A version of this piece originally appeared on the blog Very Smart Brothas. It’s reprinted with the author’s permission.

It took roughly a month at Sterrett Classical Academy for me to be known as the best basketball player there, an admittedly considerable feat for a 10-year-old sixth-grader in a school with 14-year-old eighth-graders. It was a status I earned due to a combination of my reputation from playing with the Homewood YMCA and from my exploits during recess and gym class. Unfortunately, I submitted the mandatory physical and doctor’s waivers three days late. And Mr. Simons, Sterrett’s basketball coach, wasn’t going to allow me to try out for the team.

I went home and told my dad. He shook his head, said “OK,” and continued reading the Post-Gazette. The next day, he showed up to the school during lunch time, pulled me out of the cafeteria, and requested a meeting with Mr. Simons (who was also the seventh-grade social studies teacher). We met in the gym.

Calmly, my dad apologized for the lateness of the physical and requested that Simons allow me to try out. He appreciated the apology but said something about the rule being the rule and denied the request. My dad had another idea:

“How about this? You play my son one-on-one right now. If he beats you—and he will—he’s allowed to try out. If not, you’ll never hear from me again.”

Mr. Simons turned beet red and started to stammer.

“Sir, that’s not really necessary.”

My dad was steadfast.

“Oh, yes it is.”

Sensing that this was a no-win situation—and also likely intuiting that if my dad was this confident about my abilities, a bending of the rule would be worth it—he relented. By the end of the day, I was on the team. I didn’t even have to try out.

Several months later, while I was playing in a spring AAU tournament at Reizenstein Middle School, my dad noticed a team with preternaturally skilled and disciplined 11-year-olds running through a bevy of complex, college-level plays and zone presses. He learned that these kids were from St. Barts and that they played a diocese schedule during the season and an AAU schedule in the spring and summer that had them playing up to 100 meaningful games a year.

Later that week, he convinced my mom that they should a) take me out of Sterrett and enroll me in St. Barts the following school year and b) allow me to repeat sixth grade because I was young for my grade—since my birthday falls a day before New Year’s Eve, I was always the youngest person in every class I was in—and repeating the year would give me an advantage athletically and socially.

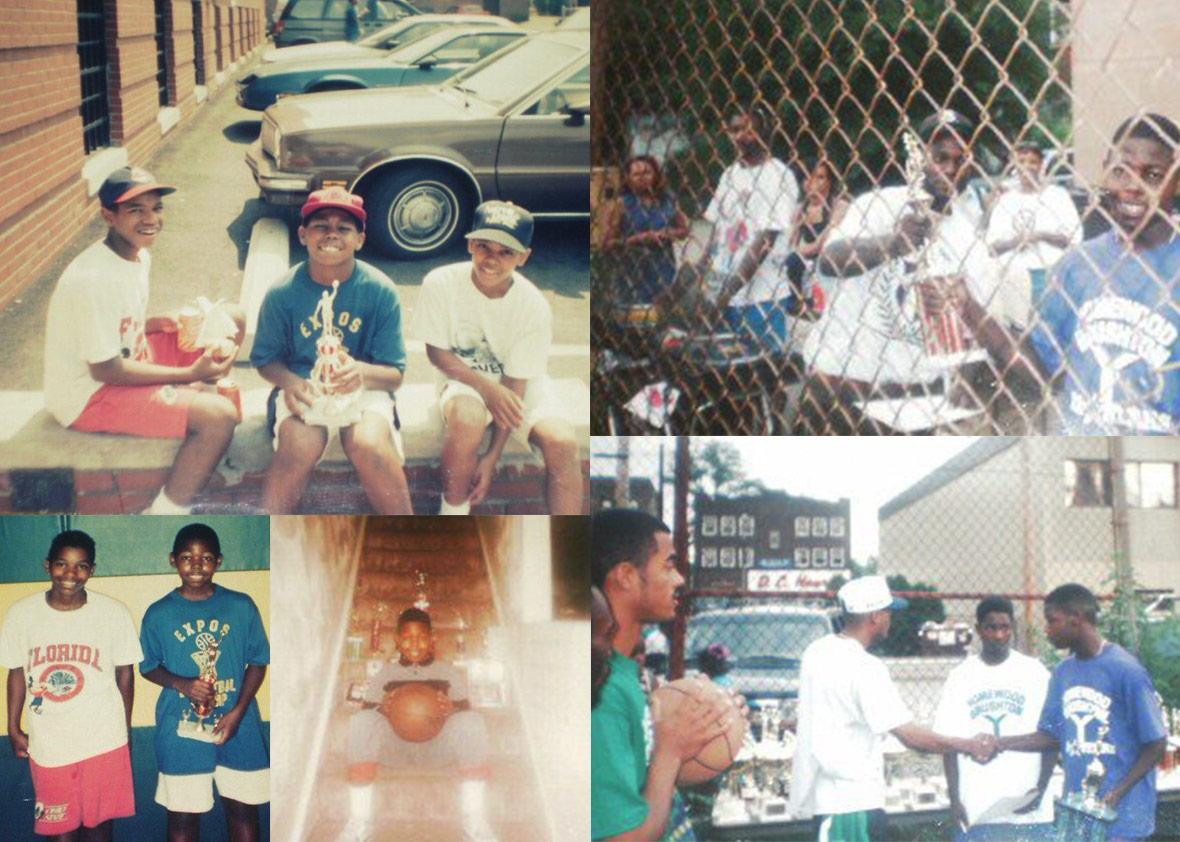

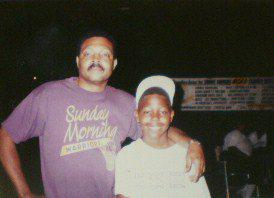

I have countless stories like this about my dad. The 200 shots a day we’d take on the courts behind Peabody High School the summer of ’89 to upgrade my shot from a slow-release, 10-year-old-appropriate set shot to a full jump shot released over my head and at the peak of my jump. The basketball magazines and almanacs he’d buy me when I professed an interest in devouring as much about the game and its history as I could. The mornings I’d watch him play in the Sunday Morning Warriors basketball league at the Y, where I’d sneak on the court at halftime to shoot foul shots.

Even today, his Facebook page is home to dozens of snapshots of those moments. Usually me receiving some award from some camp or league or game, and him behind the lens, making sure my trophy was facing the camera.

Damon Young

And, of course, sometimes it would just be us.

Damon Young

It is difficult not to see some of my dad in LaVar Ball, the polarizing father of basketball phenoms Lonzo Ball (a projected top-three NBA draft pick), LiAngelo Ball (a high school senior committed to play at UCLA), and LaMelo Ball (a 10th-grader who might already be the most popular athlete in high school sports). And not just my dad, but the countless other black basketball dads found on bleachers at AAU tournaments and modeling perfect triple-threat stances on concrete blacktops in the hood. Shepherding their sons (and sometimes daughters) from court to court and neighborhood to neighborhood. And, if they’re good enough, from city to city, state to state, and school to school. Simultaneously serving as their kids’ drill masters, coaches, instructors, one-on-one opponents, hype men, financiers, advisers, protectors, bouncers, dietitians, jitneys, critics, vision boards, sponsors, and parents. Willing to challenge each and every entity, real or imagined, standing between them and their ultimate goal. Which could be a college scholarship. Or an NBA contract. Sometimes, they’re the only other black faces in the gym (or the league) besides their kids on the court, their presence ensuring that “these white people” don’t try any mess with their boys.

I know that if you sat Lonzo, LiAngelo, and LaMelo down, they’d each have stories about their dad that would mirror mine. And if you glanced through their social media accounts and family photo albums, they’d each have just as many pictures and videos either taken by their dad or with them posing next to him. And I have no doubt they treasure those pics and those memories and those moments as much as I do.

This context both constructs and complicates my feelings about LaVar Ball. Like my dad and the countless other black basketball dads out there, he wants what’s best for his sons. This is undeniable. My dad’s goal was for me to receive a college basketball scholarship. And I did. Mission accomplished. LaVar Ball’s sons are each better basketball players than I was, and his athletic goals for them are understandably and appropriately greater.

Also, I’d be remiss if I didn’t admit to the strain of schadenfreude I experience when a black person challenges and perhaps even upsets the status quo the way LaVar Ball currently is attempting to do. I’m compelled to root for him even if I don’t agree with his methods (I don’t) or even like him very much (I also don’t).

But, those years in those gyms and those courts and on those teams and in those leagues also taught me how to recognize a blowhard and a bully. Which is exactly what LaVar Ball is. And my distaste and disdain for men like him equals the affinity I have for the black basketball dad. I knew men like him, and they are the worst coaches to play for and the worst parents to sit in the stands with, and they very often produce the worst kids to play with and root for. You do not want to be a kid on the same team as the kid with that type of dad. Even if the team is good, he and his parent can be so insufferable and make the game so joyless that you’d rather quit it than win with it.

I look at his attempts to promote his family’s brand with similar ambivalence. He’s not actually wrong to attempt to get in front of the major shoe companies and pursue a lucrative partnership instead of a run-of-the-mill shoe contract. But his Big Baller Brand is GeoCities-level terrible; the only thing worse than the name is the logo, which looks like an actual belt buckle sold at Buckle. Also, while Lonzo is a phenom, he’s not the type of transcendent, LeBron-ish talent who could carry a brand by himself. He’s good but not that good.

Combined, this collection of conflicting feelings has left me not knowing how to feel about him. I appreciate what he’s done for his kids, and I get what he’s trying to do, but I don’t fuck with that dude at all. I want him to succeed, in theory, but I don’t want him to be him. And while it’s true that his diligence has helped each of his boys reach this level of prominence—and receive full athletic scholarships—his efforts and actions now are more than likely hurting them. Lonzo Ball has already been publicly rebuked by each of the major shoe companies, an act that, when considering the abject terribleness of the just-released Big Baller Brand shoes, might cost them tens of millions of dollars. And I’m certain De’Aaron Fox isn’t going to be the last guard to put a little extra effort into washing Lonzo on the court just because of his dad’s bombast.

A month or so ago, I asked my dad how he felt about LaVar Ball. Knowing that he shares my feelings for blowhards and bullies, his answer (“He needs to sit down and shut up”) was predictable. I then reminded him of parents like Earl Woods and Richard Williams, who each faced similar criticisms when they first become national figures but (obviously) were proven to be right. I also reminded him of that time he challenged Mr. Simons to play me.

“Yeah, but that was different.”

“How?”

“I challenged him to play you, not me.”