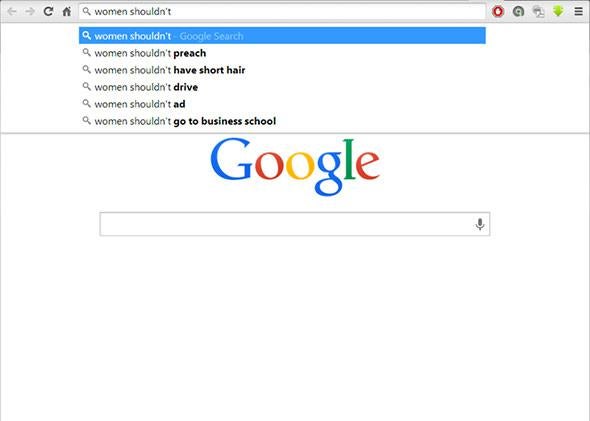

There’s currently a powerful Internet ad campaign by UN Women based around Google’s autocomplete feature. By showing the autocomplete suggestions generated after typing “women shouldn’t,” “women need to,” and so on, the results seem to reveal a ghastly sexism in our collective consciousness. When the top autocomplete suggestion for “women need to” is “women need to be put in their place,” it’s hard to deny that women have it tougher than men, whose top autocomplete suggestion is the comparatively innocuous “men need to feel needed.”

It is a brilliant campaign, one that makes use of the hive-mind nature of Internet discourse to make a case that sexism, latent and otherwise, isn’t a thing of the past. Yet the complicated algorithms of autocomplete—whose results not even Google can predict with full certainty—point out a subtler issue that deserves some thought: Google can easily treat a link or a quote as an endorsement.

Make no mistake, I don’t have a problem with the ad campaign, which makes a striking case for a very significant issue. But the cause of equal rights will be served even better with a deeper understanding of the algorithmic forces at work.

For starters, Google no longer returns many of the autocomplete results in the ads. There are a number of factors involved here. Autocomplete constantly changes as a result of the volatility of the Web and based on how people use autocomplete itself. And Google removes some hot-button suggestions. (Disclosure: I used to work for Google, though not on autocomplete.) Top autocompletion results like “Jews are not white/rude/smart/awesome” and “Muslims are coming/the worst/exempt from Obamacare/not terrorists” suggest that some vastly more offensive notions have been removed. Indeed, Google’s policies state that they will remove hate speech completions, among others. Google steadfastly refuses to autocomplete even the final letters of “Muslims are terroris”—autocomplete has been tweaked to never complete that phrase, albeit only on google.com and google.co.uk (google.fr and google.com.eg, for two, complete it immediately). Other prevailing bigotries, which I won’t repeat here, also fail to complete.

For some terms, autocomplete is turned off altogether. “Bisexuals are” and “lesbians are” have no autocomplete suggestions. On the other hand, there are suggestions for “Gays are bullies/the new blacks/wrong/born that way” and other, more bigoted permutations, so the restrictions are somewhat piecemeal and arbitrary. My best guess here is that “bisexuals” and “lesbians” don’t autocomplete because they are terms more closely associated with porn than “gays.” (Most sexual terms don’t autocomplete.) And as we saw above, different restrictions are applied on different international Google portals.

In contrast to a few weeks ago, Google now refuses to complete “women shouldn’t have righ” and “women need to be put in their plac” up to the final letter. So some of those autocomplete suggestions in UN Women’s ads have now been quashed, presumably as a result of the ad campaign. In fact, the campaign may have forced Google’s hand. After seeing the ads, countless people no doubt searched for the phrases in the ads and clicked on the sexist completions, setting up a nasty feedback loop that reinforced the popularity of the searches—not what UN Women intended.

While the autocomplete restrictions may imply that Google is masking just how bad things are, there are also causes for hope. The top search results for “women shouldn’t have rights,” if you type it in completely, are now dominated by pages about the ad campaign. The sheer volatility and self-modifying nature of the Web makes it difficult to pin down prevailing notions for any great length of time. Autocomplete and search results are very sensitive to so-called “freshness,”—all the better to pick up sudden trends—so they use less long-term hysteresis (the dependency of a system on its past states) than you might think.

Of the top results that aren’t about the UN Women ad campaign, not one of them unequivocally promotes an anti-woman position. Some are websites attacking the anti-woman positions, such as an atheist blog on Patheos that quotes and ridicules a Baptist preacher’s misogynistic sermon at great length. Others are debate websites that tend to come down on the equal rights side. One is a Yahoo question, “Reasons why women shouldn’t have equal rights?” posted by a high school girl looking for anti-woman arguments for a school debate. (“Being a girl, I obviously don’t agree with this.”) Most of the respondents say they’ve got nothing. The worst it gets is a troll-infested forum on bodybuilding.com, which, despite being described by poster KingOfChaos as “heavily populated by males who like to think of themselves as ‘alpha’ or dominate over women,” still has a number of sentiments such as “IRL most sane ppl think that women should have equal rights.”

The bodybuilding forum is more the exception than the rule, however. Consider “women shouldn’t go to college,” a phrase whose results have been less impacted by the ad campaign. The top result is a relentlessly dumb but reasonably civil article on ultraconservative Catholic website Fix the Family, which defensively gives the reasons why a woman going to college is a “near occasion of sin.” Most of the rest of the results on the first page are devoted to quoting and ridiculing Fix the Family. (However, Emily Yoffe’s controversial column about college women drinking shows up, too, if you don’t put the search phrase in quotes.)

The No. 2 result is Lindy West’s article in Jezebel critiquing the Fix the Family article. It is significant. First, let’s put things in perspective. In terms of site popularity, Alexa ranks Fix the Family deep in the high 300,000s, a bit below independent academic publisher Prometheus Books and significantly below Web magazine the Public Domain Review. So this is not a well-known website. Jezebel, on the other hand, is ranked three orders of magnitude up at an enviable 527, right around Daily Kos (503) and approaching Salon (374), though still a ways behind Slate (229).

By quoting from and linking to Fix the Family, Jezebel vastly raised Fix the Family’s Google profile. West’s piece helped elevate “women shouldn’t go to college” far higher into the autocomplete results. Google’s automated algorithms do not easily distinguish different motivations for putting text on a webpage, because when it comes to understanding human language, computers are stupid. If “women shouldn’t go to college” appears three times in a Jezebel article, regardless of the disapproving context, then that phrase will become more salient in Google’s algorithms. Google does not distinguish an approving link from a disapproving link; it just sees that Jezebel has linked to Fix the Family. The link from an important site to an obscure site makes the obscure site more important, lifting it up in search results.

There is a way to mitigate this effect: You can use the “rel=nofollow” attribute in links, which tells search engines that the link should not have an effect on the link target’s ranking. In other words, you don’t want to pass your site’s reputation onto the target. (Wikipedia and YouTube use nofollow on most outgoing links.)

Still, Jezebel played a significant role in raising the autocomplete likelihood of “women shouldn’t go to college”—possibly a greater role than Fix the Family itself. There is not a clear-cut answer here. While it’s good to call out occasions of bigotry, it should be weighed against the danger of raising the profile of the bigots and their views.

In my best estimate, just in terms of gaming Google, Jezebel’s West made the wrong call in quoting the Fix the Family site so extensively and devoting a whole article to it. The cost of raising their profile outweighed the benefits of exposing their troglodytic views. From a purely strategic point of view, it would have been better to write up a story concerning female empowerment rather than female subjugation. The topic is frequently more important than the editorial position.

Of course, this very article contributes to the phenomenon, so I’m hardly innocent here. The same lesson applies as it does to the UN Women campaign and West’s article: To Google and to the Internet, sometimes your opinion matters less than what you’re talking about. Regardless of my own opinion of Slate, my editor would probably prefer that I not quote Google’s top autocomplete: “Slate magazine is terrible.”