Stefan Fatsis told a version of this story on this week’s edition of Slate’s sports podcast Hang Up and Listen. An adapted transcript of the audio recording is below, and you can listen to Fatsis’ essay by clicking on the player beneath this paragraph and fast-forwarding to the 55:22 mark.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” is one of the young Muhammad Ali’s signature lines. It helped to define him, his opposition to the war in Vietnam, his support for civil rights, and, really, the entire decade of the 1960s. It is arguably one of the most powerful sentences ever spoken by an athlete. It’s emblazoned on a T-shirt.

Through the years, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” has been paired with another unforgettable, unmistakable Ali quote, cited in essays and books and op-eds, and repeated in the obituaries and tributes that have flowed like tap water since the heavyweight champion’s death: “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

But Ali didn’t say “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger” when he first said “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” or something close to it, on Feb. 17, 1966. In fact, he may not have said it at all outside of a movie set. And there’s no evidence he coined the lacerating phrase himself.

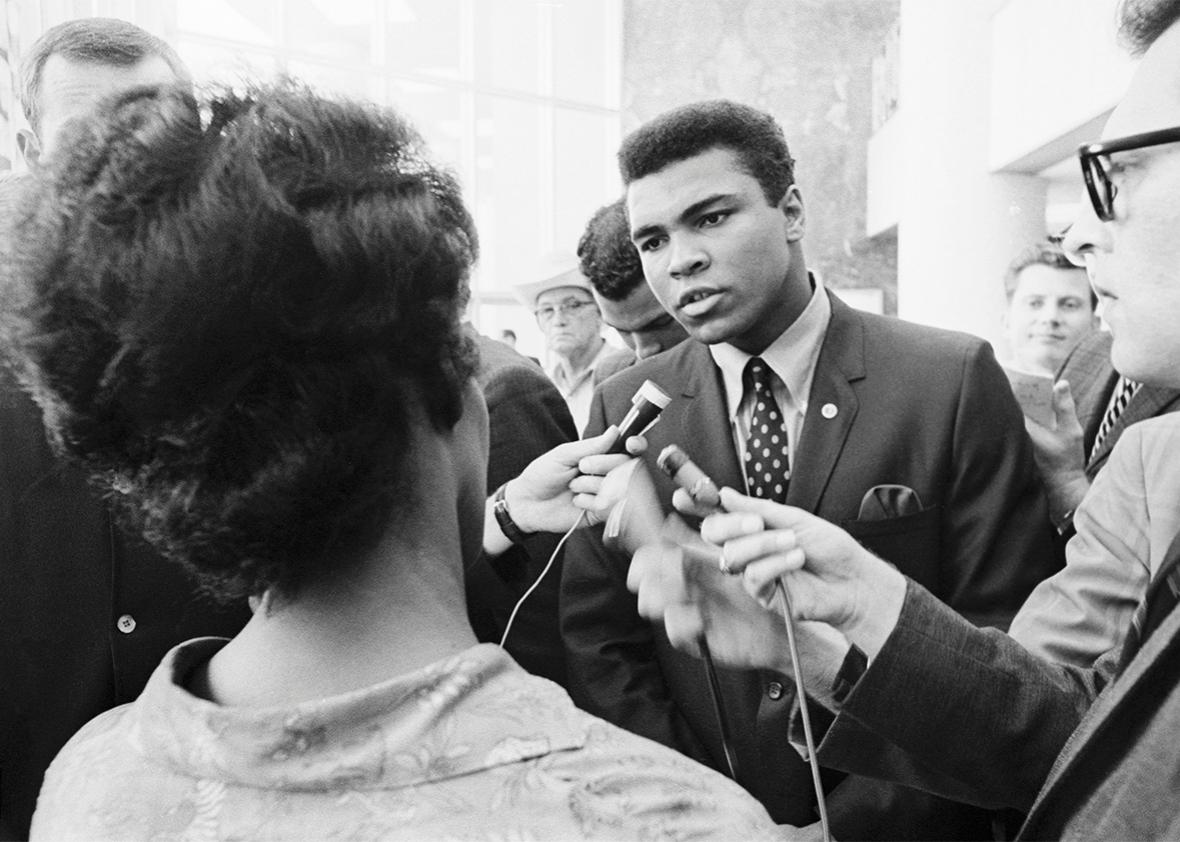

Let’s start with the first sentence, the one Ali did speak. Ali was in Miami, training for a fight against Ernie Terrell. After his early afternoon workouts, he would sit in a lawn chair outside his gray cement rental and chat up high school girls as they walked home. Nation of Islam members attended to him, and reporters hung around him. On that February day in 1966, a reporter told Ali that the draft board in his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, had reclassified him from 1-Y, or unfit for military service, to 1-A, making him immediately eligible to be drafted.

According to Robert Lipsyte, who was at the house reporting a feature for the New York Times, the boxer’s immediate response was more selfishly personal than defiantly political. “Why me?” Lipsyte quoted Ali as saying in the Times the next day. “I can’t understand it. How did they do this to me—the heavyweight champion of the world?” As the news spread, reporters arrived in waves, and neighbors and passers-by did too, asking question after question, for hours.

Ali answered them all. He said, “How can they do this without another test to see if I’m any wiser or worser than the last time?” (Ali in 1964 twice failed an Army pre-induction mental aptitude test.) He wondered why the U.S. government was “gunning” for him. He suggested that officials were biased against his Muslim faith. “I’m fighting for the government every day,” Ali said. “I think it costs them $12 million a day to stay in Vietnam and I buy a lot of bullets, at least three jet bombers a year, and pay the salary of 50,000 fighting men with the money they take from me after my fights.”

“He eventually subsided,” Lipsyte wrote in a May 1967 profile in the New York Times Magazine, “and questioners pressed, asking Ali about Vietnam. He admitted that he wasn’t sure where Vietnam was. They asked him about the Vietcong. He shrugged. ‘I got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’ ”

Lipsyte didn’t include the quotation in his deadline story; spoken half-heartedly by a weary Ali after all those hours of talking, it didn’t instantly resonate. (Lipsyte has said he just blew it.) But the quote, or a version of it, was picked up by other reporters. “I am a member of the Black Muslims, and we don’t go to no wars unless they’re declared by Allah himself,” the Associated Press quoted Ali as saying. “I don’t have no personal quarrel with those Vietcongs.’ ” In an AP dispatch a week later, it was “Vietcong” singular.

Ali’s remarks had an instant impact. The governor of Illinois denounced them as “unpatriotic.” The state’s athletic commission ordered a hearing to discuss barring Ali from fighting Terrell the next month in Chicago; Ali appeared at that hearing and refused to apologize, and the bout was called off. (Ali would defeat Terrell that November in Houston’s Astrodome in what became known as the “What’s My Name Fight.”)

Ali realized the line had force: It was simple and direct, pointed and rebellious, colorful and colloquial. According to Dave Zirin’s book What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States, Ali was asked about his anti-war rhetoric at a press conference later that year. “Keep asking me, no matter how long,” he replied in verse. “On the war in Vietnam, I sing this song. I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong.”

“No Viet Cong ever called me nigger,” however, did not emerge from the Louisville Lip. When Ali received the news about his draft status, the phrase was already circulating in the counterculture. On Feb. 23, 1966, just six days after Ali’s comments in Miami, the Times reported on an anti-war protest in New York where “One Negro demonstrator carried a sign that said ‘The Viet Cong Never Called Me Nigger.’ ” A protester at the March Against Fear in Mississippi that June wore a placard reading “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.” The Times spotted a teenage girl in Chicago that summer wearing “a button pinned to her flowered blouse that said, ‘The Vietcong never called me a nigger,’ ” and United Press International saw a button in Cleveland “on the lapel of a leader of J.F.K. House, a militant youth center.”

The phrase had staying power. In April 1967, at an anti-war march in New York attended by more than 100,000 people, the Times described a sign reading “No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger,” and the Washington Post heard black protesters shouting the phrase. In April 1969, students at historically black Voorhees College in South Carolina put up anti-war posters featuring the line. In his 1998 memoir Walking With the Wind, civil rights leader John Lewis, who headed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the mid-1960s, recalled that “No Vietnamese Ever Called Me Nigger” was “an extremely popular poster” that hung on walls at black colleges and organizations. “We had a copy mounted on the wall of our SNCC headquarters in Atlanta,” Lewis wrote.

So who coined the phrase? It’s not clear. Sociologist Charles Lemert, author of the 2003 book Muhammad Ali: Trickster in the Culture of Irony, has written that the words “were first uncovered in Vietcong propaganda spread among the mostly black ground troops in the Mekong Delta.” In his 2007 book The African American Experience in Vietnam: Brothers in Arms, historian James E. Westheider credited civil rights leader Stokely Carmichael at the 1966 Mississippi March Against Fear: “Why should black folks fight a war against yellow folks so that white folks can keep a land they stole from red folks? We’re not going to Vietnam. Ain’t no Vietcong ever called me nigger!” But that was four months after the sign at the anti-war march in New York.

Regardless of its provenance, Ali received credit for its popularization. The words “would become Muhammad Ali’s calling card,” Peniel E. Joseph wrote in his 2014 biography, Stokely: A Life. “For Ali, still searching for a way to articulate a viewpoint that he had instinctively understood when he blurted out his own Vietcong remark, Carmichael’s phrase resonated,” Howard L. Bingham and Max Wallace wrote in their 2000 book Muhammad Ali’s Greatest Fight: Cassius Clay vs. the United States of America. “From then on, he often told crowds and reporters, ‘No Vietcong ever called me nigger!’ when pressed to explain his anti-war stand.”

That’s a plausible and convenient narrative. But none of the contemporaneous reporting on the phrase attributes it to Ali or otherwise connects it to him, and searches of several publication databases don’t turn up Ali saying those words verbatim, or even nearly so. According to searches on Amazon, the quotation isn’t mentioned at all in Zirin’s book, in David Remnick’s 1998 biography King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, or in Thomas Hauser’s 1992 oral history Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times.

Ali did say something along the lines of the quotation at least a couple of times, though not in a poster-worthy way. Here’s one of those instances, from a 1970 interview with the journal Black Scholar:

I met two black soldiers a while back in an airport. They said: “Champ, it takes a lot of guts to do what you’re doing.” I told them: “Brothers, you just don’t know. If you knew where you were going now, if you knew your chances of coming out with no arm or no eye, fighting those people in their own land, fighting Asian brothers, you got to shoot them, they never lynched you, never called you nigger, never put dogs on you, never shot your leaders. You’ve got to shoot your ‘enemies’ (they call them) and as soon as you get home you won’t be able to find a job. Going to jail for a few years is nothing compared to that.”

Then there’s this, from an interview that appears to have been conducted shortly after Ali refused military induction in April 1967 and was part of a 1980 documentary by the black public affairs television program Like It Is:

My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor, hungry people in the mud, for big, powerful America, and shoot them. For what? They never called me nigger. They never lynched me. They never put no dogs on me. They never robbed me of my nationality, or raped and killed my mother and father. … How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.

Actually, Ali did say the phrase at least once—in The Greatest, a 1977 biopic starring Ali as himself, and featuring Ernest Borgnine as trainer Angelo Dundee and James Earl Jones as Malcolm X. The screenwriters imagined Ali saying the line on that day in Miami when he learned about his draft status. When a reporter asks whether he wants to go fight “the enemy,” Ali replies, “Whose enemy? Man, the Viet Cong never called me no nigger. They your enemy, not mine.”

The 2001 feature film Ali went one step further. In that movie, directed by Michael Mann, Will Smith says the two seminal lines—“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong. Ain’t no Viet Cong ever called me nigger”—back to back, hewing to the popular myth. In this re-enactment, the boxer delivers the lines not in Miami but in a Houston hotel room after he has refused induction, and not out of unthinking exhaustion but with deliberate intent. “Ali perceives it intuitively and reflexively,” the script direction reads.

It’s possible that at some point Ali did utter the famous sentences in order and unscripted in precisely the way they are rendered, as so many accounts claim he did. He talked a lot, after all. Ultimately, though, whether Ali did or didn’t doesn’t really matter. “The survival of the quotation helps insure the survival of the person to whom it is misattributed,” Louis Menand wrote in the New Yorker in 2007, citing Ali and others who didn’t say the famous things they are said to have said. What matters is that Ali recognized the symbolic might of his off-the-cuff words and used them to define his own political character—and to influence the culture, in the moment and, now, beyond his death. Like his fists, Ali’s words could be devastating, even when he didn’t say them.