Every scandal needs a face, but the parade of drab German middle managers in the Volkswagen emissions-testing scandal has yet to produce the right one. It’s not Martin Winterkorn, who resigned as the company’s CEO last week after it was revealed that Volkswagen had installed “defeat devices” on more than 11 million diesel cars since 2009, causing them to “cheat” on emissions testing, producing acceptable admissions when tested before revving up to more than 40 times over that limit in real usage. With such a cartoonishly outrageous mission, the cheating device itself is more colorful and malevolent than any of the purported wrongdoers we’ve seen so far.

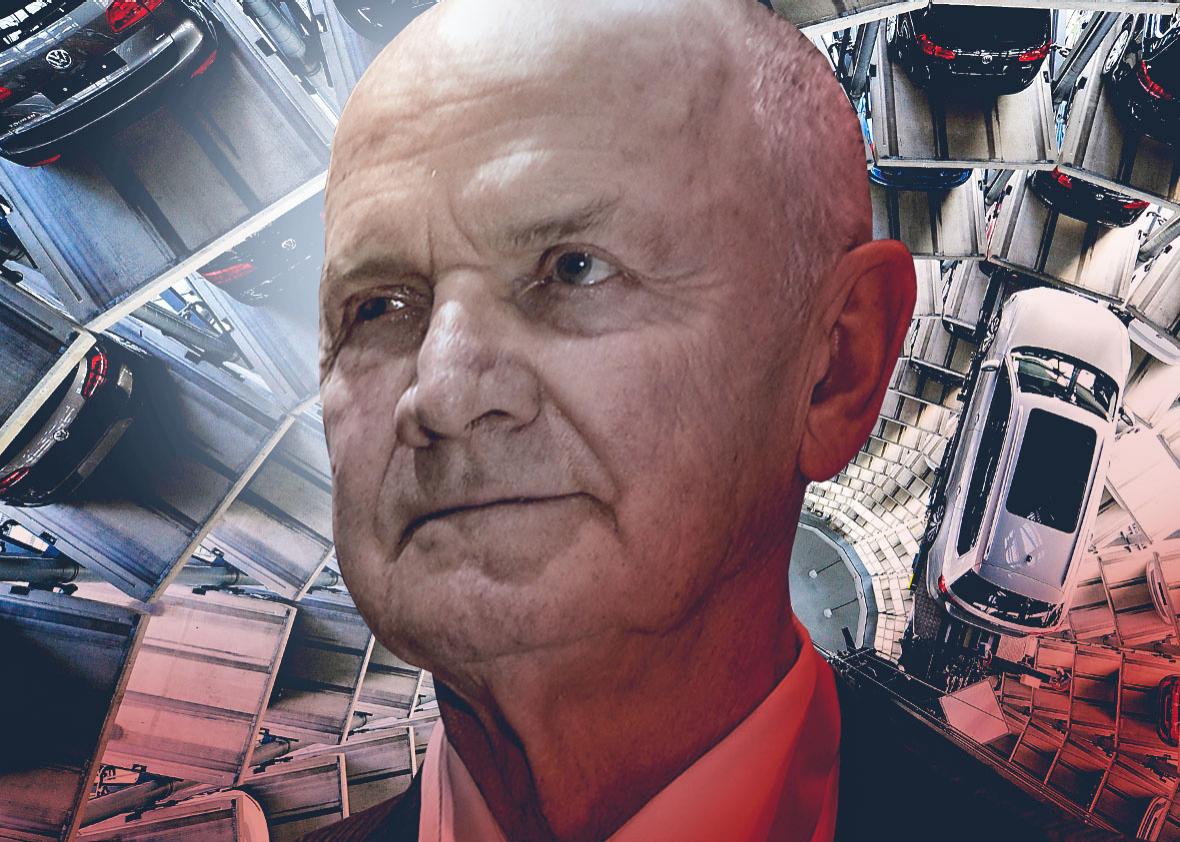

But if the scandal has its villainous mastermind, someone who was powerful and involved enough to be responsible—indirectly, at least—it is most likely Ferdinand Piech, the grandson of Ferdinand Porsche and a powerful member of the Porsche clan that controls Porsche and VW. Until this spring, Piech chaired the Volkswagen Group’s board, and several of his hand-selected executives are at the heart of the affair. And yet almost no one in the English-language press is talking about him or the opaque, dynastic ownership structure of VW, which allows for almost no outside shareholder input. As with Chris Christie and Bridgegate, Piech may have plausible deniability when it comes to the defeat devices, yet he presided over the culture that allowed them to be installed. With his reputation for tightly controlling Volkswagen’s operations and carefully shaping its executive ranks, Piech owns the company’s successes over the last 20 years. He ought to own this scandal too.

The first public face of the scandal wasn’t Piech, but Winterkorn. The company’s CEO resigned on Sept. 23, five days after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency accused VW of cheating on 500,000 Volkswagen and Audi vehicles, a number that quickly ballooned to 11 million as Volkswagen fessed up. The EPA didn’t nail the exact culprit on its own; the independent International Council on Clean Transportation conducted independent on-road tests in 2013 that revealed the huge emissions discrepancies, and only then did the EPA act. At first VW stonewalled regulators, but the evidence was undeniable, even if unbelievable. The company had programmed its diesel engines specifically to detect situations in which they were being tested. This is an audacious, outrageous, and very intentional feat. Indeed, such coordinated large-scale fraud, across multiple divisions (VW, Audi, Skoda, and others), required significant participation from engineers and management both. In a written statement, Winterkorn said: “Above all, I am stunned that misconduct on such a scale was possible in the Volkswagen Group. I am doing this in the interests of the company even though I am not aware of any wrongdoing on my part.” Yet Winterkorn doesn’t claim he was unaware of wrongdoing in the statement. That doesn’t seem like an accidental omission.

Winterkorn rose to VW’s top position in 2006, having been a longtime protégé of Piech, who had fired Winterkorn’s predecessor Bernd Pischetsrieder. At the time, the New York Times quoted analyst Arndt Ellinghorst on the change: “Pischetsrieder was trying to push through decisions that Piech was resisting. Winterkorn is someone who will always do everything that Piech says.”

Three years later, VW started installing defeat devices.

Last week, anonymous sources told Bloomberg that two VW research and development executives would be dismissed. On Sept. 28, those two—Audi development head Ulrich Hackenberg and Porsche development head Wolfgang Hatz—as well as VW development head Heinz-Jakob Neusser were suspended without pay rather than fired. Like Winterkorn, all three are longtime VW employees, and according to Car and Driver, “All three of them had been hand-picked by Ferdinand Piech.” Piech’s background is in engineering, having designed the Porsche 917 and the 5-cylinder Audi engine, and he took an avid interest in projects like the $1.4M, 250 mph Bugatti Veyron and the luxury Phaeton, both of which have been termed “Piech’s folly.” Even if Piech didn’t know about the scandal, his draconian management style, close selection of executives, and shuttering of dissent clearly enabled the conditions that allowed for such gross malfeasance. If VW executives greenlit the defeat devices without Piech’s knowledge, they may well have done so to stay in his favor.

In one of the best pieces written on the scandal, the Times’ James B. Stewart discussed the sclerotic and incestuous boardroom culture of Volkswagen: “Porsche and Piech family members own over half the voting shares and vote them as a bloc under a family agreement.” The history of the German-Austrian Porsche-Piech dynasty and their auto companies, Stewart points out, has always been unusual: “The company [VW], founded by the Nazis before World War II, is governed through an unusual hybrid of family control, government ownership and labor influence.” Stewart’s piece is necessary reading in full, explaining the high drama that gives rise to ledes like this one from Automotive News: “Former Volkswagen Chairman Ferdinand Piech is challenging VW’s choice of two of his nieces to replace him and his wife as supervisory board members.” It’s closer to Gosford Park than Margin Call—talent matters less than bloodline. This sort of environment—remote, insular, and unchecked—would explain why a company might have the audacity (and lack of sense) to try to cheat the emissions testers. According to Bloomberg, VW workers in America lacked the expertise to create the defeat device; all the skullduggery was at VW and Audi headquarters in Germany, inside Piech’s centralized, remote fiefdom. It is exactly the sort of environment that will shut out dissenting views and foster groupthink on the most ridiculous of ideas—like programming engines to cheat on emissions tests.

Though the 78-year-old Piech officially retired in April after a power struggle within his own family, he doesn’t appear to have relinquished power readily. Piech allegedly sabotaged Winterkorn’s bid to replace him as supervisory board chairman, choosing VW chief financial officer Hans Dieter Poetsch instead. Piech, whose rule over VW is rarely described without the expression “iron hand,” was driven by a desire to surpass his grandfather. The Financial Times quoted him on his priorities: “VW, family, money.” The FT piece describes him as “bulletproof,” surviving multiple coup attempts, and brooking no tolerance for dissent or weakness. It gets into some personal gossip about him as well, which is a lot less interesting than the fact that his father Anton Piech and grandfather Ferdinand Porsche were members of the Nazi SS who used concentration camp slave labor to build cars and rockets. Ferdinand Piech himself hasn’t been forthcoming about his ancestors’ acts, attacking German historian Hans Mommsen when Mommsen wrote a book chronicling VW’s wartime activities, Volkswagen and Its Workers During the Third Reich, published in 1996—a book commissioned by Piech’s predecessor as board chair, Carl Hahn. Calling Piech’s father and grandfather “morally indifferent,” Mommsen wrote that in 1943, “Anton Piech bluntly declared that he had to use cheap Eastern workers in order to fulfill the Fuhrer’s wish that the Volkswagen be produced for 990 Reichsmark.” According to Phil Patton’s history of the VW Beetle, Piech responded by denying Mommsen a promised translation of the book into English (it remains untranslated). Mommsen’s assessment of Piech: “He is the kind of man who sees conspiracies.” Patton himself has said that Piech restored VW’s denial of its shameful history. Compared to that, installing some ill-intentioned hardware might seem like nothing.

It is possible—although not likely in my eyes—that Piech had no idea what was going on and that his three handpicked R&D executives all went rogue on him. But executives from Jay Gould to Roger Smith to Jeff Bezos control the cultures of their companies and set priorities, and for all the attention granted Winterkorn, he was clearly a longtime proxy for Piech until he fell from favor. Any investigation that does not seriously question Piech’s role in and knowledge of the scandal will have stopped short of questioning the true reins of power at VW. Much of the intrigue and chair shuffling already seems to be designed to protect Piëch and his clan and their tight hold on the reins of VW. Hermes EOS director Hans-Christoph Hirt has already criticized the board’s choice of “corporate insiders as CEO and chair-elect” as little more than cosmetic changes. Will European governments be willing to challenge such a powerful family regime? True reform would require not just prosecuting VW executives and board members with knowledge of the fraud, but also breaking up the unaccountable corporate structure based in the dubious maneuverings of a fantastically wealthy and privileged family. Reforming VW won’t take corporate reform; it will require a dynastic downfall.

This article is part of Future Tense, a collaboration among Arizona State University, New America, and Slate. Future Tense explores the ways emerging technologies affect society, policy, and culture. To read more, visit the Future Tense blog and the Future Tense home page. You can also follow us on Twitter.