Stefan Fatsis told a version of this story on Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen in 2014. An adapted transcript of the audio recording is below, and you can listen to his essay by clicking on the player beneath this paragraph and fast-forwarding to the 56:12 mark.

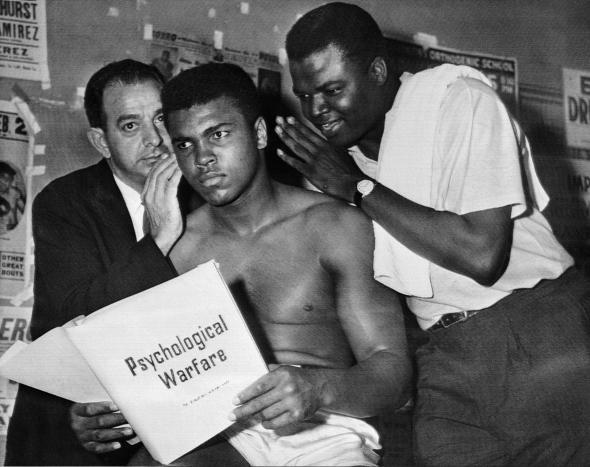

Muhammad Ali’s coming out as an athletic, political, and media star happened in 1964, when the boxer, still using his given name, Cassius Clay, beat Sonny Liston to claim the heavyweight title. But the persona had been in development. During a victory over Doug Jones at Madison Square Garden a year earlier, the announcer Chris Schenkel called Clay “the man who has captured the imagination of everybody across the country,” and noted that celebrities including Lauren Bacall, Jason Robards, Toots Shor, and “Mrs. Bob Hope” were there to see him fight. A few days before that bout, Clay won a poetry reading at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village with a 36-line ode. That poem read, in part: “Marcellus vanquished Carthage, Cassius laid Julius Caesar low/ And Clay will flatten Doug Jones with a mightily muffled blow.” At the coffeehouse he also repeatedly proclaimed, “I’m the greatest.”

The public was becoming fascinated with the media-savvy Clay, and boxing fans were growing enamored of him too. In the eyes of the predominantly white and paternalistic sports establishment, however, the accomplishments of the outspoken young fighter from Louisville didn’t merit such boastfulness. One writer in particular seemed to have it in for Clay: the venerable Arthur Daley of the New York Times. Daley won a Pulitzer Prize in 1956 and wrote an estimated 11,000 “Sports of The Times” columns over 30 years; he collapsed and died outside the Times building at age 69 on his way to write one more. But when it came to Ali, Daley got it spectacularly wrong.

In July 1963, Daley wrote: “Having lowered the boom on an overrated introvert, Floyd Patterson, the destructive Sonny Liston will proceed to do the same to an overrated extrovert, Cassius Marcellus Clay.” Daley called the planned fight an “execution.” He lectured that it was “high time” that Clay “eased off” his boasting. He quoted a “trainer for many champions” who said, “First of all, Clay doesn’t know how to fight.”

Four months later, after Clay and Liston had agreed to fight, Daley called Clay a “loudmouthed braggart“ of “irritating proportions” who had “destroyed his image and antagonized those who normally would be rooting for him.” Clay’s “phony display of childish petulance” during the contract signing—in which Clay pretended to throw a punch at Liston—was “nauseating.” “Most experts are agreed that Sonny should not have the slightest trouble in disposing of a novice like Cassius,” Daley wrote. He speculated that Liston, “mean and cruel by nature,” might “let Clay linger a few rounds so that he could deliver a merciless beating to his tormentor before flattening him for keeps.”

Two days before the fight in Miami Beach on Feb. 25, 1964, under the headline “Boy on a Man’s Errand,” Daley wrote: “On that evening, the loud mouth from Louisville is likely to have a lot of vainglorious boasts jammed down his throat by a ham-like fist belonging to Sonny Liston, the malefic destroyer who is champion of the world. The irritatingly confident Cassius Clay enters this bout with one trifling handicap. He can’t fight as well as he can talk.”

Daley went on to criticize the boxing habits that would come to embody Ali’s in-ring greatness. “The Louisville lip holds his hands too low and he has a rather fatal habit of jerking back his chin to avoid a punch. … [A]ny well-schooled fighter has the know-how to take advantage of this amateurish maneuver … ” Clay won, of course, with a seventh-round technical knockout. And Daley wasn’t pleased. His post-fight column was titled “Another Surprise.” In it he praised Clay’s fight, but used words like “implausible” and “still almost impossible to believe.”

These were more than hot takes gone awry. For older writers like Daley, Clay’s skill and his personality were in fact impossible to believe. When Clay beat Liston, Daley was pushing 60. He had been writing, in overblown prose in the Grantland Rice tradition, seven columns a week for the Times since 1942. Robert Lipsyte, who covered that Clay-Liston fight as a 26-year-old reporter for the Times, told me that Daley wasn’t a bad guy at all. He was just set in his ways; his worldview was formed in more predictable and homogenous times, socially and athletically.

Like other prominent columnists, including Red Smith, Dick Young, and Jimmy Cannon, Daley was offended by Clay “on every level,” Lipsyte said. Clay “pissed on their church, he pissed on their boxing sensibilities, he pissed on their sense of self.” The middle-aged-and-older white sports writers preferred their black athletes tough, quiet, and deferential, like Liston or Joe Louis, whose private peccadillos the press conveniently ignored.

At his news conference the day after the Liston fight, Clay was soft-spoken and modest. “If he sticks to this pose, he can win a vast amount of popularity,” Daley lectured. Lipsyte, meanwhile, figured out what Clay was up to. “At first, [Clay] pleased his predominantly white audience with amiable and measured statements,” Lipsyte wrote near the top of his Times story. The older writers “smiled at one another when Cassius said, ‘I’m through talking. All I have to do is be a nice, clean gentleman.’ ”

But then the tone of the news conference changed and the reporters “began to shift a little nervously” when Clay “put them down” for discounting his chances against Liston. “And finally,” Lipsyte wrote, “there was a trace of antagonism when [Clay] refused to play the mild and socially uninvolved sports-hero stereotype, and began to use the news conference as a platform for socio-political theory.”

Lipsyte told me that, by that point, the old guys had closed their notebooks and left to file their columns or go to Hialeah. One of the remaining writers asked Clay whether he was “a card-carrying member of the Black Muslims.” Clay launched into a disquisition on race and political theory. “Card-carrying? What does that mean,” he railed. “I go to a Black Muslim meeting and what do I see? I see there’s no smoking and no drinking and no fornicating and their women wear dresses down to the floor. And then I come out on the street and you tell me I shouldn’t go in there. Well, there must be something in there if you don’t want me to go in there.”

The reporters still in the room, Lipsyte recalled in his 1975 book SportsWorld, “tended to be the younger, more vigorous, socially conscious liberals of the newspack who felt comfortable talking non-sports and wanted to challenge Clay on the Muslims’ separatist dogma.” The conversation then veered to “civil rights arguments and citizenship arguments and sports idol arguments,” and Clay made what would become a famous declaration: “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be who I want.” The quote was the lede of Lipsyte’s story the next day. It didn’t make Daley’s.

Daley later wrote that he’d preferred the youthful, innocent Clay to the man that Muhammad Ali became. The Clay he had met at the Rome Olympics in 1960 had “cast a spell” and “won me to him instantly with his overpowering personality and boyish charm.” But, the columnist lamented in 1970, “Cassius has changed.” Daley, and other writers, didn’t like that. They didn’t like Ali’s anti-war pronouncements or his religious conversion or his proclamations about the black underclass or his rhyming. They, and millions of Americans, didn’t like that the world was now a different place.

After the 1964 fight against Liston, Clay announced that he had changed his name, become a Muslim, and joined the Nation of Islam. In a prefight interview with Howard Cosell in 1966, Ali attacked his opponent, Ernie Terrell, for calling him Cassius Clay instead of Muhammad Ali. As he pummeled Terrell in the middle rounds, Ali famously screamed, “What’s my name?”

The power of the pen meant sports writers could call Ali whatever they wanted without fear of retribution. While Lipsyte referred to him as “Muhammad Ali” on first reference as early as 1964, it didn’t stick. “Troglodyte editor Abe Rosenthal was emphatic about it being ‘Cassius Clay’ until he changed his name in a court of law,” Lipsyte told me, “but we kept trying to slip ‘Muhammad Ali’ through. And sometimes we did.” When Lipsyte tried to explain the Times’ policy to Ali, the champ told him not to worry. “You just the white power structure’s little brother,” Ali said.

Using “Clay” was a way for writers to let Ali know what they thought of his politics and his religion. Even after the Times finally began calling Ali “Ali,” Daley persisted. The day after Ali beat Jerry Quarry in October 1970, Daley’s column was headlined, “Muhammad Ali Is Back on Top.” On first reference, though, Daley referred to the victor as “Cassius Clay (also known as Muhammad Ali)” and then “Cassius” or “Clay” throughout. That was apparently the last straw for Times editors. In Daley’s column two days later, the attribution flipped, and it was “Muhammad Ali, also known as Cassius Clay,” and “Ali” thereafter.

As Bryan Curtis writes at the Ringer, Ali dragged some of the more retrograde sports writers into the modern age. But Daley never fully changed, on Ali’s name or his person. Long after the issue was resolved both in the public mind and in the pages of the Times, Daley still dropped in references to “the former Cassius Clay.” In April 1973, a week after Ken Norton broke Ali’s jaw, Daley recycled the bit about 1960 and Rome and the spell cast on him by the young and deferential boxer. “I knew him then as Cassius Clay and still think of him that way.” And as he’d done a decade earlier, Daley stubbornly asserted that Ali didn’t stand a chance. “If the former heavyweight champion of the world is not already gone, it’s obvious that he is on the way,” the Timesman wrote.

Ali would win 15 more fights after Daley declared him close to gone, among them a unanimous decision against Joe Frazier in Madison Square Garden on Jan. 28, 1974. Daley, who’d died earlier that month, didn’t live to see it, depriving him of one last chance to tell New York Times readers that Ali wasn’t nearly as spectacular as he looked.