law and a regulation—the Federal Records Act and Section 1236.22 of the National Archives and Records Administration’s Electronic Code of Federal Regulations—most likely required that official emails sent and received by Clinton needed to be archived. Legal experts, politicians, and journalists can certainly parse what constitutes an official email and whether the personal email server Clinton used was appropriate given her position.

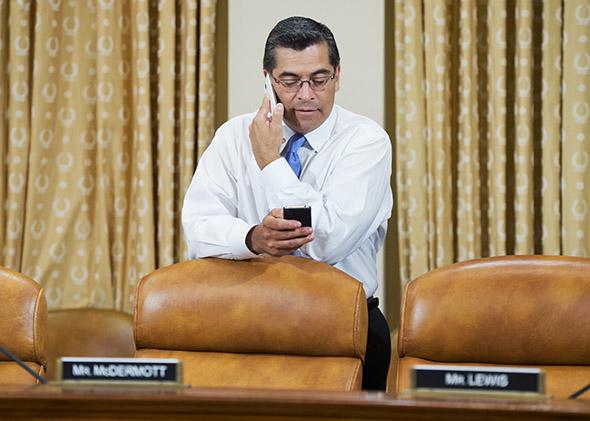

And yet, while Clinton was at State, staffers—not just hers, but employees throughout the federal government—were conducting official business on the go, because like employees in every modern workplace, they increasingly rely on mobile phones to do their duties. They might write emails on their work phones or use BlackBerry Messenger, but other times and for reasons of convenience—perhaps it was easier to type with one hand while walking, or it had better cell coverage in a particular area—government staff and leaders almost certainly used their personal devices. Without doubt, someone, somewhere at the State Department used his personal iPhone to ask his counterpart at the White House to push back a meeting 15 minutes. An aide to someone in the House used her own phone to text about the status of a bill or the result of a meeting with another lawmaker.

These are the kinds of communications previously relegated to email and ostensibly subject to archive and review. But we don’t live in an exclusively email-based world anymore. In 2012 the White House even launched a Bring Your Own Device to work initiative for federal agencies. While State Department staffers are supposed to use BlackBerry Messenger for short text messages, many other departments are starting to use other devices and different text-messaging apps.

It would be impossible to calculate, in any precise way, the volume of official government business now conducted outside of the officially sanctioned email or hardware system. But we can try: Forty-five-year-old cellphone owners send a median of 10 text messages a day, while 28-year-old texters send a median of 40. And these are regular people, not the hyperconnected denizens of federal Washington. There are tens of thousands of people working at the White House, in the executive agencies, and within Congress. It isn’t hyperbole to say there are probably a few hundred thousand text messages being exchanged among government officers, elected officials, and staff each and every day—many of which will escape the net of federal archiving requirements.

One problem with trying to collect more texts: Most SMS text messages aren’t necessarily archived. Mobile carriers keep records of phone use, and they log calls, text messages, and photos sent from one phone to another. Usually carriers keep a backup of a phone’s messages, but only for a few weeks at most. Is the government’s mobile carrier permanently archiving all BlackBerry Messenger and other text messages sent to, from, and among staff, agency heads, and elected officials? It’s possible. And theoretically, government leaders and staff can manually archive their personal phones’ text messages, if they know how. But this would need to include each and every new chat thread, and it would need to be uploaded using a common labeling system to a big database somewhere for review. That archiving effort would be insanely difficult. But not as difficult as the real-time organization of that data so that later, someone could search and retrieve an archived text and a particular subject and still know who sent it.

Federal law complicates the matter further: Phone records are private if the phone and account are registered to an individual. That’s to protect a third party–the person with whom you’ve been communicating, because she has privacy rights, too. Even if the government were to archive all texts sent from nongovernment devices, could the law even apply to messages sent from personal devices to journalists, constituents, and, say, yoga teachers?

What’s more, text messages and email are only part of how government staffers communicate digitally. Well after Clinton left her post at the State Department, some government workers started to use Slack, the hybrid email/instant message service that’s becoming popular throughout many workplaces. Slack allows users to share messages on computers and mobile phones, and it enables document uploads as well. The paid version of Slack archives content at Amazon’s AWS data centers. Theoretically, there is a way to export private and group messages that might include any edits made to messages, but to meet the same standards as government email, reports would have to be continuously synced and exported—it’s a difficult technological feat.

So why are we just talking about email? It might have something to do with high-profile lawmakers who came out this week saying that they rarely use it. New York Sen. Charles Schumer told the New York Times that he sends an email message “maybe once every four months.” Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina admitted this weekend that he’s never sent an email. Not once.

We should be worried that the officials charged with setting policy about how we track and archive digital communications don’t actually use email themselves. What about messaging services? What about Slack? How can our elected officials on either side of the aisle possibly have a meaningful dialogue about how our government preserves its history digitally when they’re still using typewriters?

In reality, there is no practical way to monitor and archive every digital conversation—just as there is no way to control or monitor the thousands of daily conversations that happen over coffee or during walks between federal buildings. Legally, emails may have to be saved and archived—but there’s no provision dictating what to do about in-person conversations.

The government has two choices. It could build and maintain its own internal network capable of massive data collection, tagging, and sorting. The network would need to be used exclusively for all communications and by all staff—from special advisers to temporary budget consultants to contractors overseas. Beyond archiving emails, it would need to track all text messages, conversations from chat clients, and anything else that might emerge in the future, like messages sent over wearable devices. It would also need to somehow archive any incoming messages from constituents, special interest groups, foreign governments, and the like.

Here’s the other, more practical choice: The kinds of conversations we’d want to review and archive—the juicy stuff—are happening in real life, far away from email. An updated law is necessary, but it ought to be written by people who understand the realities of modern communication. And who know that anything too broad won’t be meaningful, too narrow won’t be enforceable, and too restrictive will just lead us back to the same debate a few years from now.