In the days leading up to the Green Bay Packers’ Thursday night victory over the Chicago Bears, the team asked its fans to join the players in a demonstration of unity—locking arms—during the national anthem. The Packers’ call for solidarity came after President Donald Trump urged NFL owners to fire any player who kneeled during the national anthem. In response to the team’s request, one made in part by its star quarterback Aaron Rodgers, many fans expressed anger over what they perceived as the Packers’ disrespect for the flag, the anthem, and the military—even though black players, taking a cue from Colin Kaepernick, have made clear that they are kneeling in protest against police brutality and racism.

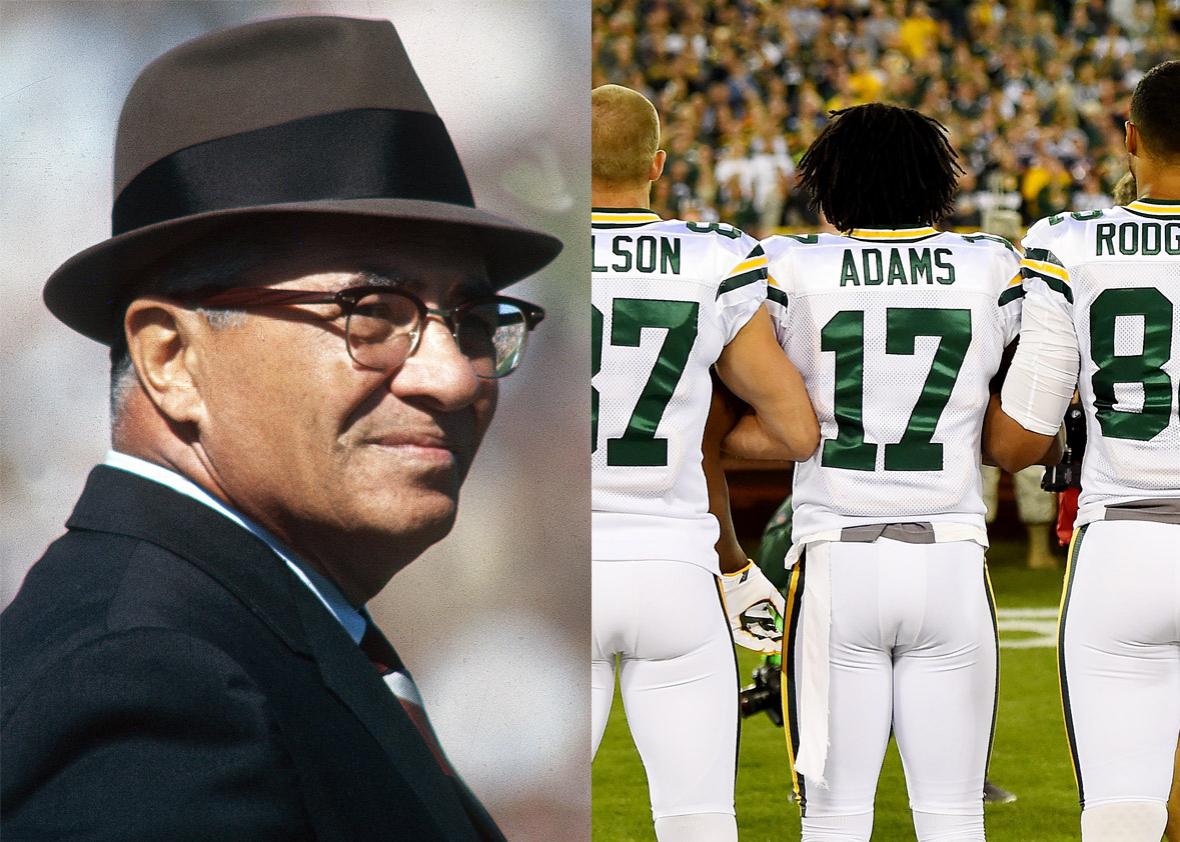

Yet critics maintain that the Packers have betrayed not only the country but also the pater familias of football: legendary Green Bay coach Vince Lombardi. Venting their displeasure with the Packers’ demonstration on social media, self-proclaimed super patriots lamented that Lombardi must be rolling in his grave in shame that his Packers refused to honor the flag. (“The Star-Spangled Banner” has only been played regularly at sporting events since World War II.) Country music singer Charlie Daniels, who has said he is boycotting the NFL due to the anthem protests, tweeted, “Wonder how Vince Lombardi would have reacted to his players kneeling during the anthem.”

Though not universal, the fan backlash against the Packers raises more questions about Lombardi’s legacy: Why has he become a prominent symbol of law and order in the age of Trump? And why do so many Americans hold such an unwavering belief in the patriotic significance of football? Perhaps it’s because President Trump himself has invoked the memory of Lombardi as the kind of leader he admires: a winner whose unquestioned authority made him seem all the more heroic to his supporters. (As he said to the Washington Post about once seeing Lombardi scream at a player, “I realized the only way Vince Lombardi got away with that was because he won.”) Perhaps for some fans, the demonstrations by black athletes and their white teammates shatter the notion that football—and the country itself—are unscathed by racism. Or perhaps, as Lombardi biographer David Maraniss has suggested, Americans continue to look to “St. Vincent,” a coach who succeeded in an age of protest and social unrest, because he reminds them of leadership that seems “irretrievably lost,” a man of action who believed in God, country, and family.

In the late 1960s, no football coach commanded more respect than Lombardi, who had led the Packers to five NFL championships. Before 1967, Lombardi’s last year as coach of the Packers, most of his speeches focused on football as a metaphor for life: the importance of character, discipline, sacrifice, and mental toughness. He rarely spoke about specific political controversies or foreign policy, even as the American presence in Vietnam was rising. Yet as the nation became increasingly roiled by conflicts over race, war, and campus unrest, Lombardi became more concerned about the country’s direction. He was especially worried about the growing rebellion among America’s youth and their lack of respect for authority.

In response to what he saw as the problems of society, Lombardi developed “the speech,” an address that spoke to the frustration he shared with Middle America about “a complete breakdown of law and order and the moral code.” Lombardi first delivered his new speech on Feb. 8, 1967, in New York City at the American Management Association. Though he was a lifelong Democrat, his speech seemed to suggest that he was turning to the right. Studying the world around him, the demonstrations by the New Left, the counterculture, and antiwar activists, Lombardi feared that “everything has been done to strengthen the rights of the individual and at the same time weaken the rights of the church, weaken the rights of the state, and weaken the rights of all authority.” Perhaps, he added, “we have too much freedom.”

For Lombardi, a man who cherished the sanctity of institutions, excessive individualism and the disruptive forces of protest threatened his vision for a civil society. He was not the only one. Later that fall, in an article published in Reader’s Digest, Richard Nixon asked the prevailing question weighing on the minds of many: “What Has Happened to America?” Though Nixon would not start using the term “silent majority” until 1969 to define those who “do not demonstrate, who do not picket or protest loudly,” his Digest article clearly identified the symptoms of “national disorder—the decline in respect for public authority and the rule of law in America.” He pointed to the summer race riots in inner cities “as the most visible” cause. The signs of America’s contempt for authority could be found everywhere: “in the public attitude toward police, in the mounting traffic in illicit drugs, in the volume of teenage arrests, in campus disorders and the growth of white collar crime.” The Silent Majority had become exasperated with protesters “disrupting parades, invading government offices, burning draft cards, blocking troop trains or desecrating the American flag.” Aside from the draft cards, it’s a list of complaints one might not be surprised to hear today.

In the emerging Nixon’s America, Lombardi became a voice for traditional values and patriotism, the very principles that he believed were under attack. In 1967, he welcomed a group of Green Bay women who organized “Pride in Patriotism Day” at Lambeau Field, an event organized as a “flag-waving answer to young antiwar demonstrators and draft card burners.” The women provided more than 50,000 flags to fans that day, covering the entire stadium with the stars and stripes. Before kickoff a college choir sang, “This Is My Country” and “God Bless America.” This was not simply patriotism. It was politics. During the 1960s, the Packers and the NFL explicitly embraced the government’s position in Vietnam, turning stadiums into arenas for promoting U.S. foreign policy. It was during the late 1960s that NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle, a political conservative, mandated that all players stand at attention during the anthem. After watching the partisan spectacle on national television, he sent Lombardi a telegram that simply said, “Wonderful.”

Yet despite his clear sense of what was going wrong, Lombardi offered only vague solutions for the country’s problems. He admitted that he knew little about the various protests movements, but in his mind they all represented a threat against order and a preference for factionalism over unity. In an age of complex social problems, his message of respecting authority and the rule of law offered appealing relief for those yearning for simplicity. What the country needed most, he argued, was better leadership. And by 1968, he had become so popular on the speaker’s circuit that both political parties considered him leadership material, potentially a vice-presidential candidate.

There were few men whom Richard Nixon respected more than Lombardi. As a political candidate and later as president, Nixon wanted to capitalize on football’s popularity to build a coalition with Middle America, fusing sports and politics. Throughout his political career, he appeared at games, met with fans, coaches, and players, and presented himself as an expert on the sport. He believed that pro football fans made up the Silent Majority and that the game’s most successful coach could bring the country together—and possibly win him votes. But when his adviser John Mitchell learned that Lombardi was a Kennedy man, progressive on civil rights and gun control, Nixon realized that he had misjudged him.

Yet Lombardi’s politics never fit neatly into a single ideological box. A man of contradictions, he embodied a mixture of conservative and liberal impulses. Critics viewed him as an emblem of authoritarianism, conformity, and narrow thinking. In an Esquire profile, Leonard Shecter painted him as an egotistical tyrant. But for all his flaws, Lombardi was also deeply compassionate, thoroughly committed to improving society. He may have embraced a certain idealized notion of social order, but it was not one that valorized the status quo of racial inequality against black Americans.

Lombardi deplored prejudice of any kind. As an American of Italian descent and a devoted Catholic who had grown up in Brooklyn, New York, hearing all sorts of demeaning slurs, Lombardi would not tolerate bigotry on his team. In 1959, during his first season as head coach of the Packers, he lectured the team on intolerance. “If I ever hear nigger or dago or kike or anything like that around here, regardless of who you are, you’re through with me,” he said. “You can’t play for me if you have any kind of prejudice.” Recognizing that the black players on his team experienced discrimination in Green Bay, an overwhelmingly white town, Lombardi made it known among local taverns, restaurants, and landlords that if his players were not treated equally that there would be hell to pay.

Lombardi viewed his team as a family, which made him the father. Stern though he was, he loved his players, black or white. And he made sure to protect them. Traveling through the Jim Crow South in 1960 for exhibition games, the integrated Packers were denied service at hotels, forcing the black players to stay at separate establishments. Lombardi vowed that he would never again allow the black men on his team to experience such humiliation. In the future, he declared, every Packer would stay together. It was a kind of political protest, one that did not garner headlines but certainly didn’t go unnoticed among his players. Racism, he reminded them, would not divide the team.

His progressive racial views were shaped not only by his experience as an Italian American, but also by what he experienced firsthand in the South. According to Maraniss, when the team visited Winston-Salem, North Carolina, for a game against lily-white Washington, Lombardi, bronzed from the summer sun, was refused service in a local diner because the hostess thought he was a black man. Although he could never know what it meant to be black in a segregated country, he at least had a window into the daily degradations black Americans encountered.

His greatest Packer teams depended on full integration. When he came to Green Bay as an assistant coach from the New York Giants, the Packers had only one black player: Nate Borden. Lombardi understood that he could not construct a championship team by ignoring black athletes. As head coach and general manager, he drafted and recruited some of the greatest black players in the league. By 1967, the Packers fielded a squad with 13 black athletes, including All-Pros Willie Davis, Willie Wood, Dave Robinson, Herb Adderley, and Bob Jeter.

But Lombardi did not simply play black athletes. He treated them the same as his white players, even when disciplining them. “It never enters my mind that I’m being chewed out because I’m a Negro,” Dave Robinson said. “The important thing is everybody gets equal treatment.” Traditionally, head coaches assigned hotel rooms based on race. Lombardi, however, made sure that room assignments were not made on the basis of skin color. In 1967, Harry Edwards reported, the Packers were the only NFL team with such a policy.

Looking back, Vince Lombardi’s treatment of black players helped forge the Packers’ reputation as the most democratic team in the NFL. Although we can’t be certain how he would respond to players kneeling during the anthem, what we do know is that if something mattered to his players then it mattered to him too. An advocate for social justice, Lombardi listened to his men, believing that their voices needed to be heard when it came to racial equality. For Lombardi recognized the humanity of every man on his team. “If you’re black or white, you’re part of the family,” he explained in 1968. “We respect every man’s dignity black or white.”

Regardless of a player’s race, background, or political views, he said, a team stood as one. His message resonated on Thursday night when Aaron Rodgers and his teammates locked arms in a demonstration of “love over hate and unity over division.” Football, Lombardi believed, had the power to enlighten, to bring together black men and white men. “If you’re going to play together as a team,” he said, “you’ve got to care for one another. You’ve got to love each other.”

Love over hate. That was Vince Lombardi.