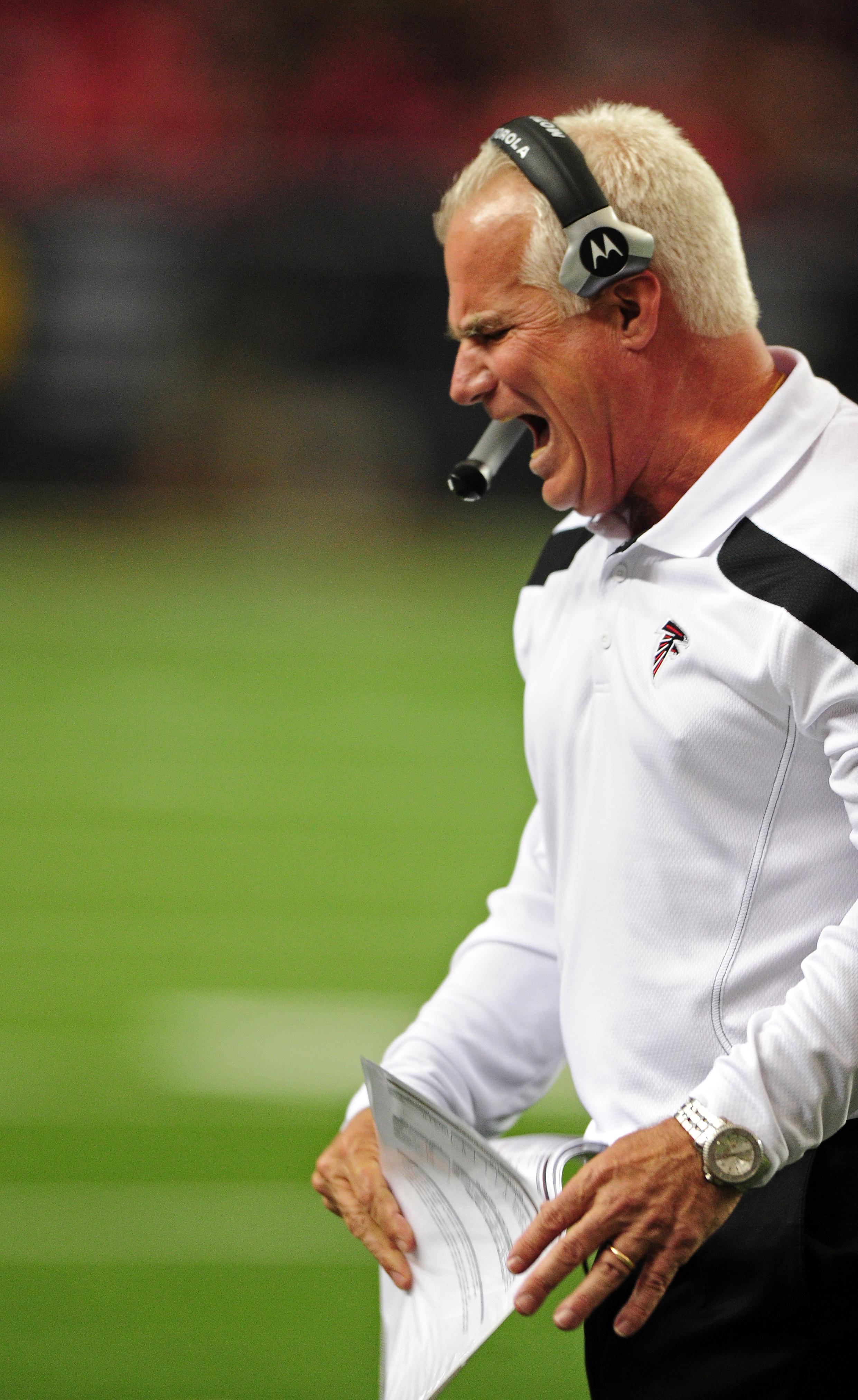

To answer your question, Barry, the Falcons’ defense won’t be upset that Mike Smith “didn’t show faith in them” by deciding to go for it on fourth down. All players on an NFL roster live in the same toy box: offense, defense, special teams. Coaches pull out the toys they want to use, then throw them back in the box. The toys know they don’t get to choose when.

So no, I don’t believe anyone in a Falcons uniform was offended by Mike Smith’s decision. It was overtime. Four quarters of NFL football is tiring and brutal, let alone four quarters of defending the Saints’ offense, which is No. 1 in the league. Add another quarter on the back end, and men are looking around at each other hoping someone makes a play and ends it. Drew Brees can’t be held at bay for long. Plus, the Saints’ run defense is suspect and Michael Turner is really good. Let’s go for it. We’ll get it.

As a player, I loved when my coach decided to go for things. Go for the trick play. Go for it on fourth down. Go for the blocked punt. Whatever it is, players like aggressive decision-making in their coach, because they are aggressive decision-makers, too. The natural divide that exists between coaches and players in the NFL narrows when the coach shows some guts.

But is the fourthdownulator a joke? No, no, it is not a joke. I just checked. It’s very real. So real that our weekly roundtable consults it, or other similar -ulators, to discuss the sanity of a coaching decision. But statistics are dirty, lying liars, and trusting them to explain the reasons why teams win is a dangerous game.

But that won’t stop us from trying. And arbitrary statistical analyses are not reserved for media and fans. Teams have detailed studies, too. They know all the tendencies, to varying degrees, and have included a good amount of this information in the weekly game-plan books they pass out to players. For example, the Falcons’ playbook probably had the fronts, stunts, coverage, and blitz-tendency percentages for every single down and distance, formation, and personnel group the Saints defense has faced over the last two seasons. Aside from the quality-control coach who was forced to compile it, it is likely that no one else looked at it.

Those pages were always left uncrinkled in my game plan. Why do I need to know what blitz they do 15 percent of the time against a three-receiver set on second-and-5-to-8? What will that knowledge do for me? What information will it replace? Will it help me or hurt me? Is an athlete, or a coach for that matter, at his best when he is untethered from rules and probabilities and -ulators, or is he at his best when he has learned every shred of statistical information about his opponent?

I’ve always believed the former. Eric Mangini believed the latter. I was only in Cleveland for one week, but as I wrote last year, I was there long enough to figure out that his coaching style was so interactive as to be intrusive. He peppered his players with fourthdownulator-esque studies, made them memorize those figures, then called upon them in meetings and forced them to stand and recite them. Players were visibly shaken by the process. This was not the football they knew. They had notes scattered about their laps and desks, nervously hoping they wouldn’t be asked to stand and tell Mangini what percentage of the time field goals are made by a left-footed kicker from the right hash-mark facing south with an east-to-west wind in the second quarter of Thursday night games in November. It’s hard to play your best with these things on your mind.

Mangini was a bad head coach. He couldn’t reconcile his scientific approach to the game with the real-time lack of science that was needed to play it. He took it too far and lost his team. Mike Smith won’t be doing that. And even though, in this case, the fourthdownulator agreed with Coach Smith, he would never use it because it can’t be trusted in the moment. The fourthdownulator doesn’t know what Mike Smith knows about his team, about the feeling in the stadium that day, the look in his kicker’s eye, the week of practice. Those things matter.

Because if Smith ever did consult a probability chart, he might get beat by an opposing coach who trusted his gut. Like the guy sitting at third base on a blackjack table and hitting his 12 with the dealer showing a 6. Idiot! But then he catches a 9, the dealer flips a 6 to reveal a 12, then pulls a king and busts. Nice hit, man!

The head coach must trust his instincts and hit against the probabilities from time to time if he wants to leave his mark on the game. Conservative, predictable coaches are a dime a dozen. Surprise onside kicks are dangerous and laugh-out-loud stupid if they don’t work. But if they do work, you’re a damned genius, Sean Payton.

Mike Smith hit on 12. And he busted. But maybe he took the dealer’s bust card, too. Maybe it’ll come back around. And doesn’t the guy who’s playing the probabilities always seem like he’s having a miserable time doing it? Hunched over his cards, sweating, breathing heavily, waiting to lose it all and go back to his room early. And blaming the “book” for his losses.