Tech kerfuffles can be so confusing. There has been some media froth over USA Today’s recent report that Google is considering replacing third-party cookies with their own “anonymous identifier” for tracking consumers’ Internet activity. But much of the major media coverage has been misleading and incomplete—often not mentioning, for example, that Apple has already made such a switch and usually skimming past the corporate panopticon that monitors our Internet activity.

Part of the problem is that the articles tend to skirt over what a cookie even is, so let’s begin there. Quickly: A cookie is an arbitrary chunk of data that a website asks your browser to keep and update on your computer or device across multiple visits to that site. Originally intended to store user information such as usernames and authentication data, cookies quickly came to be used to track a single user across multiple visits. Classic browser cookies come in two basic flavors: first-party and third-party. Third-party cookies are those set not by the site you visit (say, Slate), but by some other site (say, an advertising network such as DoubleClick).

So if you’re on a Slate page with an ad provided by DoubleClick, DoubleClick can access the DoubleClick cookie, not the Slate cookie, and update it to reflect that you saw an ad on a particular Slate page and maybe even clicked on it. Thus, DoubleClick can track you across any site that serves DoubleClick ads. If I read an article on Slate about men’s makeup, then DoubleClick may notice that and show me ads on Salon for men’s makeup.

Since people who change the default settings on their browsers are a distinct minority (a 2009 study put it at 10 percent, though it has probably grown since), those settings make a huge difference. Most browsers enable third-party cookies by default; some, like Google’s Android browser, don’t even give you the choice. (Disclosure: I used to work for Google and I’m married to a Googler.) A few browsers, like Apple’s, turn off third-party cookies by default. Firefox intends to block them by default but keeps postponing it.

But because of these inconsistencies and limitations, third-party cookies are not ideal for tracking a user’s activity across multiple devices. Google’s reported consideration of an “advertiser ID” follows Apple’s switch to the “Apple ID for Advertisers,” which was its replacement for third-party cookies. Such advertiser IDs are complicated beasts, and they don’t represent any significant improvement in consumer privacy. In fact, they make blocking third-party cookies less effective as a privacy mechanism and place the control of privacy into the hands of the company controlling the ID—in this case, Apple.

The significance of the Google story, then, is not about consumer privacy. The cookie fight represents a power struggle between advertising companies and the two leviathan distribution channels of Web and mobile, Google and Apple. The advertisers don’t want any more power to be centralized in the hands of Google (or Apple, but especially Google). Google and Apple want to sort out and consolidate the current mess of tracking and advertising technologies—by setting the terms themselves.

Apple is a less menacing foe for advertisers, because Apple is not in their business. So when Apple introduced the “Apple ID for Advertisers” as a replacement for third-party cookies and device identifiers, advertisers grumbled about the hassle but made the switch. Google, however, is very much an ad man—advertising has constituted more than 95 percent of its revenues for the past decade. So when Google—and its DoubleClick ad-serving division—makes a move to change Internet advertising, rival advertisers get worried. Another ex-Googler, Ari Paparo, speculates that in the worst case, Google could offer its AdID only to advertising partners that meet restrictive terms of service.

The problem is that no one in this power struggle is advocating for consumers’ rights to make informed decisions about how they’re being tracked and what information is being maintained on them. Out of the box, nearly every computer or smartphone is set up so that multiple companies can and will track your activities across large numbers of websites that they don’t own.

Let’s say that your seemingly simple goal is to prohibit any tech or advertising company, from Google to Apple to Bob’s Ad Exchange, from tracking your activities across websites that they don’t own. It’s a reasonable request but nearly—nearly—impossible to achieve. The truth is that cookies are really just one head of the hydra, and not even the most insidious one. Even with third-party cookies turned off, one site has plenty of other ways to let other sites know what you’re up to. Most Web pages are not atomic entities but crazy quilts of scripts and images from up to dozens of different sites. A typical Web article will have ads provided by several networks, each on different domains, a comments system provided by another third party, Twitter and Facebook integration, and analytics code to track site visits.

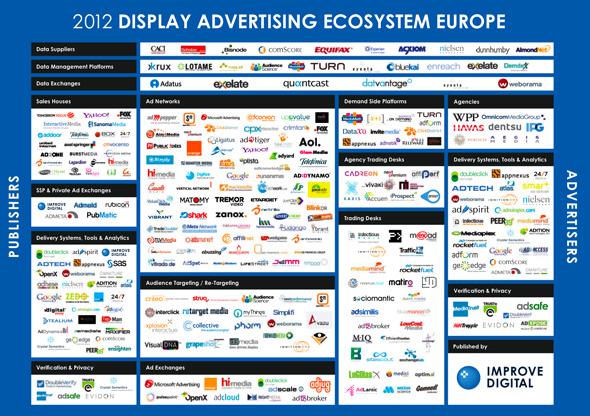

So most any commercial website is sure to loop you into this byzantine network of ad networks, ad exchanges, data exchanges, and trading desks. Research by KnowPrivacy indicated that more than 88 percent of websites inform Google of your visit for advertising, analytics, or some other purpose. The Amsterdam-based firm Improve Digital put together this chart of the major players as of last year.

Courtesy of Improve Digital

All of these companies are involved, one way or another, in tracking consumers to target ads. Third-party cookies are only one of their many tools.

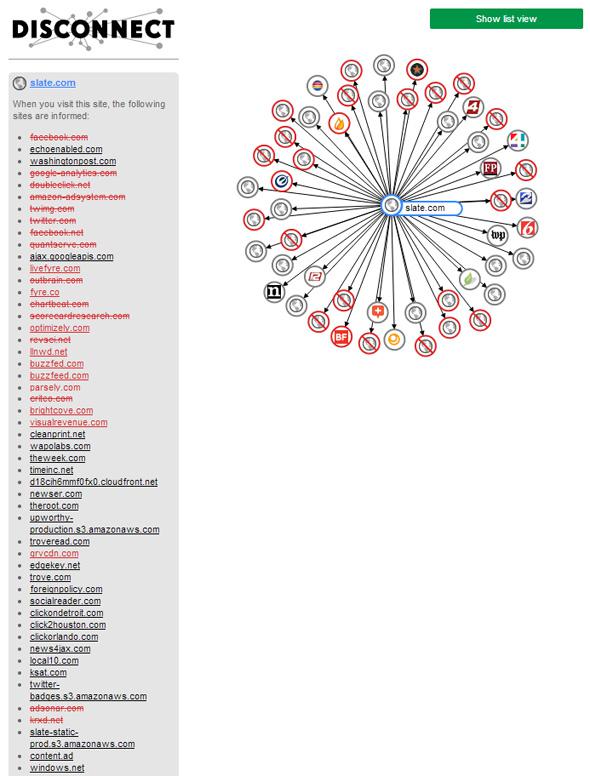

A quick trip to a typical Slate article shows that this single page contacts about 50 other sites, as visualized by the privacy extension Disconnect. (Lest you think that I’m biting the hand that feeds me, Slate is typical among high-traffic sites with advertising.)

Courtesy of Disconnect

Some of these contacts have nothing to do with tracking and are harmless. The page may just be loading content, images, or videos stored on another domain, like Amazon’s CloudFront. But many track you from site to site, from Facebook to DoubleClick to Outbrain. As Disconnect wryly states: “Red circles are known tracking sites. Gray circles aren’t but may still track you.” It came as news to me that Slate has anything to do with Click2Houston.

Ironically, Google, with its fat margins and market dominance, can better afford to give users more control over tracking than most third-party advertisers: Google offers an ads settings manager as well as a DoubleClick cookie opt-out browser extension. It also participates in the user-unfriendly AboutAds Opt-Out project, a coalition of 115 companies that allow you to excuse yourself from Interest-based advertising—though they say nothing about tracking. Unfortunately, there’s a catch-22: The AboutAds Opt-Out uses third-party cookies, so you must enable them for the opt-out to “work.”

I wouldn’t trust the industry initiatives. The much vaunted but mostly ignored Do Not Track header is basically a joke. Some of the opt-outs merely promise not to use your data, even though they still collect it (just like the NSA!). And I wouldn’t bank on Google not backsliding on what privacy choices they have provided. Companies change, as with the rollout of Google Buzz in 2010, which publicly revealed parts of your private Gmail address book to the world, a blatant violation of Google’s long-standing privacy policy.

Google, I imagine, will assure advertisers that they won’t use their AdID advantage to restrict the competition unfairly. You can understand why advertisers might be hesitant to trust them. But I feel little pity for the advertising companies who seem to care less about privacy than Google does. (Google’s record on privacy and security issues, while absolutely problematic in the case of Buzz and their desire for Google Plus to be an identity service, has at least been better than Facebook’s or Microsoft’s.) There’s really no point to consumers taking a side. What consumers can and should do is learn how they’re being tracked and make clear—through informed choices—what is and is not acceptable. And tech journalists can and should step up to help them.

In Part 2 later this week: how to protect yourself from tracking.