When 36 million live viewers saw Pierre Thomas’ consciousness leave him before he hit the natural grass, I think we were as taken aback as the taciturn announcers. Not just because of the Bugs Bunny physics and obvious human damage involved, but because battle had officially been joined. The Saints’ drive had looked unstoppable, and the Packers were surely going to dominate the next day’s game, and we were on our way to a flag-football NFC Championship. Pierre Thomas going down in a heap was the first indication that the league’s elite defenses would be more of a brick wall than a speed bump for the unstoppable offenses; it wouldn’t be the last.

A month ago I would have said the Packers and Saints would meet for a trip to the Super Bowl, and I would have put money on it. Heck, lots of people did. But the favorite lost (twice), in instructive fashion (twice) to a team with a diametrically opposed emphasis (twice), and it was obvious why—yet we never saw it coming. I could have sworn the emperor had clothes this time! We don’t learn from our mistakes. We get so glamoured by a flashy, clinical offense that we let ourselves believe it could overcome any flaws on the other side of the ball. And then that buzz saw offense runs into a playoff-caliber D, and it gets slowed down just a bit, and there’s nothing left behind the scenery.

Green Bay and New Orleans, we should have known better. And if I did know better, I’d discount New England right now. Defense wins games. It’s been drilled into us since birth and printed on bumper stickers, and damned if we don’t regularly get handed examples. So why are the Patriots still near odds-on favorites to win the whole damn thing, despite a league-worst defense? Because they have the Tom Brady juggernaut on offense, and recent history tells us that can sometimes be enough.

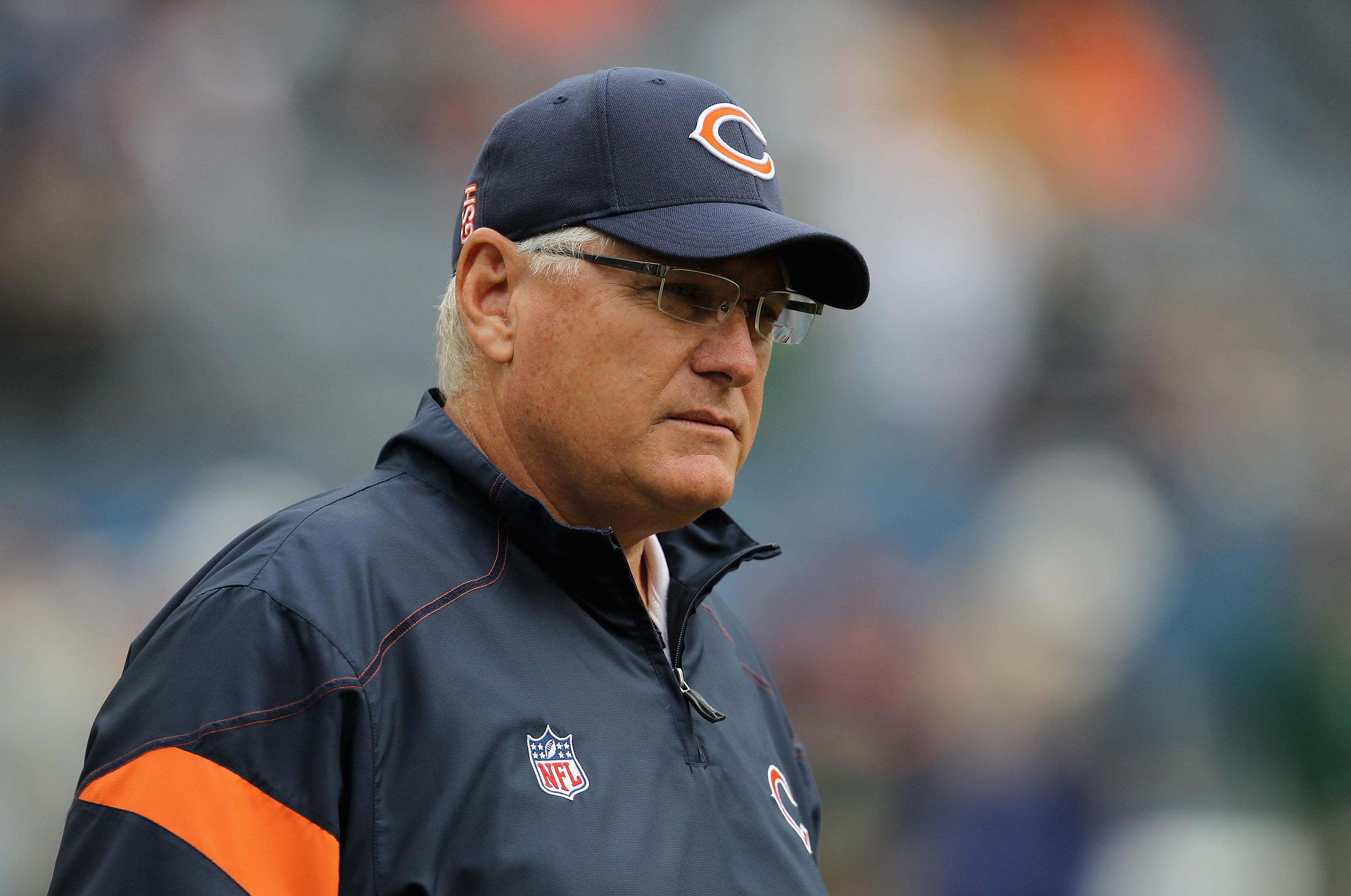

The cartoonishly prolific offenses of the world have a very powerful patron saint, and if the Patriots are smart, they’ll light candles tonight at the shrine of the now-retiring Mike Martz. Have faith in the passing attack, my sons.

Offense vs. defense is the heart of football. No other sport is so Manichaean in its split, to the point of employing totally different humans to work each side of the ball. Normally, the opposing forces evolve in lockstep, each adapting to the other in a matter of halves. But once in a while, the offense can make a leap forward, leaving defenses years behind. Never physically; the corporeal arms race remains hopeless. But further up the brainstem, where Mike Martz proved himself one of the few truly revolutionary offensive minds of our times, and bequeathed a philosophy that will long outlive a career that ended yesterday.

Martz was the man behind “The Greatest Show on Turf,” the high-scoring turn-of-the-millennium Rams micro-dynasty. Like its ‘70s and ‘80s forebear, Air Coryell, it was more than a team nickname. The Greatest Show on Turf was a specific offensive scheme, one that continues to inform and even define the NFL today. How to describe it? It’s the Madden offense, or maybe backyard football. “Everyone go deep.” It’s much more, of course, but the best way to understand it is on that viscerally vertical level. Martz’s playbook wasn’t primitive, but it was damn primal.

The original Greatest Show scheme, which was born while Martz was the Rams quarterback coach and wide receiver coach, was his own take on an old Don Coryell system. So it’s a taxonomic descendent of Air Coryell as well as a spiritual one—relentless and vertical in a way Bill Walsh’s bastard stunted version never was. The turf show thrived on five wide, spreading the secondary and ensuring man coverage somewhere. Backfield in motion, to confuse the defense with a variety of looks. A capable, veteran offensive line, to give the deep threats time to get sprung.

It’s not complicated stuff, but the sheer number of route permutations means everyone needs to have his playbook down pat. Those Rams, not least of them the coldblooded Kurt Warner, were a rare assemblage of specialized cogs. Perhaps more so than most schemes, Martz’s baby needs a very specific environment to thrive. (If you’re wondering why he’s is retiring now, read a wholly depressing account of Martz explaining that the Bears would never ask Caleb Hanie to do “that St. Louis kind of stuff.”) It allows for and requires a whole arsenal of offensive weapons, most of them available on any given play. The height advantage receiver. The speedster. The crafty white guy with good hands. The shifty pass-catching running back. The dangerous tight end. The transcendent quarterback. And, inevitably, a woeful defense, its weaknesses hidden behind turnover numbers inflated by opponents desperately trying to catch up. Green Bay, New Orleans. And New England, where Bill Belichick remains almost in awe of Don Coryell.

In the end, Martz’s own offense won only one Super Bowl, as defensive adaptations were hastened by Warner’s injuries and the Patriots’ discovery of their own out-of-nowhere pocket demigod. Still, his Rams showed an entire generation of play callers not that it should be done by relying solely on an air attack built around a preternatural QB, but that it could. And just as Joe Gibbs’s Redskins found gold with the map drawn by Coryell for the Chargers, the latter half of the decade has seen Super Bowls go to teams throwing caution and coverage to the wind: the Patriots, the Colts, the Saints, the Packers.

So why not the Patriots again? Why shouldn’t they be the favorites, given recent history? Because no matter how things shake out, they’ll still have to get through two of the NFL’s best defenses.