My love of baseball comes from summers spent in Idabel, Oklahoma, with my grandfather. We would throw the ball back and forth as he told me stories of traveling hours to see Willard Brown and Satchel Paige play for the Kansas City Monarchs. My grandfather told me that the style of play in the Negro Leagues was much different from that in the all-white majors. Paige, a slender 6-foot-4, would lift his front leg high into the sky, delay his windup for a split second, and then throw the ball with incredible velocity and pinpoint accuracy. He was also known for calling in his outfielders and telling his infielders to sit down before striking out the side.

Speaking to the Kansas City Star, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum president Bob Kendrick lamented that “part of what kept Satchel Paige out of the big leagues so long was he was too charismatic of a player.” Only inhabiting a black body could keep a man with so much talent as Paige traveling what he called the “peanut circuit.” This weekend will mark the 70th anniversary of Jackie Robinson integrating Major League Baseball. It is an important event that should be celebrated, but we should do so critically—for while baseball’s powers that be allowed black bodies into the sport, they were not as welcoming to black culture.

Black culture is American culture, and the flamboyance of players in the Negro Leagues was a major part of why that great American institution was so beloved. Unfortunately, as black athletes integrated baseball, major-league players and fans did not embrace much of what made the Negro Leagues unique. Many teams, for instance, warmed up by miming baseball moves with great flamboyance, a practice known as playing “shadow ball.” Players in the Negro Leagues wowed the crowds with their convincing reactions to balls that were, in fact, not there. But when they made it to the majors, shadow ball ceased to exist.

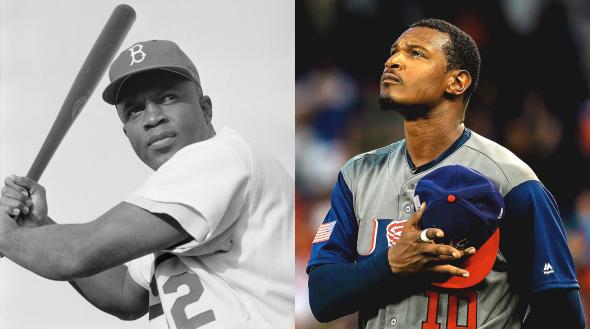

As William Rhoden noted in the New York Times in 2014, Robinson didn’t leave the style of the Negro Leagues behind when he joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. His “speed and daring,” particularly his steals of home, were a trademark of black baseball. “At that time, [white] baseball was a base-to base thing,” Negro Leagues legend Buck O’Neil said in an interview for Ken Burns’ documentary Baseball. “But in our baseball … if you walked, you stole second … you actually scored runs without a hit.” Robinson’s aggression on the base paths infuriated his opponents, particularly the white ones. Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Russ Meyer, annoyed at watching Robinson dance off third base, yelled, “Go ahead you nigger, try to steal.” Robinson did try. He was safe at home.

“Negro League players threatened the established racial order,” Mark Anthony Neal, a professor of African and African American studies at Duke University, told me recently, “not only in terms of taking actual jobs from white ballplayers but in developing a style of play that would transform how the game was played.” It wasn’t just black players that threatened the white-dominated major leagues. A 1960 piece in Sports Illustrated noted that Latin players were considered “hot dogs.” The definition, according to SI: a “player who calls attention to himself, either through his actions or his attitude.” The magazine also quoted an anonymous white player. “You automatically assume any Latin is a hot dog until he proves himself otherwise,” he said.

Nearly 60 years later, that belief is still all too prevalent. In April 2015, Dodgers outfielder Yasiel Puig told the Los Angeles Times that he was going to try to stop flipping his bat into the air after he hit home runs. “I want to show American baseball that I’m not disrespecting the game,” he said. Yet, the Cuban star also added, “If it’s a big home run or if I’m frustrated because I couldn’t connect in my previous at-bats or if I drive in important runs for my team, I might do it. You never know.”

It’s painful to hear a star player with a buoyant personality declare that he’ll try to fit in by curtailing his natural exuberance. Why did Puig feel that kind of pressure? Because white players like Bud Norris, who now pitches for the Los Angeles Angels, say things like this: “We’re opening this game to everyone that can play. However, if you’re going to come into our country and make our American dollars, you need to respect a game that has been here for over a hundred years.” In other words, you can play in our country, but you must adhere to our (largely white) expectations. When you hit a home run, lay your bat down gently. Smile if you want … but don’t show any teeth.

It is a form of cultural colonialization to allow a player to display his athletic brilliance but to prevent him from bringing his culture to the game. Yes, major-league games take place in American cities, but people from around the world populate these ball clubs. That’s why the World Baseball Classic was such a joy to watch. The moment when Cubs second baseman Javier Baez, playing for Team Puerto Rico, celebrated a no-look tag before the play was over wouldn’t have happened in the majors without consequences and repercussions.

For me, though, there was something quintessentially American about this Puerto Rican player laughing and pointing as he tagged out his Dominican opponent. This was the game I grew up hearing about from my grandfather, a man who spoke in glowing terms about the joy black players displayed on the field.

Jackie Robinson may have integrated Major League Baseball 70 years ago, but it was, and continues to be, a white man’s sport. The World Baseball Classic gave us a glimpse of what baseball could be, if only we allowed the men who play it to express the fullness of their humanity.