The British satire Yes, Minister once captured the politician’s reaction to any crisis with this syllogism: “We must do something. This is something! Therefore we must do it.” In the case of the Paris terror attacks, American politicians have grabbed at two somethings: refusing to accept Syrian refugees, and demanding encryption backdoors so that intelligence agencies can better spy on people. And as one would expect from any instant-reflex policy proposal, neither will do a thing to prevent terror attacks. And in the case of encryption, at least, the politicians and intelligence leaders are too technologically ignorant to even understand what they’re asking for.

The demand for encryption backdoors, which would grant law enforcement agencies their own “keys” to decode private and strongly encrypted communications, is not new, but it’s been steadily gaining volume, with a loud uptick every time a high-profile hack, like Sony Pictures or the federal Office of Personnel Management, occurs. It’s true that ISIS has displayed increasing technological sophistication. But as the Intercept reports, the Paris terrorists appear to have done at least some coordination over unencrypted SMS, which would mean encryption-cracking wouldn’t have even been needed to snatch those communications and stop the attacks, contrary to what New York City Police Commissioner William Bratton insisted on Sunday. (And as Marcy Wheeler wrote in Slate on Monday, metadata surveillance didn’t help either.) Moreover, given that the National Security Agency and the U.K.’s Government Communications Headquarters already sweep up unencrypted data with a vacuum-cleaner approach, it wouldn’t be surprising if one of these agencies actually did capture the terrorists’ communications, only to ignore them. They have more data than they can process. So what, then, is the reasoning behind wanting to crack encryption?

In order for agencies like the NSA to get these backdoors, we have to assume they’d require private keys into networks that would be kept in escrow but could be obtained legally whenever the government decided. This would immediately put the security of any encrypted communication at risk should those private keys be compromised by another Edward Snowden or worse. A theoretical alternative, termed “split-key encryption,” is so technologically infeasible even the FBI admits it’s not going to happen. FBI General Counsel James Baker said just this month, “It’s tempting to try to engage in magical thinking and hope that the amazing technology sector we have in the United States can come up with some solution, and maybe that’s just a bridge too far. Maybe [split-key encryption] is scientifically and mathematically not possible.”

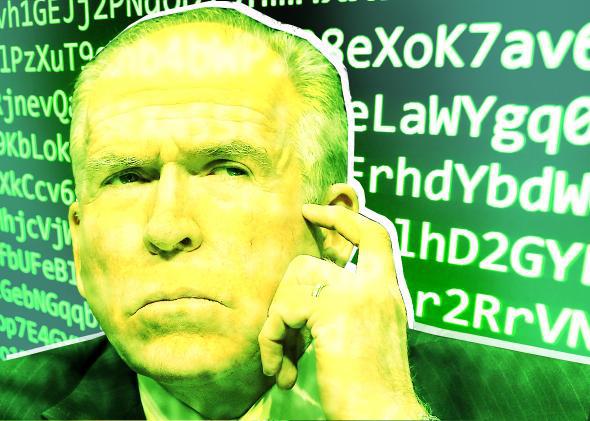

CIA Director John Brennan, whose personal AOL email account was hacked by teenagers last month, lacks Baker’s technical acumen. As Wired’s Kim Zetter reported, Brennan had sent sensitive government documents to his personal email from his work email and had evidently done so without any encryption whatsoever. If Brennan is so lax with his own security, we should worry about securing our own data from attack rather than making it less secure in the name of expanded spying capabilities. Don’t we need a CIA director who knows how to prevent his own communications from being hacked by teens? For all the attention paid to Hillary Clinton’s private email accounts, Brennan seems to have earned immunity from such obvious questions. Brennan is a locksmith who leaves his own doors open.

Yet Brennan is Alan Turing next to Sens. Dianne Feinstein and John McCain, who this week invoked fear, uncertainty, and doubt as though it were Sept. 12, 2001. Said Feinstein: “If you create a product that allows evil monsters to communicate in this way, to behead children, to strike innocents, whether it’s at a game in a stadium, in a small restaurant in Paris, take down an airliner, that’s a big problem.” (If only gun manufacturers faced the same level of hyperbole as security engineers.) Calling for legislation that would mandate backdoors, McCain echoed Brennan’s demands, saying, “It’s time we had another key that would be kept safe and only revealed by means of a court order.” McCain didn’t explain what he meant by “kept safe” and “revealed,” even though neither term is trivial when it comes to encryption keys. Nor did he seem to realize that you simply can’t mandate that all encryption algorithms automatically give backdoor keys to the government. Trying to stop people from using encryption without backdoors would be like trying to stop people from pirating music and movies, and we all know how successful that effort has been. To paraphrase an argument made about a certain other unregulated technology: If secure encryption is outlawed, only outlaws will have secure encryption.

Anti-terrorism ought to demand that we secure our own sensitive digital assets through encryption and that law enforcement do the targeted human policing that time and again has proved far more effective at foiling terror plots than indiscriminate and ineffective surveillance. Remember, the NSA’s bulk collection program foiled exactly zero terror plots, by its own admission. The call for encryption backdoors is just another extension of this futile and counterproductive dragnet. The persistent idée fixe around encryption’s potential dangers and the supposed silver bullet of backdoors pales next to the real holes remaining in our own security, which allowed the compromising of 20 million personnel files in the OPM hack and the sheer destruction of Sony Pictures’ internal systems by cyberterrorists. Introducing encryption backdoors will carve one more gaping hole in our Swiss-cheese virtual infrastructure. Politicians’ and intelligence leaders’ combination of technological illiteracy and ham-fisted power-grabbing matches every stereotype of uneducated and ineffectual American brute force. While decorum and good sense would seem to demand that such policy discussions be treated with high seriousness and respect to all involved, the level of ignorance displayed by politicians and intelligence leaders on these issues is simply galling. To be blunt, the technologically savvy view Brennan, Feinstein, and McCain with contempt thanks to statements like the ones they made this week. Their advocacy for encryption backdoors should be taken about as seriously as the latest ideas of Donald Trump.