On Monday at Fenway Park, one or more Boston Red Sox fans allegedly hurled the N-word and a bag of peanuts at all-star Baltimore Orioles center fielder Adam Jones. The next day, Bostonians gave Jones a standing ovation. This gesture—along with apologies from Boston’s mayor, Massachusetts’ governor, and Red Sox management—did not quite solve the franchise’s long-term problem with racist actions and attitudes.

In the aftermath of Monday’s incident, New York Yankees pitcher CC Sabathia told a Newsday writer that he and other black players expect to hear racial epithets every time they play in Boston. And it’s not just baseball. The Washington Capitals’ Joel Ward was on the receiving end of racial slurs when his team faced the Bruins in the 2012 NHL playoffs. And in the realm of less-recent history, the Boston Globe recalled that intruders once broke into Celtics legend Bill Russell’s home and defecated on his bed. Russell’s daughter later recounted the incident in the New York Times as just one example of the racism her father faced in Boston.

The story of race and sports in Boston isn’t just a long list of ugly incidents. As far back as the 1940s, strong-willed individuals have tried to change the attitude of the city and its teams. In that decade, a Boston city councilman named Isadore Muchnick partnered with black sportswriter Wendell Smith to court Jackie Robinson and campaigned to bring black players to the city’s two major-league franchises, the Red Sox and Braves. It’s tempting to imagine that if Muchnick had succeeded, and Boston—not Brooklyn—had broken the color barrier in baseball, Fenway fans might not have showered Jones with abuse on Monday. That’s perhaps generous and overly simplistic, but it’s useful to think about how that long-ago event might have served as an inflection point in Boston’s history, and what that lost opportunity has meant for the city.

Muchnick, a former Hebrew school teacher, served as chairman of Boston’s School Committee, a position that made him the first Jew to hold citywide office. Twenty years before Boston’s infamous busing riots, he was a pioneer in pushing for the desegregation of the city’s classrooms. Some have said his motivation for fighting baseball’s Jim Crow system was a self-interested one, given that his constituency was largely black. But in his book Shut Out: A Story of Race and Baseball in Boston, Howard Bryant reported that this was a myth; per both the 1940 and 1950 census, Muchnick’s district was 99 percent white. His children’s testimonials in that book, and the rest of Bryant’s reporting, point to the city councilman’s genuine desire to desegregate baseball for reasons other than politics.

According to an account in the Times, his push for integrating the Boston teams began when he took over the city council’s speakership in 1943. The Red Sox’s then-owner Tom Yawkey and general manager Eddie Collins were aghast at the idea of a black player joining the team. Yawkey remarked that it would be bad for business as black fans would keep white ones away from Fenway. Collins, who’d played for the infamous World Series–throwing Black Sox team in Chicago, insisted there simply weren’t black players who were good enough to play in the majors. He’d later say that in his 12 years with the club, the Red Sox “never had a single request for a tryout by a colored applicant.”

As the season approached in 1945, Muchnick wielded his power. Then as now, Boston was a Catholic city, and at the time an old law prohibited businesses from holding public events on Sundays. Every year, the Braves and Red Sox received special permits that allowed them to hold Sunday games. Muchnick, however, proclaimed that the issuance of those permits would no longer be a formality. If the teams didn’t give players from the Negro Leagues a tryout, he said, the city would withhold permission to play on Sundays.

Yawkey and Collins relented, agreeing to hold a tryout. On April 16, 1945, a day before opening day, reporters—though none on duty for the Boston Globe—came to see the invited players: Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs, second baseman Marvin Williams from the Philadelphia Stars, and outfielder Sam Jethroe of the Cleveland Buckeyes. All three ballplayers, aware of Yawkey’s and Collins’ views, later claimed to know the tryout was a charade, an event the team held to get a Muchnick off their backs before his campaign affected ticket sales. “We knew we were wasting our time,” Robinson told the Globe in 1972. “Nobody was serious then about black players in the majors, except maybe a few politicians.” A 1997 retrospective on the tryout in the Boston Globe reported that someone from the stands interrupted the tryout by shouting, “Get those n—ers off the field!”

The Baseball Hall of Fame reports that the Braves never held their own tryout. Nevertheless, the city’s National League franchise was still allowed to play on Sundays. In 1950, Jethroe would integrate Boston baseball—and win rookie of the year—when the Braves made him their first black player. The integration of the city’s baseball rosters was short-lived: Three years later, the Braves left for Milwaukee, and the Red Sox continued their refusal to bring in black talent.

Despite the epithets and the dim prospects that the Sox would sign anyone who participated in the 1945 tryout, contemporary reports say the players, particularly Robinson, impressed observers. News of the tryouts spread through the black press, eventually reaching Branch Rickey. The Brooklyn Dodgers’ general manager had been pondering integration for some time. Shortly before the Boston tryout, he held a sham tryout of his own in Bear Mountain, New York, with two Negro League players who were already 35 and 40 years old—and thus too old to bring to Brooklyn. The reports about Robinson’s play in Boston caught Rickey’s attention. Shortly after the tryout, Rickey asked Wendell Smith to broker an introduction. In August 1945, Rickey signed Robinson to a minor-league contract. He spent a year in the minors before debuting at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947, breaking the major leagues’ color barrier nearly two years to the day after his Fenway workout.

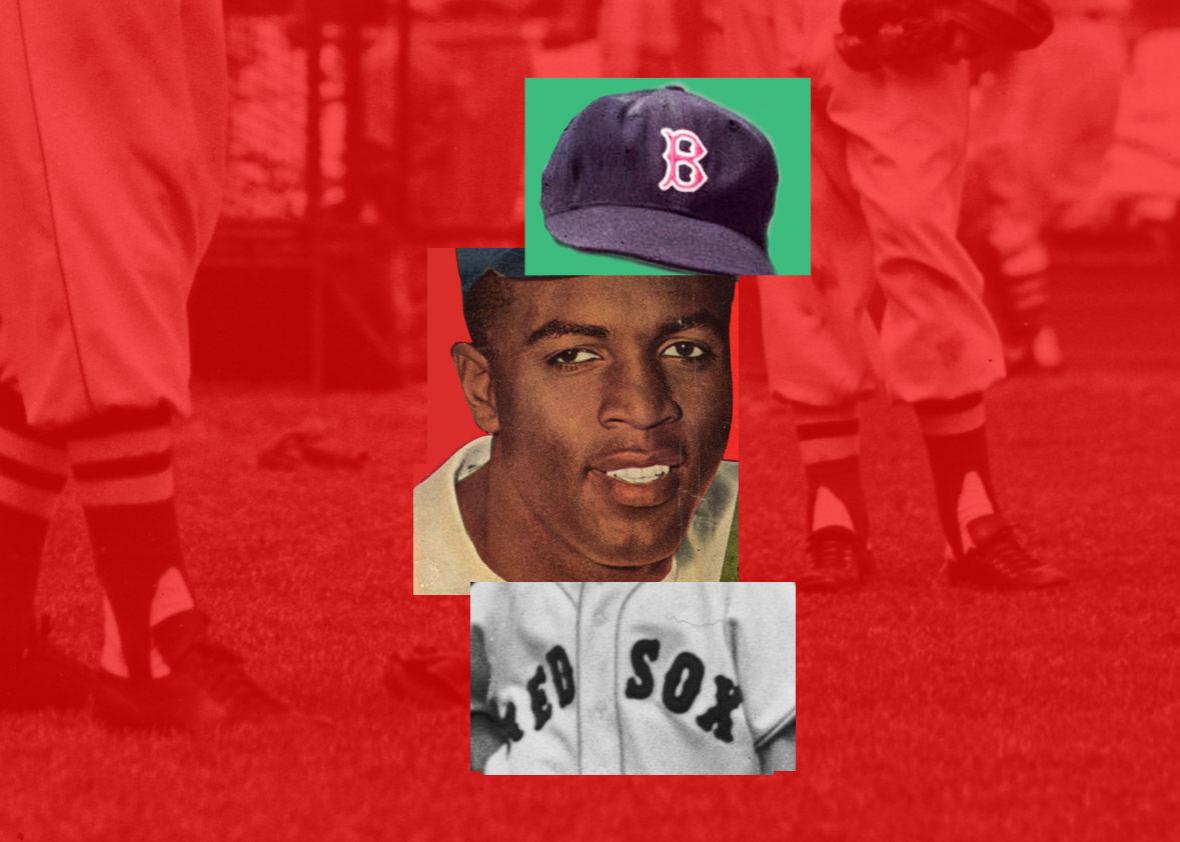

The Red Sox, meanwhile, infamously became the last major league team to integrate, with the signing of infielder Pumpsie Green in 1959. In the years between the 1945 tryout and Green’s signing, Jackie Robinson would win rookie of the year, an MVP award, a batting title, a World Series, and six National League pennants. Around the league, future Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Roy Campanella, and Larry Doby all made their debuts.

Robinson and Muchnick remained friends long after the city councilman’s failed effort to bring the future Hall of Famer to Boston. Muchnick’s children described their relationship in Bryant’s book, saying Robinson would visit often when he was in town to play the Braves, and that the two men argued over the 1960 presidential election, in which the ballplayer supported Richard Nixon over John F. Kennedy on the grounds that the Republican had done more for civil rights. Later, Robinson would send Muchnick a copy of his autobiography with the inscription, “To my friend Isadore Muchnick with sincere appreciation for all you meant to my baseball career … Much of it was inspired by your attitudes and beliefs.”

If the Red Sox had signed Robinson in 1945, one imagines the two men might have grown even closer. More importantly, it’s probable that white Boston sports fans would have had a long, memorable lesson in the hatred launched at black athletes. Realistically, though, Muchnick never had a chance. The Robinson tryout, after all, was a farce; Yawkey and Collins were never going to sign a black player. The city, too, subjected its pioneering black basketball to horrific racial abuse. The Celtics were one of three teams to integrate the NBA in 1950 when they drafted Chuck Cooper. Bill Russell, whom the team drafted in 1956—three years before the Red Sox signed Green—was the league’s first black superstar. “I played for the Celtics, period,” he told his daughter. “I did not play for Boston. I was able to separate the Celtics institution from the city and the fans.”

The fact that fans at Fenway Park gave Adam Jones a standing ovation this week shows the city and its fans have made significant progress in the past 70 years. The fact that the crowd needed to affirm a basic belief in human dignity shows Boston still has a very long way to go.