On March 6, 1964, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad announced that the new heavyweight champion of the world would no longer be known as Cassius Clay. “This Clay name has no meaning,” he said in a radio address. “Muhammad Ali is what I will give him as long as he believes in Allah and follows me.” On March 24, the New York Times’ Robert Lipsyte wrote that Ali “savored his new name.” American newspapers did not. “Clay Rejects $750,000 to Take on Patterson,” was the headline of an NYT story on March 9, 1964. “Clay Defended by Boxing Groups,” said the Los Angeles Times on March 24.

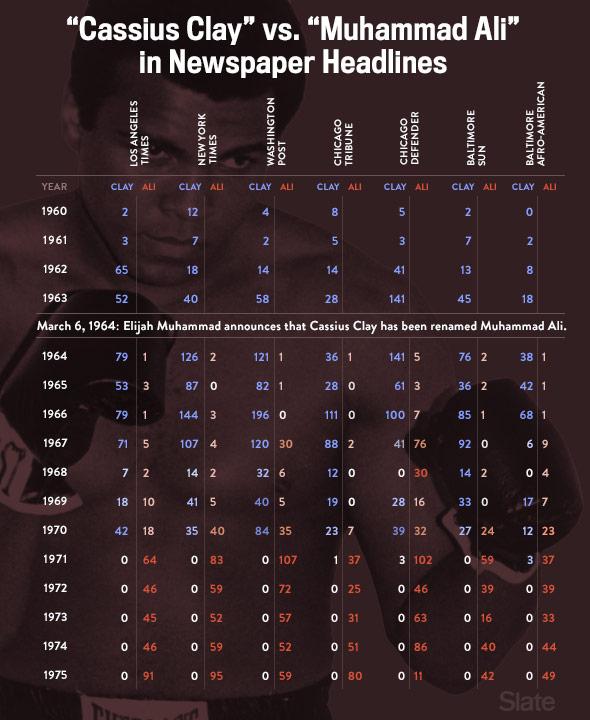

As the New York Times’ Victor Mather reported this week, the newspaper of record was very slow to respect Ali’s new name of record. “From 1964 to 1968, Cassius Clay appeared in more than 1,000 articles, Muhammad Ali in about 150,” Mather wrote.

But it wasn’t just the New York Times that was slow to embrace the champ’s new name. I searched the news database ProQuest for mentions of “Cassius Clay” and “Muhammad Ali” in seven different newspapers: the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Chicago Defender, Baltimore Sun, and Baltimore Afro-American. To get a handle on institutional policy, I counted up how often each paper used “Clay” and “Ali” in headlines. In 1964, those seven papers ran 617 items with “Clay” in the headline compared to 13 for “Ali.” In 1965, when Ali knocked out Sonny Liston in a rematch and then defended his heavyweight title against Floyd Patterson, it was 389 mentions for “Clay” and 10 for “Ali.” In 1966, the NYT reported that Ali “balked at accepting the plaque” for a fighter of the year award because it bore the name Cassius Clay. That year, it was 783 “Clay” vs. 13 “Ali.”

As the table below illustrates, it wasn’t until 1970, six years after the boxer introduced himself as Muhammad Ali, that most newspapers started heeding his wishes. And it wasn’t until 1971 that the tide turned completely.

Chart by Slate

As the graphic demonstrates, the two black newspapers in our data set—the Chicago Defender and Baltimore Afro-American—were slightly quicker to act, but even they continued to tilt toward using “Clay” into the late 1960s.

Why didn’t the newspapers want to call Muhammad Ali “Muhammad Ali”? “Troglodyte editor Abe Rosenthal was emphatic about it being ‘Cassius Clay’ until he changed his name in a court of law,” Lipsyte said to Stefan Fatsis in a story published in Slate earlier this week. Lipsyte told the Times’ Mather that he “found it very embarrassing. We did not ask what John Wayne and Rock Hudson’s real names were.”

At most of the newspapers I looked at, the house style seems to have flipped around the time of Ali’s Oct. 26, 1970, match-up against Jerry Quarry—his first fight back after a 3½-year absence from the ring due to his conscientious objection to the Vietnam War.

New York Times, Sept. 18, 1970: “State Will Grant Clay Ring License”

New York Times, Oct. 24, 1970: “Quarry’s Fight Plan Calls for Outslugging Ali”

Los Angeles Times, Oct. 23, 1970: “It’s Like Old Times for Cassius: Not Just Quarry, I’ve Got to Beat Critics, Too—Clay”

Los Angeles Times, Oct. 28, 1970: “Caller Threatens to Bomb Ali Home”

Washington Post, Oct. 23, 1970: “Clay Injects Race Issue, Quarry Says”

Washington Post, Oct. 30, 1970: “Ali’s Next Bout Is About Set for Dec. 8 with Bonavena”

Chicago Tribune, Oct. 27, 1970: “Clay Stops Quarry in Third Round!”

Chicago Tribune, Dec. 7, 1970: “Ali Says Last Tuneup Will Go Nine Rounds”

The shift in the newspapers’ naming conventions wasn’t always consistent—they would occasionally backslide, using “Clay” rather than “Ali” even after they’d started to change their styles—but the pattern was clear. The nation’s feelings about the Vietnam War had changed, and Muhammad Ali, the boxing champion with the Muslim name, was an American hero again. “I don’t remember a real fiat from on high,” Lipsyte told the Times this week. “I think it was slippage. The older desk guys go and the younger desk guys come in.”

There was a fiat on high from the Associated Press. The Nov. 23–Nov. 29, 1970, edition of the AP Log—a weekly memo distributed to the wire service’s staffers and member publications—explained:

The AP Log then quoted general sports editor Bob Johnson, who said, “Our decision was based on the old news rule that a person is entitled to decide for himself what he is to be called.” The item added that the AP would “put into occasional stories the explanation that Ali originally was known as Cassius Clay, but the probability appears to be that if he sticks to his choice the Clay identity will be dropped except in long background pieces.”

Ali did stick to his choice—he’d already stuck to it for more than six years by that point, not that the AP, the New York Times, or any other major print media entity had seemed to care. But the newspapers changed their ways after the Quarry fight. In 1971, the seven newspapers in our survey used “Clay” in four headlines and “Ali” in 489. By 1972, the name Cassius Clay had been scrubbed from the headlines entirely.*

Ali’s long wait for proper identification would not be replicated when Lew Alcindor changed his name to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar in 1971. On June 6 of that year, the Los Angeles Times featured a morning brief headlined “Lew Alcindor Takes Islamic Name—Call Him Kareem Abdul Jabbar.” The other newspapers were quick to make the switch as well, dropping Alcindor from headlines. Starting in 1972, the New York Times never again called him Alcindor in a headline. If Muhammad Ali hadn’t paved the way with the nation’s sports editors, he likely would’ve had a much longer wait.

*Update, June 10, 2016, 5 p.m.: This piece has been updated with new information about the Associated Press’ policy on Muhammad Ali’s name.