Before Tim Tebow erased the rest of the weekend from memory, there were three other NFL playoff games on Saturday and Sunday. In two of those games—Lions-Saints and Falcons-Giants—a handful of fourth-down gains and stuffs made the difference.

There were three big fourth-down tries in the Saints’ win over the Lions, all of which ended in the Saints’ favor. In New York’s win over Atlanta, three critical fourth-down attempts went the Giants’ way. It’s no surprise that in both instances, the team that won on fourth down won the game. The coaches that made the right probabilistic calls, however, were not always the guys that got rewarded.

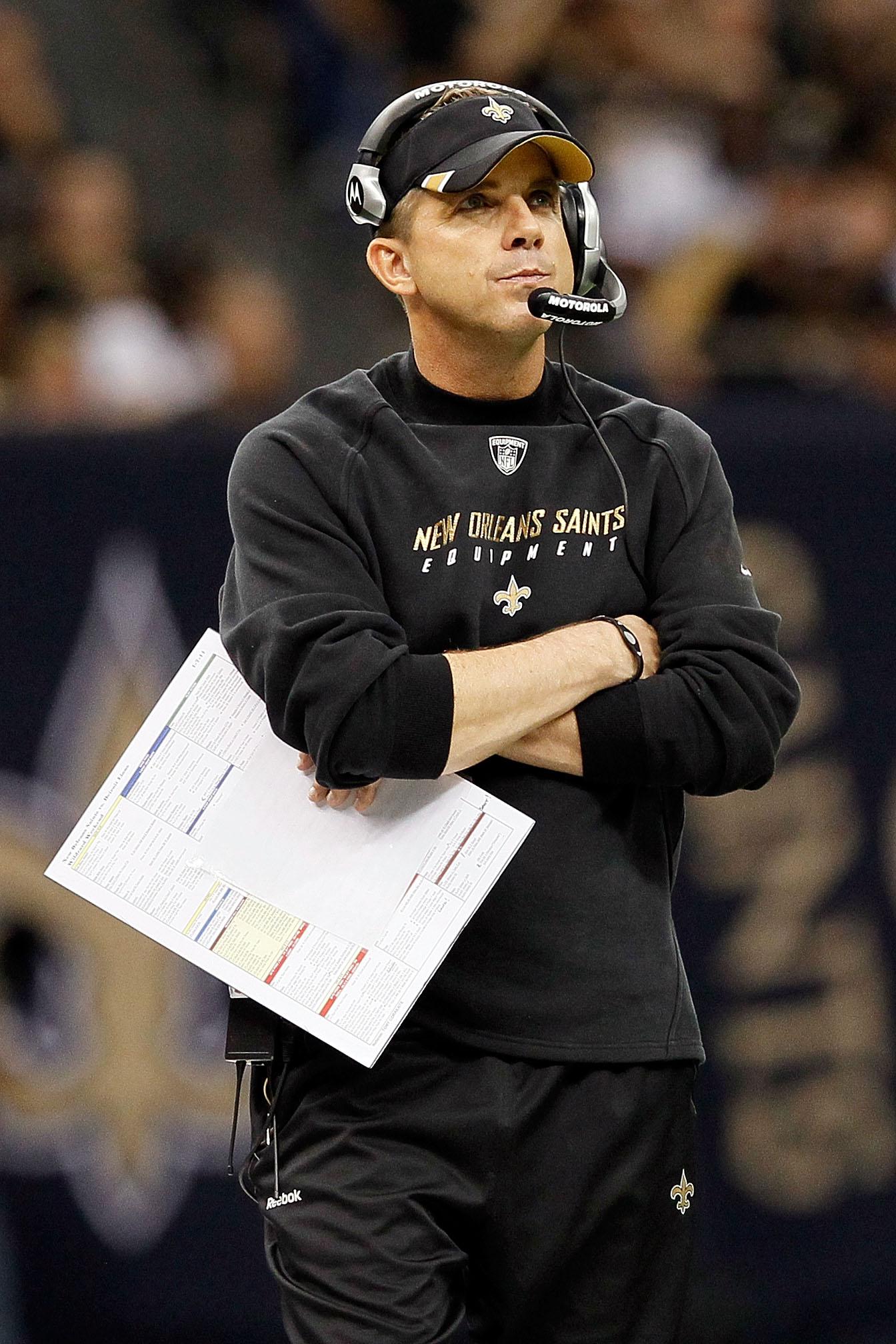

In the Lions-Saints game, Sean Payton reaped the benefits of his fourth-down smarts. New Orleans went 3-for-3 on fourth-and-short conversions, all of which led to scores. In the most audacious case, Payton had Drew Brees run a quarterback sneak with the Saints on their own 38-yard line and clinging to a 17-14 third-quarter lead. This was the correct move—by going for it, Payton increased the Saints’ win probability from 0.63 to 0.65—but it was a decision that was ripe for second-guessing, one that would’ve swung the game toward Detroit if New Orleans had failed to convert. But the Saints made it, and they ended up with a comfortable 17-point win. (In the end, the Saints faced only four fourth downs all game. They converted three, and the other was a kneel-down at the Detroit 5 to end the game.)

In Week 10 of the regular season, Falcons coach Mike Smith got burned for making a similarly bold decision. In a crucial divisional game against Payton’s Saints, Smith decided to go for it on fourth-and-1 in overtime from deep in his own territory. New Orleans stopped Michael Turner’s run attempt, and the Falcons lost on a field goal a few plays later. Even though Smith took a beating in the press, he apparently wasn’t fazed by the experience. To his credit, he was as punt-averse as ever with his team’s season on the line. And again, unlike Sean Payton, he wasn’t rewarded for his rational decision-making.

On the first play of the second quarter of Sunday’s playoff game, the Falcons eschewed a field-goal attempt, going for it on fourth-and-inches from the New York 24-yard line. Attempting the field goal there would have cost the Falcons, dropping their win probability from 0.62 to 0.59. The Giants stopped Atlanta’s quarterback sneak, but then blundered their way to a safety three plays later—the Falcons’ only points of the game. In the third quarter, Atlanta faced another fourth-and-1 from the New York 21. Again, a Matt Ryan sneak failed, and this time the Giants followed up by scoring a touchdown to extend their lead to 17-2. This second fourth-down attempt was just as smart—kicking at that point would have dropped Atlanta’s win probability from 0.29 to 0.28. (Although these numbers might seem small, the percentages mount over the course of a game.)

The Giants, by contrast, took the lead after converting a fourth-and-1 from the Atlanta 6-yard line. That New York drive came after Smith, oddly, declined to go for it on fourth-and-1 from the New York 42-yard line. The Falcons punted to the Giants’ 15, for a net of only 27 yards. It took the Giants all of four plays to move the ball past the 42, where they would have had it in the event of a failed Atlanta conversion. This was an obvious go-for-it situation for Atlanta, a case where it’s too far away to attempt a field goal, and a punt wouldn’t net many yards. Between the opponent’s 45 and 30, in most combinations of score and time, it makes sense to go for it when you have 10 yards to go or fewer. On fourth-and-1, it’s an absolute no brainer.

There are many doubters when it comes to four-down football. If you’re in that camp, indulge me in a quick thought experiment. Let’s imagine a football world where the punt and field goal had never been invented. (Sorry, Ray Guy and Jan Stenerud.) In this universe, there would be no second-guessing: Teams would go for it on every fourth down.

Then one day, some smart guy invents the punt and approaches a head coach with his new idea. “Hey coach,” he’d say, “instead of trying for a first down every time, let’s voluntarily give the ball to the other team.” Our coach would be incredulous at this suggestion. “You want me to give up 25 percent of our precious downs for just 35 yards of field position? Do you have any idea how difficult it would be for us to score?” And the coach would be right.

Since that’s not how the game evolved, our thinking about fourth-down strategy is a lot different. But as the sport has changed, with offense securing a firm upper hand over defense, coaches need to rethink their fourth-down orthodoxy. Accounting for interceptions, teams netted around 3.5 yards per pass attempt in 1977, back when many of today’s head coaches were playing and learning the sport. In the modern game, teams are almost twice as productive when they throw the ball, netting close to six yards per passing attempt. As it gets easier for offenses to move down the field, possession (and maintaining possession by going for it on fourth down) becomes more important and field position becomes less important.

To understand this, consider an extreme example. Field position would be completely irrelevant to an offense that scored a touchdown on every play, regardless of where the ball was on the field. You would do anything you could to avoid punting to that offense—you’d even go for it on fourth-and-99 if you had to. Dial that example back a few notches, and you have the Saints offense, and even the Lions offense at times. When you can’t stop the other team, your best hope is to prevent them from getting the ball. That explains why the Lions attempted an onside kick with five minutes to go in the fourth quarter and with all of their timeouts remaining. The baseline numbers would suggest that was premature, but considering how Drew Brees was playing, it was likely the right gamble.

I think coaches like Sean Payton and Mike Smith are spearheading a slow evolution in fourth-down strategy. Elite offenses, like those in New Orleans, Green Bay, and New England, move the ball so easily that kicking is being marginalized. Plus, opponents who can’t score so effortlessly are forced to take ever greater risks to beat them. We’re witnessing a fundamental transformation in the sport, and the teams that are aware of it and can best take advantage of it will be the winners.