The best video game I played last year is a science-fiction thriller about alchemy, and it has no graphics or sound effects. With little more than text, it manages to be far more impressive and innovative than the last Metal Gear Solid game.

Hadean Lands is a text adventure, a genre also known by the fancier name “interactive fiction.” Software company Infocom popularized the form in the 1980s with floppy-disk games like Zork and Trinity. But Hadean Lands, written by longtime interactive-fiction stalwart Andrew Plotkin, isn’t merely an excellent, challenging, and creative game. It is an unabashedly modernist and self-referential game, one that builds on the past achievements of its genre and pushes at its boundaries, much like how modernist authors from James Joyce to Rebecca West advanced their literary traditions. Hadean Lands is a milestone. No, it’s not Joyce—Plotkin doesn’t quite have the writing chops—but I did enjoy it more than T. S. Eliot.

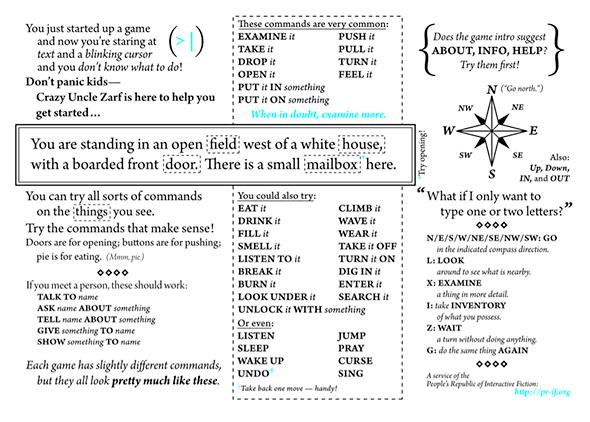

Text-based games have their roots in Zork, developed in the late 1970s at MIT and released by Infocom in 1980. Zork laid out the basic interface for the genre, which has remained more or less unchanged ever since: descriptive, usually second-person narration that responds to a player’s typed imperative commands (in bold).

West of House

You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door.

There is a small mailbox here.

What would you like to do next?

>open the mailbox

Opening the small mailbox reveals a leaflet.

During its heyday, interactive fiction hit creative peaks with Infocom titles like A Mind Forever Voyaging (in which you play an AI navigating a future world with Tea Party–esque rulers) and Trinity (a chilling atomic-bomb fantasia). By the end of the 1980s, though, the genre was no longer commercially viable, effectively ending Infocom as well as the British company Magnetic Scrolls (one of the few games companies headed by a woman, Anita Sinclair). But people who had been raised on the games gave text adventures a second life in the mid-1990s, thanks in large part to the immense efforts of British mathematician and poet Graham Nelson, who reverse-engineered Infocom’s game format and wrote a new language, Inform, specifically tailored to produce interactive fiction games. (Michael J. Roberts’ TADS, which preceded Inform, also deserves mention.) A vibrant community of enthusiasts started writing new games, playing them, and, significantly, discussing them on Usenet, creating a tight-knit fanbase that brought the form to new peaks. The annual Interactive Fiction Competition provided a forum for newcomers and boosted names like Adam Cadre, Emily Short, and Plotkin into the upper echelon of the form.

In recent years, though, the competition hasn’t produced as many striking or original titles, and the integration of multimedia elements and self-consciously “literary” ambitions have failed to bring much new excitement to the genre. Hadean Lands rejuvenates the form’s essence for the first time in many years, and points the way to new and more mind-twisting possibilities for interactive fiction.

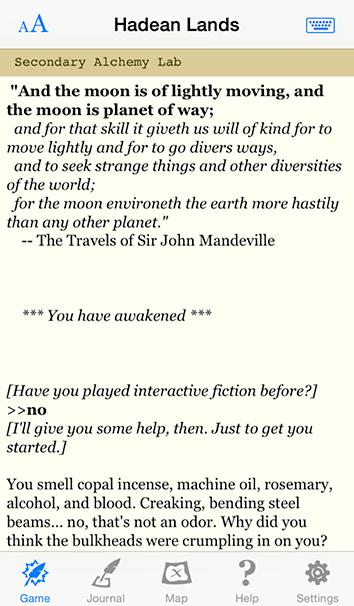

In Hadean Lands, which is available on iOS, MacOS, Windows, and Linux, you play a lowly Ensign, the only surviving crewmember of a spaceship that has crashed on a very foreign planet. But this isn’t any future we could have, because in the game’s universe, alchemy is real, having been refined into a rigorous science in which metals and other objects can be transformed and imbued through smells, sounds, totems, and words, based around the four principles of Earth, Air, Fire, and Water. (Since alchemy is science, the game’s alchemy is a syncretic assemblage of independent traditions from Europe, pre-Columbian America, India, China, and elsewhere, though the voodoo loas of Plotkin’s earlier System’s Twilight aren’t directly in evidence.)

Here, for example, is the (slightly abbreviated) ritual for “brass tarnish cleansing,” which isn’t too tricky beyond the spelling of “phlogistical” (player commands are in bold):

>recall the brass tarnish ritual

“FOR THE CLEANSING OF BRASS TARNISH: Prepare an atmosphere of fiery principles. Place a brass token within the bound, and seal it. Speak a word of essential nature, so that the properties of brass may be evoked. Compound the atmosphere with a resinous note. Then intone the Lesser Phlogistical Saturation to complete the token’s investment. Place token directly on tarnished item.”

>put the brass pin in the bound

You put the brass pin into the workbench bound.

>say the sealing word

You take a breath, trace the bound in your mind, and intone the simple sealing word. The arc begins to glow orange around the brass pin.

>say the lesser phlogistical saturation

You begin the Lesser Phlogistical Saturation. The sounds try to bend and smear on your lips, but you are on your guard, and you hold clearly to the formula.

The energy slowly converges. The orange light flares, drawing together the blended aromas and the words that you speak.

When the light fades, a symbol shines on the surface of the brass pin.

The rituals get considerably more complicated and impressive as the game goes on—the “Dragon Invocation” is a lot more titanic than making a magic cleaning pin.

As with many what-the-hell-happened games, in Hadean Lands you explore the spaceship to find out what caused the crash, who is responsible (a number of crewmembers appear to have been involved in shady dealings and love affairs), and how to get the ship working again. As you execute the standard maneuvers of collecting items, opening locked doors, and finding clues—very much the traditional stuff of exploration-based interactive fiction (IF)—the game throws a number of revelatory formal twists your way. I’ll reveal only the first, which is that shortly into the game, your character will die—and come back to life, with the entire game reset to its initial state. But not quite, because, as in Groundhog Day, you retain the knowledge of what happened on previous runs—specifically, alchemical formulas.

Image courtesy Andrew Plotkin

This turns out to be hugely significant, since once you learn a formula, you don’t have to go back and find it again on subsequent runs. Let’s say you find a lock-pick that can open a single door, after which it breaks. You are then faced with two doors. Behind the left door is the very important alchemical formula that turns water into wine. Behind the right are hordes of riches. What to do? Open the left door, breaking the lock-pick; read and memorize the formula; then off yourself (“KILL ME” works) and use the once-again pristine lock-pick to open the right door. Wine and riches are yours.

Image courtesy Andrew Plotkin

This sort of metatextual maneuver has popped up in other games, most famously Braid, which took a Super Mario Bros.–type platformer but gave you the ability to manipulate time, making for a number of ingenious puzzles. Some other text adventures have also played with Groundhog Day–like mechanics, like Adam Cadre’s Endless, Nameless and J. D. Clemens’ Möbius. Plotkin’s earlier Spider and Web, which has been voted the greatest text adventure of all time by the community of the Interactive Fiction Database, works its own brilliant twist on a story being repeatedly told and retold—in that case, with you playing a spy under harsh interrogation. But Hadean Lands’ formal achievement is more profound, because rather than just mucking with the mechanics, it abstracts away an entire level of gaming—the standard puzzle-solving text adventure—into a higher-order metagame about what seemed to be the initial game. Once you’ve solved a puzzle, the game performs the solution for you on subsequent runs. Hadean Lands becomes less about solving puzzles than figuring out which puzzles need to be (automatically) solved in the right order.

That, in particular, is what makes Hadean Lands a modernist game. (If you think it sounds postmodernist, that’s only because modernists actually invented most of the stuff that’s called “postmodernism,” while postmodernism invented making a Really Big Deal out of it.) Text adventures are, in a sense, unique among game forms. Despite their origins in the 1980s, the games and the format have held up a lot better than anything from that era that used graphics. This owes to the fact that when it comes to branching logic, puzzles, and plot machinations, games have barely progressed in the last 30 years, certainly when compared to the exponential increases in graphics. Even most self-declared “experimental” or “indie” games just layer a patina of pretentious art wank (the sadistic Gods Will Be Watching merits special mention here) on top of the same primitive mechanics that have been with us for decades. The leap Hadean Lands makes in its gameplay mirrors the multilevel organization of hardware and software (Plotkin’s background is in computer science)—from silicon logic gates up through assembly language on up to higher-level programming languages. Each level abstracts away the last into a simpler and more powerful toolset. Programmers will find Hadean Lands quite amenable to their way of thinking.

Plotkin funded the game through Kickstarter, ultimately raising $30,000, and the amount of effort he put into it is staggering. The dependency pathing—by which the game figures out the smallest set of actions to take to achieve the player’s chosen goal—must have been a nightmare to code, and as a technical achievement it could be the most complicated text adventure ever written. Hadean Lands received next to no major press, a disgrace given Plotkin’s large standing in the interactive-fiction world. Alongside the even more dispiriting cancellation of IF leading light Emily Short’s game Blood and Laurels by Linden Labs last year, such lack of recognition brings to mind William H. Gass’ words that “Serious writing must nowadays be written for the sake of the art.” On the other hand, that such an achievement could be funded and produced for $30,000 suggests that there’s still room for real art in the gaming world. You just have to look to the margins.