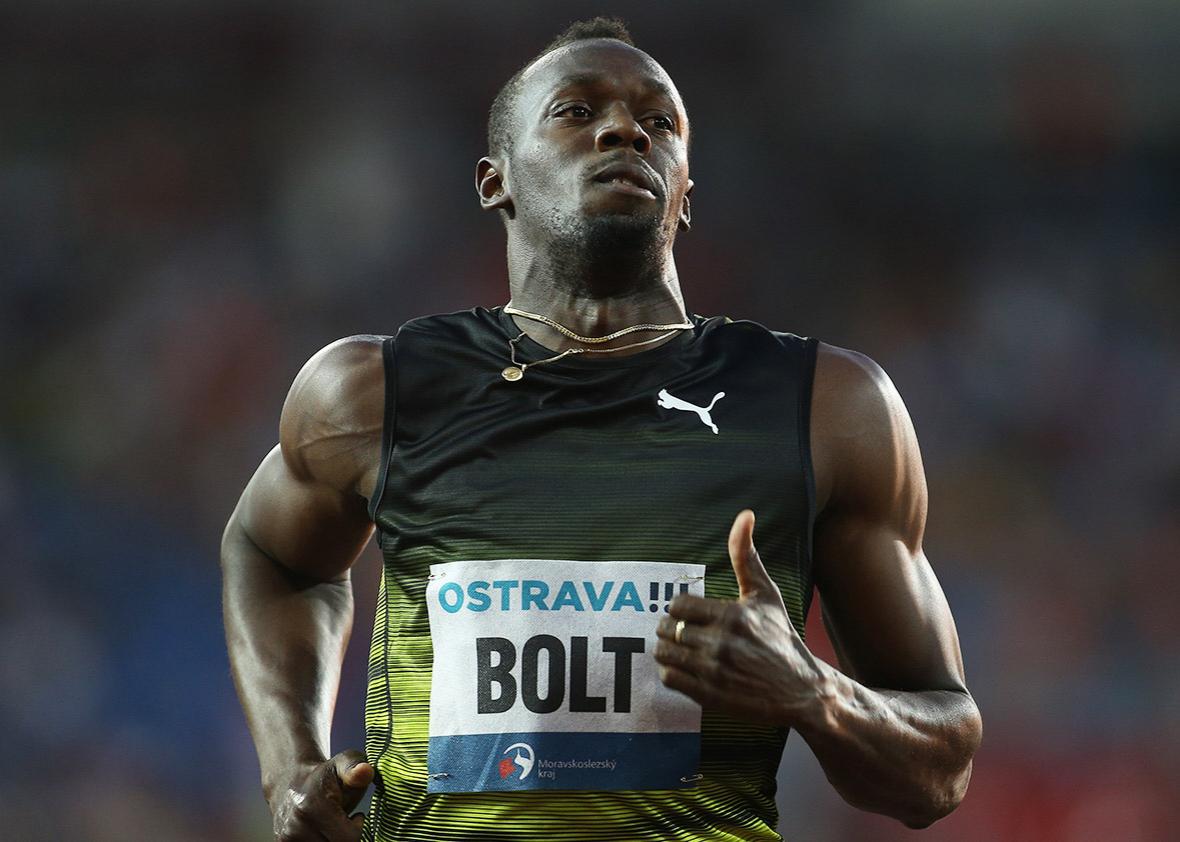

Usain Bolt is the only person to win both the 100 and 200 meters at three Olympic games. He is also the only person to do this at two Olympic games. Bolt has broken five individual outdoor track and field world records, three of them his own. He has run three of the five fastest 100-meter races and four of the six fastest 200-meter races in history. As Bolt gets set for the World Athletics Championships in London, the final meet of his beyond-illustrious career, we should be grateful for all the memorable moments the world’s fastest man has given us. We should also be ingrates and ask: Could he have run faster?

Bolt has an uncanny knack for making the incredibly difficult look easy—like Muhammad Ali coming off the ropes, like Westley fencing with his left hand, like James Joyce writing Ulysses from Paris. It’s only natural to wonder, then, if he could have done more. His midrace celebrations, his apparent aversion for practice and affinity for parties, his less than sensible diet—he reportedly ate 1,000 Chicken McNuggets in 10 days during the Beijing Olympics—all suggest history’s greatest sprinter might’ve had a little bit more in the tank.

After Bolt breezed to a 9.69 world record in the 100 meters at the 2008 Olympics, jogging and chest thumping across the finish line just days before his 22nd birthday, his coach Glen Mills made headlines with his claim that Bolt would have hit 9.52, at worst, if he had just run through the line. Scientists took on the task of projecting the time that might have been, with most concluding that 9.52 was, at best, a slight exaggeration. Bolt, though, made that claim look less sensational when he tore through his own world records at the world championships in Berlin a year later, posting 9.58 in the 100 and 19.19 in the 200. Still, Bolt would never reach the 9.52 that Mills estimated, nor, for that matter, the 9.4 that he himself predicted. He would never best those world records that he set in Berlin, when he was not yet 23 years old.

“We haven’t seen the 2009 Bolt since 2009,” says Peter Weyand, the director of the Locomotor Performance Laboratory at Southern Methodist University and a leading expert on the science of sprinting. When I asked Weyand about Bolt’s early peak, he told me that, although 22 or 23 is not an unusual age for a sprinter to top out, he would have predicted more after Bolt’s 2009 performances.

While recent research from Weyand’s lab concluded that Bolt’s stride is abnormally asymmetric, Weyand says it’s unlikely this asymmetry held Bolt back in any way. He does point, however, to several aspects of Bolt’s form that are considered unorthodox and potentially suboptimal.

Weyand says the limiting factor of sprint speed is not turnover—how quickly a sprinter moves his or her legs—but the force, or impulse, the runner exerts into the track. We can think about impulse in two parts: the force generated when a sprinter’s legs are in the air and the force a sprinter applies by striking the track with his foot—a sort of hammer-and-nail relationship. Bolt’s footfalls—the hammers hitting the nails—are nearly perfect, but his windup—the way he swings those hammers—is not what physiologists see as ideal.

This video of a sub-10 second 100-meter runner, taken in Weyand’s SMU lab, provides an example of the traditionally accepted “ideal” form for a sprinter: low heels on the back side, high knees in the front, driving forward.

Weyand says this ideal technique is best embodied in Asafa Powell, Bolt’s former Jamaican teammate and the sprint king dethroned by Bolt’s first 100-meter world record. Bolt’s technique, by contrast, resembles that of a gazelle: heels clicking backward and up, nearly tapping his rear as his spikes point to the sky with every stride. And yet, inexplicably, each of Bolt’s steps manages to produce more than 1,000 pounds of force, allowing him to take advantage of his 6-foot-5 frame and finish a 100-meter race in about three fewer strides than his competitors.

Weyand admits he doesn’t know whether Bolt’s unorthodox form slows him down. “He may suffer no ill consequence from not conforming to the working ideal,” he says, conveying an uncertainty that speaks to the many mysteries still facing the burgeoning field of sprint science. The challenge here, as the South African physiologist Ross Tucker told me, is that the field is still “so much in its infancy that we can’t say for certain that X is good and Y is not.” In a sport where every little thing matters, tiny adjustments can be dangerous. That said, it certainly seems possible that by adopting something closer to Powell’s technique, Bolt could generate more power during the time his legs are in the air, ultimately putting more separation between himself and his competitors.

Bolt has taken heat for his running style in the track community. Former 200- and 400-meter world record holder Michael Johnson has said Bolt could run 9.4 in the 100 and break 19 in the 200 if he cleaned up his form. “Technically he is not the best. Technically he is a bit all over the place,” Johnson said in 2014. Johnson elaborated to the BBC at the 2015 world championships, critiquing Bolt’s upper body movement: “He doesn’t have lateral stability, so you will see a lot of rocking back and forth.” He also criticized Bolt’s starts, saying that the sprinter is “clunky” and “all over the place” when he comes out of the blocks.

It’s worth noting that Bolt could’ve run faster without changing his form one bit. In 2012, Cambridge physicist John D. Barrow determined that Bolt could run 9.45 in the 100 meters if he improved his reaction time at the gun, raced at altitude, and ran with the maximum allowed tailwind of 2 meters per second at his back. (It’s worth noting that Bolt ran both of his world record 200-meter races into headwinds.) Barrow added that he believes Bolt would have run faster if he’d seen major competition more often, saying, “If there’d been an Olympics every two years … you’d probably have a better world record.” All of Bolt’s world records, barring his first, have come in world championships or at the Olympics. Given more frequent appearances against top-level competition, Bolt would have had more incentive to ride the momentum of his peak 2009 form. Barrow, a scientist and a major track fan, says it’s a little disappointing that Bolt didn’t make more of his enormous potential. Mapping the arc of the sprinter’s career in retrospect, he says, “It really does look like a very sharp rise and then a gradual fall off.”

There are those, however, who theorize that Bolt’s self-described laissez-faire attitude may be one of his greatest assets. Robert Johnson, a co-founder of the running site LetsRun.com, is one of them. Johnson points to Bolt’s training partner Yohan Blake, whom Bolt nicknamed the “Beast” for his preternatural work ethic. Blake has been indisputably brilliant at points in his career—he’s second only to Bolt on the all-time 100 and 200 record boards—but has also been plagued by injury. Meanwhile, Bolt’s relatively lax approach, especially when paired with his coach’s (and his own) insatiable expectations, might have resulted in an ideal workload for the Jamaican champion to stay both fast and healthy.

David Epstein, whose book The Sports Gene examines the genetic basis for Jamaican dominance in sprinting, believes it’s more likely than not that Bolt came close to maximizing his potential. “I don’t think he likes to train as much as the next guy, but I think that’s really good,” said Epstein, noting that athletes with Bolt’s explosive power run the risk of injury by pushing themselves during repeated intense workouts. Bolt’s periods of rest and his relatively light racing schedule may have been optimal for a man of his talents. Epstein described a little-known aspect of muscle physiology known as an “overshoot” phenomenon that he believes Bolt and Mills have used to their advantage. During intense training, a sprinter’s Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers can be temporarily impaired only to bounce back even stronger after a stint of rest. “When you stop doing your most intense and explosive training, there’s a delay—and then you’ll briefly be more explosive than you would ever be again,” Epstein said. If Bolt and his team have calibrated this phenomenon in the way Epstein claims, they may have found a way to exploit Bolt’s rest to catapult him even further ahead of the pack. “He seems to me to be a better peaker than any sprinter who’s ever lived,” Epstein told me.

At age 30—he’ll turn 31 later this month—Bolt’s best days are doubtless behind him. It is a testament to the sprint king’s dominance that his 100-meter and 200-meter times look likely to stand for years to come. Bolt left little reason for suspense over the course of his career. Most of his races looked the same: providing a slight flicker of doubt in the brief seconds after the gun, doubts that washed away quickly as Bolt separated, galloping off on his own, all the while smiling and making it look easy. Since 2008, he’s pretty much been competing with himself. The truth is, we’ll never know how fast he might have gone on a perfect day with the perfect start and the perfect stride.