The Sony Pictures hack—whodunit? Everyone is certain it was either North Korea or not North Korea. Even as the United States imposes new sanctions on North Korea for allegedly hacking Sony Pictures, stealing 100 terabytes of data, and obliterating the movie studio’s internal systems (as I discussed in a previous piece), there remain serious questions as to who exactly was responsible.

On Wednesday, FBI Director James Comey, defending the government’s attribution of the hack to North Korea, revealed that some of the emails from hacker group the Guardians of Peace came from IP addresses “exclusively” used by North Korea. As with previous FBI reports, it was vague talk, and we have only Comey’s word for it. But the many writers raising questions about North Korea’s involvement aren’t making things much clearer. For every cautiously skeptical article like Rem Rieder’s “Maybe North Korea wasn’t behind Sony hack” in USA Today or Kim Zetter’s Wired piece arguing that “Attribution Is Difficult if Not Impossible,” there are a dozen tendentious and factually sketchy pieces that point a finger in one direction or another. Even an apparently telling clue like the fast speeds at which Sony’s data was downloaded, which some thought might point to an inside job, has turned out to be wholly inconclusive. If you think you know who did it and you aren’t a member of the Guardians of Peace, it’s likely that you’re wrong. Because the question isn’t just whodunit, but how many dunit.

In a widely shared piece for the Daily Beast last month, security researcher Marc Rogers flatly declared that North Korea wasn’t behind the hack, writing that the supposed IP addresses cited by the FBI—the one seemingly concrete piece of evidence given in its rather vague justification for blaming North Korea—are actually public proxies scattered throughout the world. That’s true, but the FBI never said otherwise. What the FBI said was that it observed that North Korean IP addresses communicated with those public proxies. Unlike Rogers, I don’t think the FBI’s unrevealed evidence is limited to the recorded histories of those public IP addresses as anonymous proxies for hacker activity; rather, I suspect it’s surveillance traces of Internet pipes. Since we know that the National Security Agency has hacked into intercontinental pipes with its MUSCULAR program to spy on Google and Yahoo traffic, I can imagine that the FBI might be seeing something occur between those proxies and known North Korean infrastructure. Now, I’m not necessarily willing to trust the FBI’s secret evidence without knowing more. But by making a thin Occam’s razor case for an inside job by “a disgruntled Sony employee,” Rogers weakens the very valid point that we should be quite sure before we accuse North Korea of cyberterrorism. For my part, I remain unconvinced by both Rogers and the FBI. And I certainly don’t trust a heavily cited analysis of the hackers’ linguistic choices that many skeptics have pointed to as evidence that North Korea couldn’t have been responsible.

Rogers thinks that the hackers, being Sony insiders, were native English speakers. That claim was contradicted by cybersecurity consultants Taia Global’s linguistic analysis, which claims that based on the nature of the bad grammar of the messages (e.g., “We will clearly show it to you at the very time and places ‘The Interview’ be shown, including the premiere, how bitter fate those who seek fun in terror should be doomed to.”), the hackers were most likely native speakers of Russian, not Korean. This study has been cited everywhere from Reuters to Boing Boing, but no one has examined it to see if it’s convincing. It’s not, for several reasons.

First, the sample size is extremely small; between the various emails and text files, we simply don’t have much text from the hackers. The study itself says that if there were multiple authors of the messages (quite likely given that some messages are much more grammatically accurate than others), it assumes they all spoke the same language: “Such an assumption is necessary to do any analysis of the linguistic style of the messages, due to the small amount of data available.” Not reassuring.

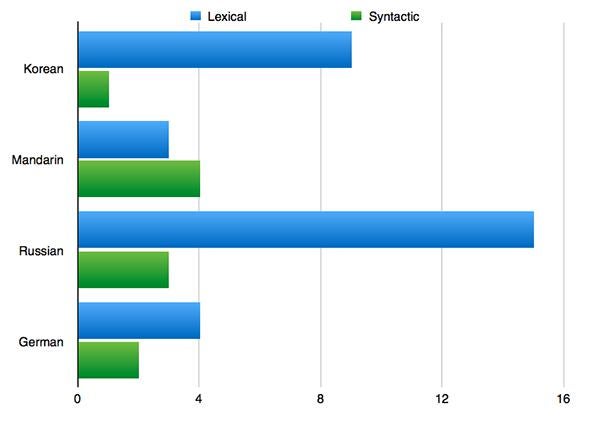

Second, the analysis itself does not overwhelmingly point at Russian speakers. In their chart of the lexical and syntactic errors, even though Russian wins with 15 lexical error similarities, Korean comes in at a respectable No. 2 with nine.

Taia Global

Third, the analysis is incomplete. It only looks at lexical and syntactic errors, and not curious word choices like the use of excite in “The data to be released next week will excite you more.” And while the grammatical analysis takes into account omitted and superfluous articles (as in “All the world will denounce the SONY”), it does not count the places where there was a lack of such errors, or analyze what such accuracy could mean. Neither does Taia consider errors like “It’s your false” or “We have already given much time for you.” So based on a selective analysis of a selected number of errors, the study makes only a tentative conclusion that Russian might be more likely than Korean. The jump from the tentative “likelihood” of the text of the analysis to the claim of “establishing nationality” in the report title suggests that the report was irresponsibly rushed and exaggerated.

Fourth, and most seriously, some of the messages may not have come from the hackers. An email sent to Sony employees demanding they beg for clemency (“Please sign your name to object the false of the company”) was disowned a couple of days later in a more convincing post on the GitHub code repository (“We know nothing about the threatening email received by Sony staffers”), a discrepancy the study ignores. Another unauthenticated message comes from a Dec. 20 text file posted on pastebin.com that links to a “You are an idiot” video, which seems awfully hard to square with the hackers’ threat to blow up movie theaters a week earlier. I will be bold enough to say that I believe this message was not the work of cyberterrorists.

The near-certainty that at least some of the purported Guardians of Peace messages are fake introduces a huge amount of noise into the analysis. What if instead of assuming the messages are predominantly authentic, we are skeptical of every message? Looking through RiskBasedSecurity’s thorough breakdown of the chain of events and leaks—easily the best I have found—we discover that the real hackers might not have cared about The Interview at all, because their initial demands were entirely different.

Mashable reported that on Nov. 21, three days before the hack, Sony executives received an email from “God’sApstls,” a name that subsequently appeared in the hack malware. The text of the message demands money and says nothing about The Interview.

We’ve got great damage by Sony Pictures.

The compensation for it, monetary compensation we want.

Pay the damage, or Sony Pictures will be bombarded as a whole.

You know us very well. We never wait long.

You’d better behave wisely.

From God’sApstls

The onscreen message accompanying the hack on Nov. 24 only says, “We continue till our request be met,” without specifying what that request is.

According to Deadline, it was only on Nov. 28 that Sony itself speculated that North Korea might be responsible, while Re/code reports that Sony was set to blame North Korea on Dec. 3. That was also asserted in an Verge article on Dec. 1, “New evidence points to North Korean involvement in Sony Pictures hack,” based on an email of dubious provenance with better grammar than previous missives. (The Verge claims it came from an account associated with the hackers, but such things can be faked.) “Our aim is not at the film The Interview as Sony Pictures suggests,” it says. It is not until Dec. 8 that the demand to stop showing The Interview emerges on GitHub, by which point talk of North Korea’s involvement had already reached high pitch thanks to Sony and the press.

After several more leaks that conspicuously did not mention The Interview, Dec. 16 brought the terrorist threat against theaters showing the movie with the chilling statement “Remember the 11th of September 2001.” That was in a pastebin text file that also contained links to torrents of leaked data.

Of the communications that had to be from the hackers (Nov. 21, Nov. 24) and the subsequent dozen or so that were accompanied by new leaks (as far as I can gather) in the message text, only those from Dec. 8 and 16 mention The Interview, long after far more dubious messages had put the North Korea theory into circulation. Yet even those particular messages are atypical. RiskBasedSecurity writes on Dec. 8, “There is speculation that the new announcement may not be authentic as it did not get sent out via the previous channels, and suggests an almost afterthought of blaming the movie for their actions.” As for the Dec. 16 leak, it was accompanied by an uncharacteristically small leak: Sony Pictures Chairman Michael Lynton’s Outlook mailbox files. “It should be noted that these spools are almost half the size of previous leaked email spools, and neither file contains a ‘Sent’ folder,” writes RiskBasedSecurity. Given the comprehensive nature of the hack and previous leaks, the incomplete nature of that particular leak is highly unusual. Could Lynton’s mailbox have been obtained outside of the hack—or even by someone else—and utilized to make the theater threat as a prank by someone other than the original hackers? Perhaps not, but it’s a possibility that I hope investigators will take the time to rule out.

We can be pretty certain that all of the messages were not from the Sony hackers, but the provenance of the two that refer to The Interview is the most important, because if those aren’t real, a lot of December’s events start looking pretty silly. The sheer lack of authenticated text relating to The Interview—and the far larger number of hacker missives that don’t mention it—gives the greatest cause for skepticism about the film being the hackers’ motive. It would also point away from The Interview having had anything to do with the actual hack. Comey says that some of the emails came from North Korean IP addresses. Assuming that’s true, the question becomes: Which ones? Could North Korea itself have jumped on the bandwagon after the hack?

At the least, Sony was incredibly irresponsible in loudly floating the North Korea theory well over a week before the government bought into it, and the press was irresponsible in not questioning it more at the time. I bemoaned the poor quality of the reporting on Gamergate last year, but that was just video games. This is a high-stakes national security story that has already resulted in increased global tensions, and the speed at which even respectable outlets are running with questionable or empty claims is all too reminiscent of the post-9/11 frenzy to find evidence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. We should recognize how little we know about the culprits, and beyond that, our ignorance as to how many culprits there are.