Today, we live in a world of data. Twenty years ago, we didn’t. Just as computing power has exponentially increased over the last 50 years, doubling every two years or so, the amount of computational data has been doubling at a similar rate. Ninety percent of all the data in human history was created in the last two years. And the advent of “big data” brings with it such scary and Orwellian doings as Facebook conducting mood experiments on its users.

OkCupid founder Christian Rudder jumped to Facebook’s defense on Monday, talking about how the online dating service had conducted similar experiments on its millions of users, including lying to them about how well-matched they were with potential dates. (People weren’t quite as outraged as they were with Facebook, possibly because, in the words of Gawker’s Jay Hathaway, “Online dating already feels like consenting to participate in a social experiment.”)

So however bad Facebook’s experiment was, it looks like there might be a lot more of it in our future. But unlike Facebook, which published its findings in a humorless academic paper, OkCupid treated its results with some serious skepticism, raising the question: What is big data actually good for? Does it even work?

Not all data is equal, of course. The complete works of Isaac Newton and William Shakespeare take up about as much space as a sound file of Pharrell’s “Happy.” But even if you restrict yourself to words and numbers, the great works of human civilization have now been drowned in measurements, statistics, and status updates. Songs and texts are on the order of megabytes. There are a bit more than a million megabytes in a terabyte, which is about what it would take to store the entire printed material of the Library of Congress. The total human store of information is a few billion Libraries of Congress, measured in zettabytes (a billion terabytes).

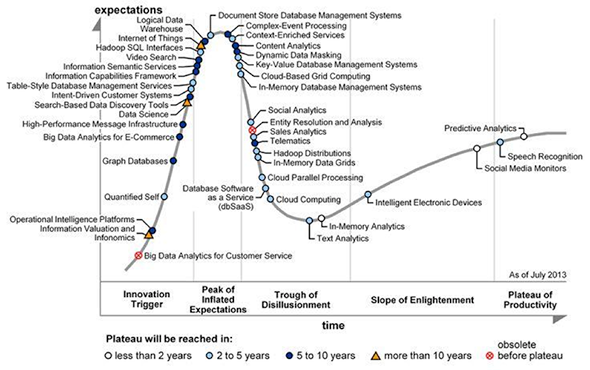

What do we do with all our big data? The answer is often “not much.” The National Security Agency stuffs all its surveillance data into its Utah data center despite not having the tools to analyze most of it. Data storage costs have become so cheap that it’s far easier to collect petabytes than to figure out why they’re useful. Last year, market research firm Gartner put big data and many of its technologies near the top of the “peak of inflated expectations” of its hype cycle, to be followed soon by a “trough of disillusionment.”

Courtesy of Gartner

Why the trough? Because big data has yet to yield big money. For all the hype about the quantified self, the Internet of things, and data science, big data has yet to yield a true killer app. Google Flu Trends is a fascinating idea, but extrapolating flu incidents from Google searches on flu keywords has not produced reliable results. The New York Times recently published a piece by Sendhil Mullainathan wondering if search queries for “slow iPhone” might imply that Apple is intentionally slowing down older iPhones as new ones are released, but he concluded merely that big data doesn’t tell us enough to know for sure.

Big data really only has one unalloyed success on its track record, and it’s an old one: Google, specifically its Web search. (Disclosure: I used to work at Google, and my wife still does.) Way back in the last century, Google found that by analyzing the entirety of the Web, a sufficient number of pages gave them the ability to obtain a) really good results for keyword searches and b) high click-through ads for those keywords. What’s more, it didn’t require any particularly sophisticated analysis of their data. Simply examining word frequencies and the link structure of the Web was enough to obtain high-quality analysis. (This has changed as SEOs and click farms have tried to game the system, but the point stands.) As artificial intelligence kingpin Peter Norvig puts it, “Simple models and a lot of data trump more elaborate models based on less data.”

Many companies, including Google itself, have tried to repeat that success since then, but no one has really succeeded. Amazon is probably the No. 2 big data success because of its recommendation engine, but Amazon’s success was still not primarily dependent on big data–style analysis in the way that Google’s core business has been. Facebook has succeeded more through viral ubiquity than through big data innovation.

The recent Facebook data science experiment is telling. Regardless of moral outrage, the problem with Facebook’s recent attempt to make its users feel bad (or good) by curating their news feeds is that the manipulation was inept—because the analysis was done using the inadequate Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count software. For example, “I don’t feel happy” and “I feel happy” both registered as “positive” updates, simply due to the presence of the word happy.

So problem No. 1 is that big data is frequently bad data. For a closer look at big data’s pitfalls, there’s no better example than OkCupid, which has been both honest and irreverent about its own use of data. OkCupid was an early proponent of the “quantified self” big data paradigm, asking you to answer multiple-choice questions (and ask some of your own) in order to find your “match percentage”—your compatibility, more or less—with other users. The questions can be about anything: love, sex, work, politics, hobbies, arithmetic.

Because OkCupid’s Christian Rudder is a sensible guy, he disclaims anything but entertainment value from the stats he publishes. “OkCupid doesn’t really know what it’s doing,” he wrote Monday in a blog post on his OkTrends blog, setting himself apart from the pseudoscience Facebook peddled in its academic paper. Rudder offers three examples of OkCupid’s “experiments.” Two of them seem fairly innocuous: hiding all users’ pictures for a day, and selectively hiding some users’ profile text. The third, in which people were shown false match percentages, is far more manipulative, but it still doesn’t smack of “We succeeded in making users less happy!”—which was people’s real problem with the Facebook experiment.

“Once the experiment was concluded,” Rudder notes, “the users were notified of the correct match percentage.” (Part of Rudder’s message seems to be “Look, OkCupid is more honest than Facebook!” With friends like OkCupid, Facebook doesn’t need ethics panels.)

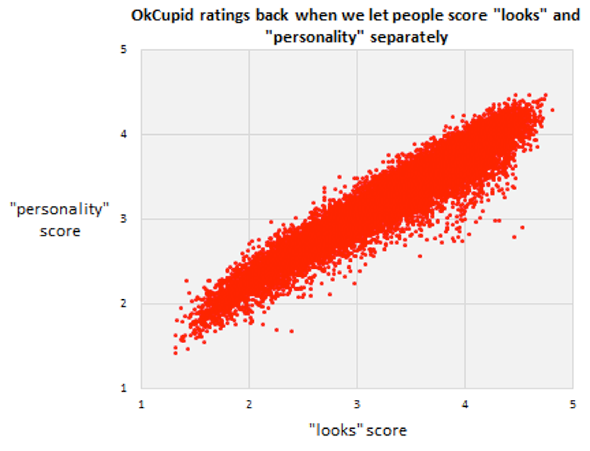

Rudder’s breezy style does obscure some deeper issues. He presents some charts in order to show that looks completely trump personality and profile text, and quips, “So, your picture is worth that fabled thousand words, but your actual words are worth…almost nothing.”

Courtesy of OkCupid

The problem is that Rudder’s data is biased, partly due to the selection bias baked into OkCupid’s model. Not all OkCupid users rate all other OkCupid users; OkCupid controls which people you see (and rate) through its algorithms. It’s not as though people are presented with a random sample of potential matches—they’re being given a prefiltered list of more likely matches. Presented with people with whom you are already more compatible, you tend to let looks trump personality. But OkCupid has presumably filtered out users whose personalities aren’t simpatico with yours.

I have some anecdotal evidence for this conclusion. When a single friend of mine decided to look at his least compatible matches on OkCupid, he found a bunch of white supremacists. (I wish I were kidding.) He never would have come across these people in the normal course of events, since the low match percentage would have kept them safely hidden. So yeah, words may be worth nothing, but only once you’ve weeded out the white supremacists and other nonstarters.

Doing clean experiments under controlled conditions is difficult enough. In the real world, it is often near impossible, which is a fundamental problem with big data. Data is almost always contaminated. Providing rigorous evidence for Rudder’s conclusions would require far more control and experimentation than even Facebook would be able to achieve.

I don’t mean to say that OkCupid’s analytics are little more than the next pseudoscientific development after astrology and Myers-Briggs personality types. Rudder’s conclusions are suggestive (as are Facebook’s), but they don’t meet the bar for scientific rigor, as Rudder himself admits.

Rudder makes a very astute observation at the end of his post, which is that people are more likely to continue conversing with people with whom they have a high match percentage, even if that match percentage is actually false. True or false, data can dictate people’s responses, which can set up a nasty feedback loop in which false data becomes more true. This is one of the biggest sources of big data contamination: It does not work on a closed system. Instead, it puts unproven ideas into the social mediasphere—for example, that certain Google autocomplete results are racist and sexist—and those ideas get bounced around, reiterated, and reflected in the very phenomena big data is measuring. If, say, Facebook decides that users who have written a status update about the “daily grind” are really into grindcore music, or if Amazon accidentally recommends The Road to everyone who buys The Road Less Traveled, it’s easy to imagine that those companies could successfully encourage correlations that don’t exist. That’s why big data’s greatest trick has been convincing the world that it works.