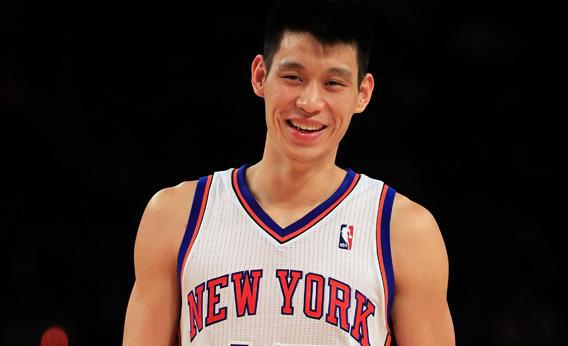

Perhaps it was inevitable that a Jeremy Lin pun would eventually breach the boundaries of good taste. Last Friday, after the Lin-fueled New York Knicks had their seven-game winning streak stopped by the lowly New Orleans Hornets, ESPN.com’s mobile site posted a game recap and Lin photo alongside the headline “Chink in the Armor.” The phrasing was only up for around 30 minutes, but that was plenty of time to aggrieve a rainbow coalition of fans and commentators, who declared it a bad choice of words at best and a smirky, passive aggressive racist dig at worst. ESPN quickly apologized and fired the contrite headline writer. The network also handed out a 30-day suspension to anchor Max Bretos, who had used the same phrase on air earlier in the week.

ESPN’s efforts are commendable, but these incidents suggest that it’s time to retire chink in the armor from the lexicon for good. Yes, I know that phrase has no racial connotations, but it uses the same exact word as the racial slur, for God’s sake. Having been called a chink a few times in my life—an Asian-American rite of passage that usually coincides with puberty—I don’t like hearing it, regardless of context, any more than a homosexual might like hearing the word for a bundle of kindling.

I cringed during the last presidential campaign when the Huffington Post wrote about “the chink in Obama’s armor.” (We presumably already knew about the chink in Hillary Clinton’s armor: disgraced fundraiser Norman Hsu, no relation.) I cringed when ESPN posted the same headline during the Beijing Olympics on a story about the U.S. men’s basketball team. And I shook my head when my shit-stirring former editor at the Seattle Weekly headlined a 2008 blog entry about the city’s resident baseball star “A Chink in Ichiro’s Defensive Armor.”

And I cringed last week when ESPN’s Bretos asked Knicks great Clyde Frazier if Lin had any “chinks in his armor.” I think most people, including me, chalked it up to an unfortunate and ill-timed turn of phrase, one that’s as much a cliché in the sports world as overcoming adversity. I didn’t think he needed to be suspended. And the fact that Bretos’ wife is Asian does help his defense. But doesn’t Bretos’ suspension suggest that we’re better off not using the word at all?

Chink dates back half a millennium to Middle English, a delightfully onomatopoeic word for a narrow opening or fissure. It’s also an agreed-upon slur, although those origins aren’t as clear. One theory is that it refers to the phenotype of Asiatic eyes. Or it might stem from the sound created by Chinese workers as they hammered railroad ties during America’s westward expansion. Or it’s a derivation of China or the Qing dynasty that reigned when the country first opened itself to the West.

Chink’s long history shouldn’t protect it from obsolescence. There’s a precedent for retiring offensive-sounding words from everyday usage. A quick search reveals that there has been but a single use of fagot in the New York Times since 1981 (compared with hundreds before). Dyke has quietly morphed to dike when describing the hydrological feature common in lowland countries. There’s also a rumor that the Dallas Morning News banned niggardly after negative reactions to its appearance in a food review in the 1990s, though Editor-in-chief Bob Mong tells me that it’s not true. Nothing in the Morning News’ style guide would prevent its use, but, because “it’s not really in the vernacular” and has acquired “explosive qualities,” Mong says, most editors would shy away from it. “You’d have to have an awfully good reason to use it,” he explains.

In 1999, David Howard, a white Washington, D.C., agency director, famously resigned amid the outcry following his use of the word niggardly in reference to a budget matter. For all the moaning about political correctness run amok in the reaction to Howard, who was later rehired, it pretty much took niggardly out of the public lexicon. Except when quoting sources or in stories referring to the Howard incident, the Washington Post has used niggardly only once since 1999; the term appeared dozens of times from 1990 to 1999. And for all the arguments that it’s a perfectly good word, I’m still waiting for the editor who dares to pen a headline describing one of President Obama’s policies as niggardly.

And yet the Post has printed chink more than 20 times since April 15, 2008, when it ran a story about the controversy surrounding a Philadelphia restaurant named “Chink’s Steaks.” The founder, not Asian, was given the nickname as a child for “his slanty eyes.” The story explained that “the problem is that the term ‘chink’ is every bit as racist and hurtful to Asian Americans as ‘the n-word’ is to African Americans.” So if mere homophones can be editorially quarantined, why not a certain homonym, too? (Same goes, I’d argue, for spic-and-span and gobbledygook.)

As a writer, my sensitivity to chink causes no small amount of cognitive dissonance. But this isn’t an argument against free speech. It’s not shrinking the language—it’s evolving it. Sadly, there is no analogous slur for white people to help explain what it feels like to be subjected to one, nothing that succinctly and pejoratively diminishes you just for the color of your skin. But I bet if such a word did exist, you wouldn’t see it in headlines.

It should be pointed out that when Jeremy Lin was 15 years old, his Xanga handle was “ChinkBalla88.” I still don’t like it, but it’s different when he uses it, just as it’s different when African Americans use the N-word. Chinese-pop superstar Wang Lee Hom has tried to make chink edgy and cool, referring to his music as “chinked out” and encouraging the use of chink in place of nigga.* A few years ago, Chinese-American rapper Jin put out a track called “Still a Chink.” But thankfully as far as I’m concerned, these attempts to reclaim the word haven’t taken off. And if headline writers would oblige, we just might be able to wipe away the word completely.

Correction, Feb. 22, 2011: This article originally stated that Wang Lee Hom is a Canto-pop superstar. He sings more often in Mandarin than in Cantonese. (Return to the corrected sentence.)